What’s in Store for the 2022 RoboBusiness Conference and the Field Robotics Engineering Forum?

My journey from DeepMind intern to mentor

My journey from DeepMind intern to mentor

How are everyday scientific practices influenced by automation and digitalization?

Eagle-Eyed Computers: Machine Vision and Optical Components

A soft, fatigue-free and self-healing artificial ionic skin

IMTS 2022 Product Preview

MiGriBot: a miniature robot able to perform pick-and-place operations of sub-millimeter objects

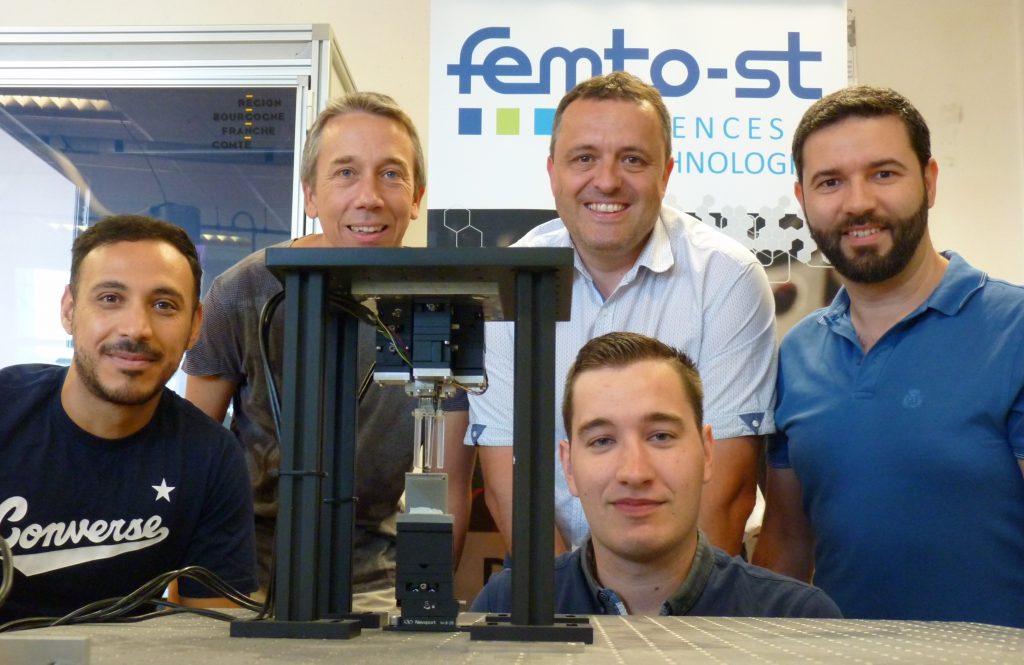

Research team : Maxence LEVEZIEL, Wissem HAOUAS, Michaël GAUTHIER, Guillaume J. LAURENT, Redwan DAHMOUCHE.

By Redwan Dahmouche

Speed and precision are two major issues in robotics and in Industry of the Future (also known as Industry 4.0). Within this framework, RoMoCo research team of AS2M department at FEMTO-ST Institute has developed MiGriBot, a miniature robot able to perform 720 pick-and-place operations of sub-millimeter objects per minute. The results of this research work have been published in Science Robotics.

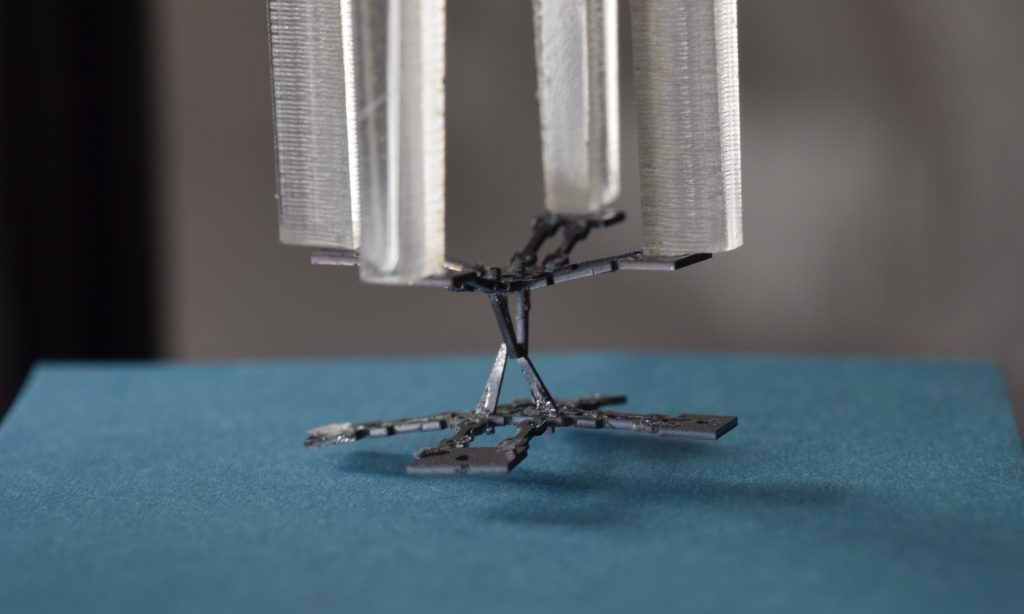

These performances are made possible thanks to its architecture, that allows it to grip and manipulate micro-objects barely visible to the naked eye (from 40 micrometers to several hundred micrometers). In fact, where other microrobots have a rigid end-effector, MiGriBot is based on a principle with an articulated end. This articulated end allows to drive a microgripper without any wire or embedded actuator. The second advantage of this robot is that all its degrees of mobility, including the ones from the microgripper on the articulated end, are operated from the base of the robot, making its mobile parts very lightweight. Finally, its robotic structure occupies a surface of only 20x20mm2. This level of compactness is achieved by using Silicon for the rigid elements, a polymer (Polydimethylsiloxane – PDMS) as flexible joints and piezoelectric actuators equipped with position sensors. MiGriBot is therefore lighter, more compact and faster than existing robotic micro-manipulators.

MiGriBot holding a cylindrical ruby with a diameter of 700µm and a thickness of 200µm.

While the fastest industrial pick-and-place robots do not exceed 250 cycles per minute, the combination of all the features of this robot: soft joints, small footprint, integrated gripping, lightweight structure and closed-loop control of the fast actuators allows MiGriBot to reach 720 pick-and-place operations per minute with about one micrometer accuracy. In the blink of an eye, MiGRiBot will have manipulated 5 micro-objects, which means that it will have approached, grabbed, moved and released an object 5 times successively.

This robot will be used to assemble Micro-Electro-Mechanical and Optical Systems (MEMS/MOEMS) used in the electronics industry, where the production throughput is increasingly high. Thanks to its speed and compactness, more than 2000 robots can be placed in 1m2 to perform more than one million operations per second. Increasing work rates will improve the productivity and competitiveness of manufacturers, which may encourage the relocation of production to Europe, America and countries with high labor costs. Applications in watch industry, medical instrumentation, aerospace, and other fields are also possible.

MiGriBot holding another parallel structure showing the capacity of the microrobot to manipulate heavy objects.

This work was funded by the ANR MiniSoRo project (ANR-19-CE10-0004) and by Grand Besançon Métropole.

Research team: Maxence LEVEZIEL, Wissem HAOUAS, Michaël GAUTHIER, Guillaume J. LAURENT, Redwan DAHMOUCHE (associate professor at université de Franche-Comté, project leader and head of the research team: redwan.dahmouche@univ-fcomte.fr / 06 29 24 19 81).