One of the essential factors for widespread robotics adoption, especially in the inspection and maintenance area, is the regulatory landscape. Regulatory and legal issues should be addressed to establish effective robotics deployment legal frameworks. Common goals of boosting the widespread adoption of robotics can only be achieved by creating networks between the robotics community and regulators.

On the 23rd of March, Maarit Sandelin, Peter Voorhans and Dr Carlos Cuevas Garcia were invited by Robotics4EU and RIMA network to discuss how cooperation among regulators and the robotics community can be fostered and what are the most pressing legal challenges for the inspection & maintenance application area of robotics.

Maarit Sandelin and Peter Voorhans from Robotic Innovation Department in SPRINT Robotics have opened the workshop with the question of why robotics are important in inspection and maintenance? Speakers highlighted three main aspects: safety, efficiency and costs. Firstly, robotic solutions allow for reducing the fatalities and risks of accidents in the environments of heights, confined spaces or under-water. Secondly, the preparation work for inspection and maintenance (shutting down the facilities, clearing and cleaning the spaces, air sampling, getting the permits) is not required for inspection and maintenance done by a robot. The bureaucracy – applying and waiting for permits – is reduced as well.

However, the integration of robots faces barriers in two main dimensions: differences in cross-border standards and acceptance of robotics by inspectors. Speaking of regulatory challenges, Peter Voorhans identified the main problems:

- The regulatory framework for acceptance in robotics is disastrous at the global level

- Robotic inspections are not always allowed based on regulations or interpretation of the regulation

- A different interpretation of regulations causes issues for service and technical providers

To move further with the integration of robots into Inspection and maintenance, the Europe-wide acceptance and legislation of robots are needed. First, the acceptance of robotics (for example, remote visual techniques) by notified bodies would be a big step further. Also, the training of inspectors should involve robotics training, so the inspectors would understand the advantages and consequences of the integration of robotics and could advocate themselves for the uptake of robotics.

Different legislation and regulations across borders mean that in each country, inspection has to be performed by local certified inspectors. For example, a Dutch company is performing an in-service inspection in France. Due to differences in legislation, a certified inspector from the Netherlands is not allowed to perform the remote visual inspection in France. A local notified body needs to be involved.

Leaving aside the national & cross-border legislation issues, Peter Voornhans has drawn attention to the company-level of policies. As an example, the internal policies in DOW, chemical and plastics manufacturer, defined that people will not be allowed in confined spaces starting from 2025. This leadership position gave a strong incentive to introduce robotics and convince inspectors to use them. The internal programme ensured the recognition and celebration of robotic use cases and best practices, ensuring higher levels of robotics acceptance overall.

Dr Carlos Cuevas Garcia, a postdoctoral researcher at the Innovation, Society and Public Policy Research Group at the Munich Center for Technology in Society (MCTS), Technical University Munich, has shared his experience in following the EU-funded projects for uptake of robotics in I&M. Dr Garcia has evaluated the policy goals and results, following the cycle of the projects, as policy instruments.

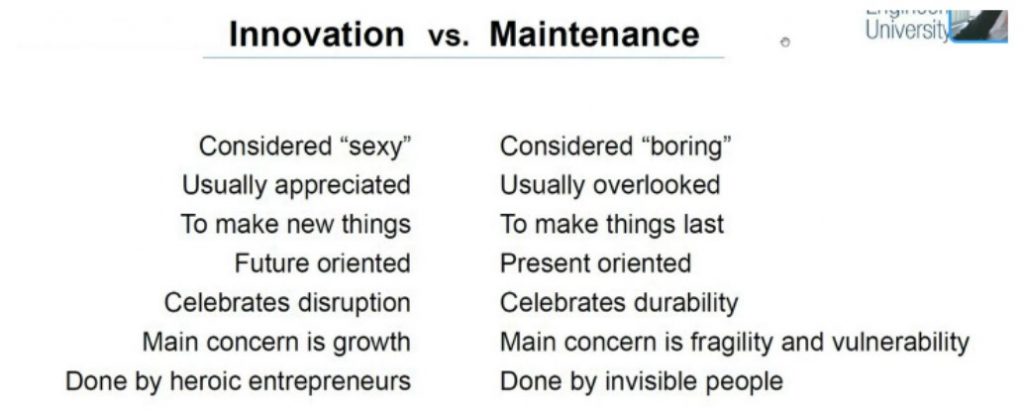

From the sociology of technology perspective, robotics in I&M plays at the unique intersection of innovation and maintenance. Innovation is done by heroic people, entrepreneurs, it is celebrated, and covered in news. Maintenance is done by invisible people, it is usually overlooked. However, such projects as RIMA, bring the two dimensions together. As innovation aims at improving maintenance, what can innovation learn from maintenance? How can maintenance improve innovation?

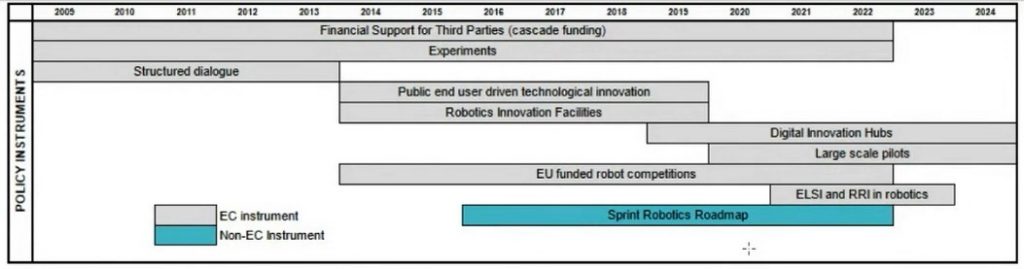

Speaking of the policy role in this intersection, Dr Garcia has presented the innovation policy landscape from the instrument’s perspective.

In order to improve this landscape, he identified two ways forward:

- Examine the effects of individual policy instruments on the field of I&M robotics

- Examine the dynamics of different instruments together, and how they enable (and constrain!) the continuity of projects

The examination could be implemented considering the vulnerabilities in the policy instruments. Drawing from the experience in observing and analysing the EU-funded projects, as instruments to achieve policy goals, Carlos identified several vulnerabilities:

- The confusion between the role of the “public end-user” and the role of the subcontractor. In the case of the observed projects, the subcontractors’ input was not formally involved, even though the maintenance is actually done by the subcontractor.

- The interest of the “public end-user” and subcontractor to purchase or keep funding the technologies of the solution after the project was not sufficient

- The “public end-user” didn’t want to directly fund a technology considered risky for workers’ jobs.

- The particular policy instrument observed (Public end user-Driven Technological Innovation) was too rigid to respond to the complexities of the situation, yet too weak to provide further directions

.

Speaking of ways to improve the policy process, Carlos identified that besides technical progress (for example, going beyond technological readiness level from 2 to 5), instruments should consider other metrics of success, e.g.:

- How well do roboticists’ teams and maintainers work together?

- How do robots empower maintainers?

- How does the team co-create a vision of the whole inspection process (service logistics, transporting, unloading, fixing robots, etc.)?

Dr Carlos concluded by suggesting a couple of policy recommendations:

- We must explore the learning trajectories of different types of stakeholders involved in sequences of I&M robotics projects;

- We have to learn how to provide maintenance to innovation networks and repair innovation policy instruments by better identifying their contradictions, fragilities and vulnerabilities;

- This requires close and durable engagement between I&M experts, roboticists, project coordinators, policymakers, regulators, and sociologists of technology.

Finally, the session was concluded with a panel discussion thematizing previous presentations, and engaging the audience. As a final conclusion, the experts suggested beginning with industry-led insights to change the paradigm of policy framework on a larger scale.