Knight Optical – Custom-Made Optical Components for High-Performing Automation Systems

A new approach for safer control of mobile robotic arms

Achieving End-to-end Automation With Autonomous Machine Vision

Unable to attend #ICRA2022 for accessibility issues? Or just curious to see robots?

We can now offer you a telepresence robot tour of the ICRA 2022 expo hall, competitions and poster sessions, thanks to generous support from our friends at OhmniLabs. OhmniLabs build human-centric robots that elevate quality of life for billions of people worldwide, and they build all the robots right here in Silicon Valley using advanced additive manufacturing.

Join more than 5000 roboticists, researchers and industry from 89 different countries in Pennsylvania for a fascinating showcase of robotics thought leadership. There will be 12 keynote speakers, 6 industry and entrepreneurial forums, 10 competitions, almost 60 workshops and 1500 papers presented. And on top of that there are more than 80 robotics companies demoing their technologies, ranging from Agility Robotics to Zebra Technologies/Fetch Robotics.

There are many things that can make it difficult to attend an in person conference in the United States and so the ICRA Organizing Committee, the IEEE Robotics and Automation Society and OhmniLabs would like to help you attend ICRA virtually. Priority of access will be for robotics researchers and students who are unable to travel, particularly if you are an author of a paper or poster, but we welcome applications from people who are simply curious about robots as well.

Three OhmniBots will be in the main exhibition hall (with all the other robots) from opening to closing on Tuesday May 24th, Wednesday May 25th and Thursday May 26th, with time slots aligning with Poster Sessions, networking breaks and Expo Hall hours. The application form allows you to select several time slots, and we’ll give you feedback as soon as possible about your application, but we won’t be able to confirm your final booking time(s) until Monday May 23.

Telepresence Robot access is also available for media tours, ICRA sponsors, and members of Black in Robotics, Women in Robotics or Open Robotics who’d like to join the networking events. Generally, the robots are limited to the Expo Floor but we might be able to make special arrangements

Contact one of the Accessibility Chairs: AndraKeay@ieee.org with subject [telepresence tour]

Or one of the Media Chairs: danicarzap@scientificagitation.com with subject [media]

Let us know why you need to tour ICRA by telepresence robot!

Duckietown Competition Spotlight

At ICRA 2022, Competitions are a core part of the conference. We shine a spotlight on influential competitions in Robotics. In this episode, Dr Liam Paull talks about the Duckietown Competition, where robots drive around Rubber Ducky passengers in an autonomous driving track.

Dr. Liam Paull

Liam Paull is an assistant professor at l’Université de Montréal and the head of the Montreal Robotics and Embodied AI Lab (REAL). His lab focuses on robotics problems including building representations of the world (such as for simultaneous localization and mapping), modeling of uncertainty, and building better workflows to teach robotic agents new tasks (such as through simulation or demonstration). Previous to this, Liam was a research scientist at CSAIL MIT where he led the TRI funded autonomous car project. He was also a postdoc in the marine robotics lab at MIT where he worked on SLAM for underwater robots. He obtained his PhD from the University of New Brunswick in 2013 where he worked on robust and adaptive planning for underwater vehicles. He is a co-founder and director of the Duckietown Foundation, which is dedicated to making engaging robotics learning experiences accessible to everyone. The Duckietown class was originally taught at MIT but now the platform is used at numerous institutions worldwide.

Links

- Download mp3 (20.1 MB)

- Subscribe to Robohub using iTunes, RSS, or Spotify

- Support us on Patreon

Artificial muscles help robot vacuum manipulators get a grip

A beaver-inspired method to guide the movements of a one-legged swimming robot

Tiny drone based on maple seed pod doubles flight time

Tote-To-Person AMR – a market and technology study from Interact Analysis & Geek+

Emergent Bartering Behaviour in Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning

Designing societally beneficial Reinforcement Learning (RL) systems

By Nathan Lambert, Aaron Snoswell, Sarah Dean, Thomas Krendl Gilbert, and Tom Zick

Deep reinforcement learning (DRL) is transitioning from a research field focused on game playing to a technology with real-world applications. Notable examples include DeepMind’s work on controlling a nuclear reactor or on improving Youtube video compression, or Tesla attempting to use a method inspired by MuZero for autonomous vehicle behavior planning. But the exciting potential for real world applications of RL should also come with a healthy dose of caution – for example RL policies are well known to be vulnerable to exploitation, and methods for safe and robust policy development are an active area of research.

At the same time as the emergence of powerful RL systems in the real world, the public and researchers are expressing an increased appetite for fair, aligned, and safe machine learning systems. The focus of these research efforts to date has been to account for shortcomings of datasets or supervised learning practices that can harm individuals. However the unique ability of RL systems to leverage temporal feedback in learning complicates the types of risks and safety concerns that can arise.

This post expands on our recent whitepaper and research paper, where we aim to illustrate the different modalities harms can take when augmented with the temporal axis of RL. To combat these novel societal risks, we also propose a new kind of documentation for dynamic Machine Learning systems which aims to assess and monitor these risks both before and after deployment.

What’s Special About RL? A Taxonomy of Feedback

Reinforcement learning systems are often spotlighted for their ability to act in an environment, rather than passively make predictions. Other supervised machine learning systems, such as computer vision, consume data and return a prediction that can be used by some decision making rule. In contrast, the appeal of RL is in its ability to not only (a) directly model the impact of actions, but also to (b) improve policy performance automatically. These key properties of acting upon an environment, and learning within that environment can be understood as by considering the different types of feedback that come into play when an RL agent acts within an environment. We classify these feedback forms in a taxonomy of (1) Control, (2) Behavioral, and (3) Exogenous feedback. The first two notions of feedback, Control and Behavioral, are directly within the formal mathematical definition of an RL agent while Exogenous feedback is induced as the agent interacts with the broader world.

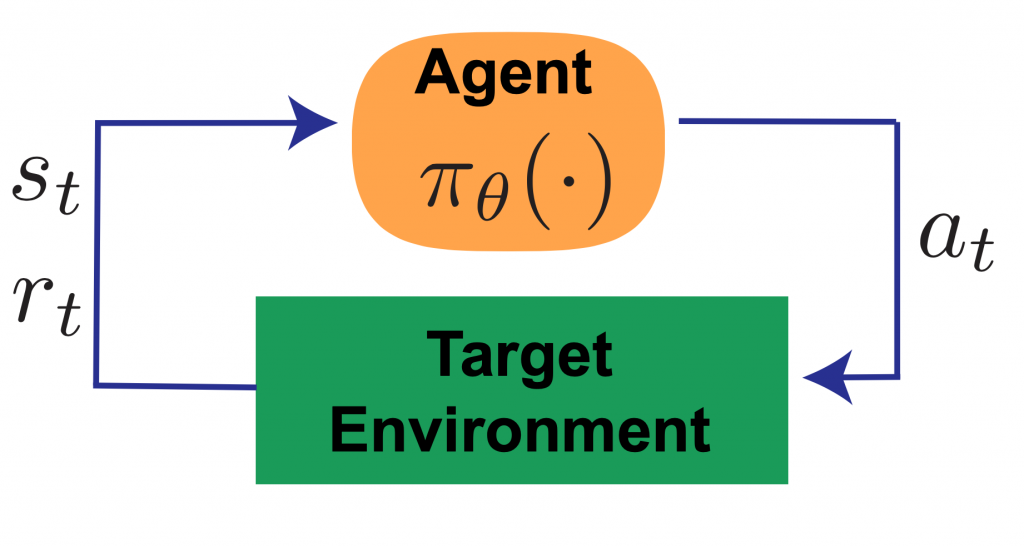

1. Control Feedback

First is control feedback – in the control systems engineering sense – where the action taken depends on the current measurements of the state of the system. RL agents choose actions based on an observed state according to a policy, which generates environmental feedback. For example, a thermostat turns on a furnace according to the current temperature measurement. Control feedback gives an agent the ability to react to unforeseen events (e.g. a sudden snap of cold weather) autonomously.

Figure 1: Control Feedback.

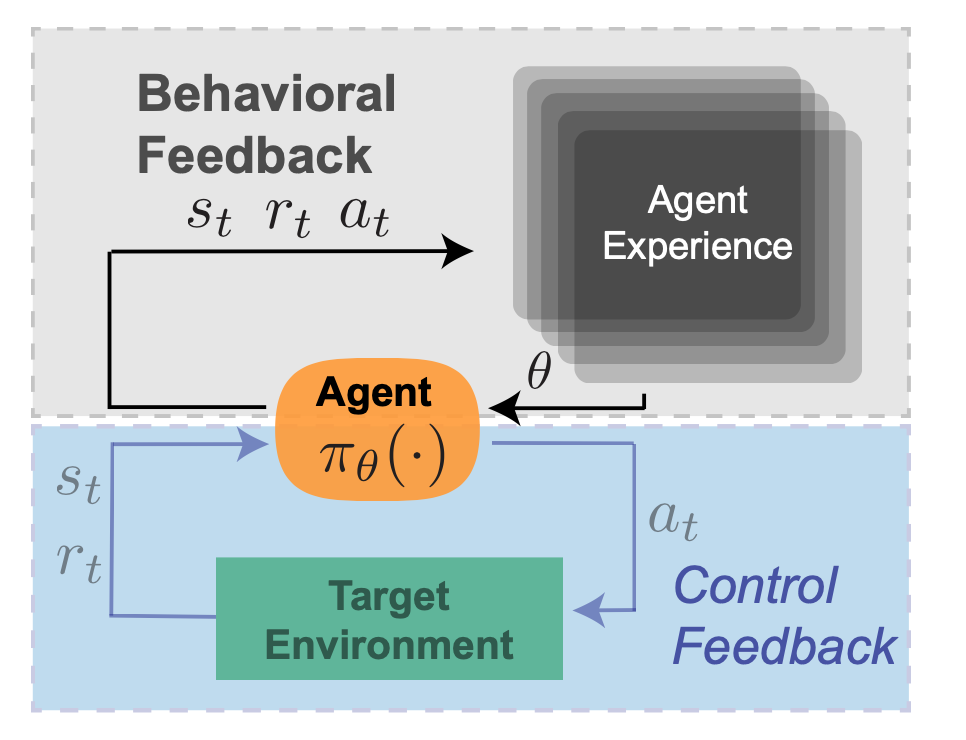

2. Behavioral Feedback

Next in our taxonomy of RL feedback is ‘behavioral feedback’: the trial and error learning that enables an agent to improve its policy through interaction with the environment. This could be considered the defining feature of RL, as compared to e.g. ‘classical’ control theory. Policies in RL can be defined by a set of parameters that determine the actions the agent takes in the future. Because these parameters are updated through behavioral feedback, these are actually a reflection of the data collected from executions of past policy versions. RL agents are not fully ‘memoryless’ in this respect–the current policy depends on stored experience, and impacts newly collected data, which in turn impacts future versions of the agent. To continue the thermostat example – a ‘smart home’ thermostat might analyze historical temperature measurements and adapt its control parameters in accordance with seasonal shifts in temperature, for instance to have a more aggressive control scheme during winter months.

Figure 2: Behavioral Feedback.

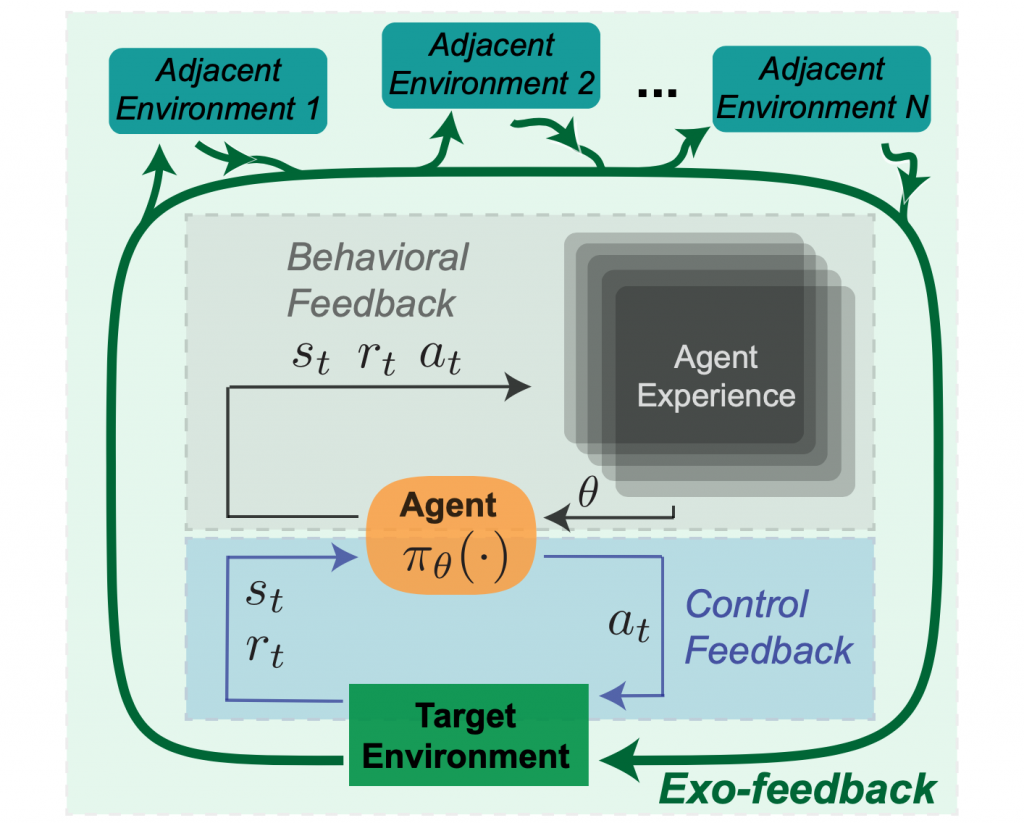

3. Exogenous Feedback

Finally, we can consider a third form of feedback external to the specified RL environment, which we call Exogenous (or ‘exo’) feedback. While RL benchmarking tasks may be static environments, every action in the real world impacts the dynamics of both the target deployment environment, as well as adjacent environments. For example, a news recommendation system that is optimized for clickthrough may change the way editors write headlines towards attention-grabbing clickbait. In this RL formulation, the set of articles to be recommended would be considered part of the environment and expected to remain static, but exposure incentives cause a shift over time.

To continue the thermostat example, as a ‘smart thermostat’ continues to adapt its behavior over time, the behavior of other adjacent systems in a household might change in response – for instance other appliances might consume more electricity due to increased heat levels, which could impact electricity costs. Household occupants might also change their clothing and behavior patterns due to different temperature profiles during the day. In turn, these secondary effects could also influence the temperature which the thermostat monitors, leading to a longer timescale feedback loop.

Negative costs of these external effects will not be specified in the agent-centric reward function, leaving these external environments to be manipulated or exploited. Exo-feedback is by definition difficult for a designer to predict. Instead, we propose that it should be addressed by documenting the evolution of the agent, the targeted environment, and adjacent environments.

Figure 3: Exogenous (exo) Feedback.

How can RL systems fail?

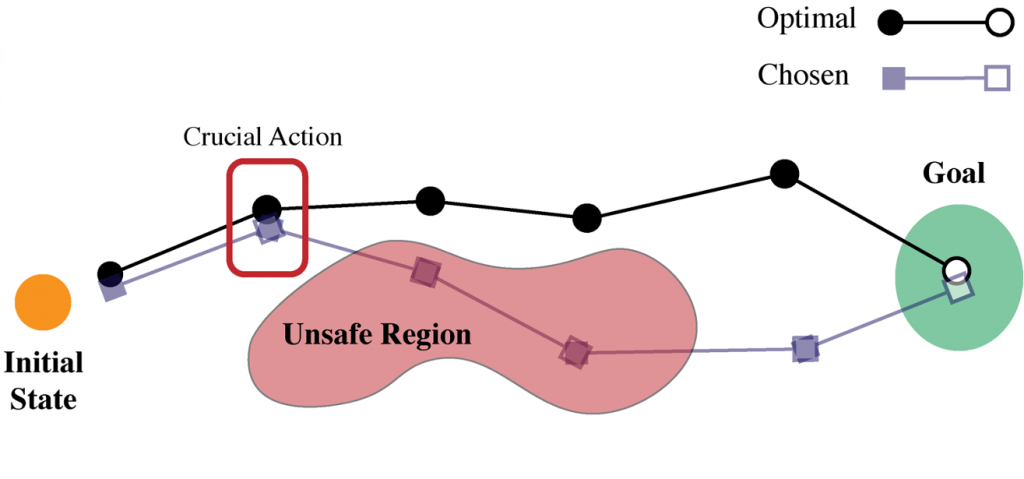

Let’s consider how two key properties can lead to failure modes specific to RL systems: direct action selection (via control feedback) and autonomous data collection (via behavioral feedback).

First is decision-time safety. One current practice in RL research to create safe decisions is to augment the agent’s reward function with a penalty term for certain harmful or undesirable states and actions. For example, in a robotics domain we might penalize certain actions (such as extremely large torques) or state-action tuples (such as carrying a glass of water over sensitive equipment). However it is difficult to anticipate where on a pathway an agent may encounter a crucial action, such that failure would result in an unsafe event. This aspect of how reward functions interact with optimizers is especially problematic for deep learning systems, where numerical guarantees are challenging.

Figure 4: Decision time failure illustration.

As an RL agent collects new data and the policy adapts, there is a complex interplay between current parameters, stored data, and the environment that governs evolution of the system. Changing any one of these three sources of information will change the future behavior of the agent, and moreover these three components are deeply intertwined. This uncertainty makes it difficult to back out the cause of failures or successes.

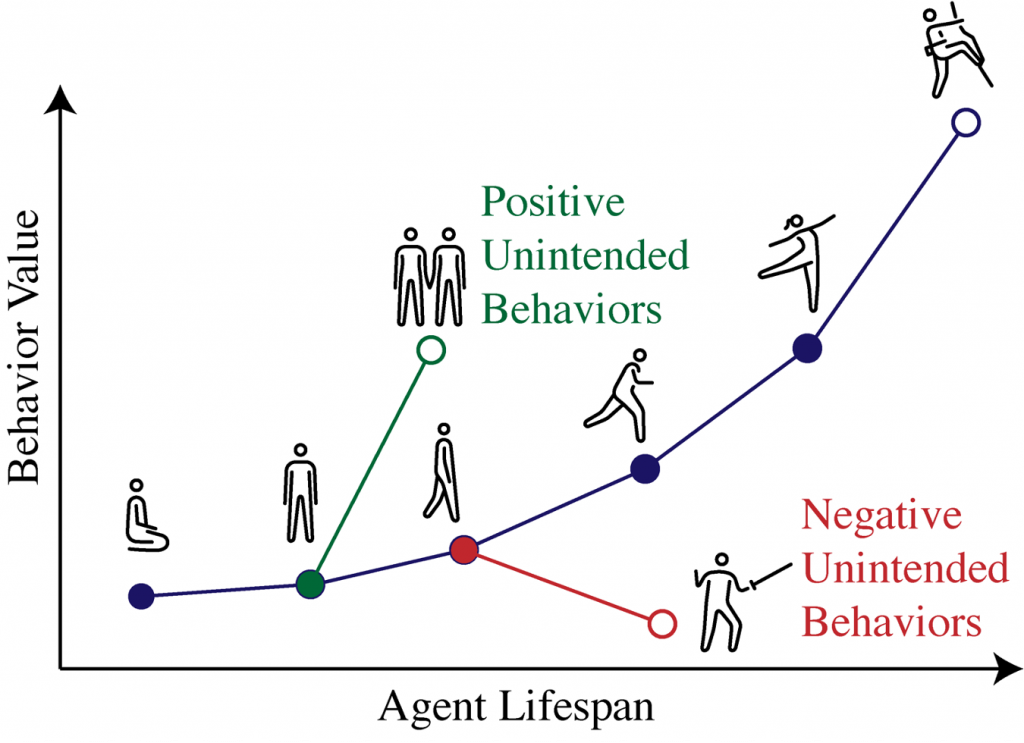

In domains where many behaviors can possibly be expressed, the RL specification leaves a lot of factors constraining behavior unsaid. For a robot learning locomotion over an uneven environment, it would be useful to know what signals in the system indicate it will learn to find an easier route rather than a more complex gait. In complex situations with less well-defined reward functions, these intended or unintended behaviors will encompass a much broader range of capabilities, which may or may not have been accounted for by the designer.

Figure 5: Behavior estimation failure illustration.

While these failure modes are closely related to control and behavioral feedback, Exo-feedback does not map as clearly to one type of error and introduces risks that do not fit into simple categories. Understanding exo-feedback requires that stakeholders in the broader communities (machine learning, application domains, sociology, etc.) work together on real world RL deployments.

Risks with real-world RL

Here, we discuss four types of design choices an RL designer must make, and how these choices can have an impact upon the socio-technical failures that an agent might exhibit once deployed.

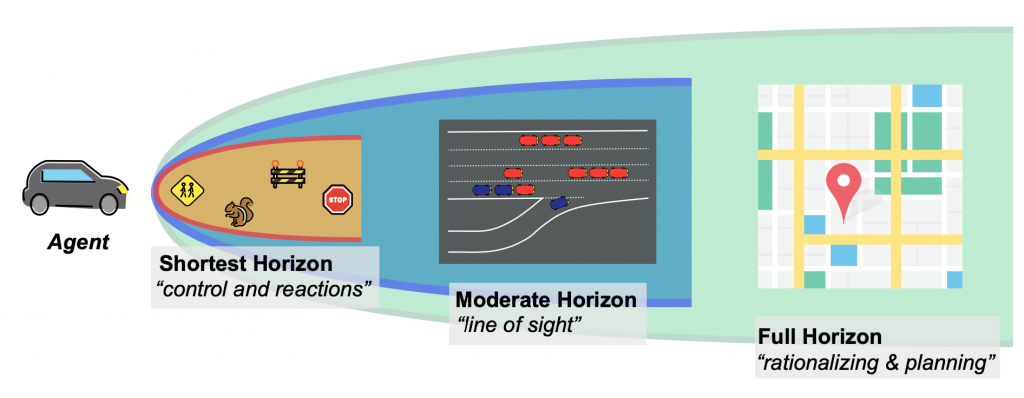

Scoping the Horizon

Determining the timescale on which aRL agent can plan impacts the possible and actual behavior of that agent. In the lab, it may be common to tune the horizon length until the desired behavior is achieved. But in real world systems, optimizations will externalize costs depending on the defined horizon. For example, an RL agent controlling an autonomous vehicle will have very different goals and behaviors if the task is to stay in a lane, navigate a contested intersection, or route across a city to a destination. This is true even if the objective (e.g. “minimize travel time”) remains the same.

Figure 6: Scoping the horizon example with an autonomous vehicle.

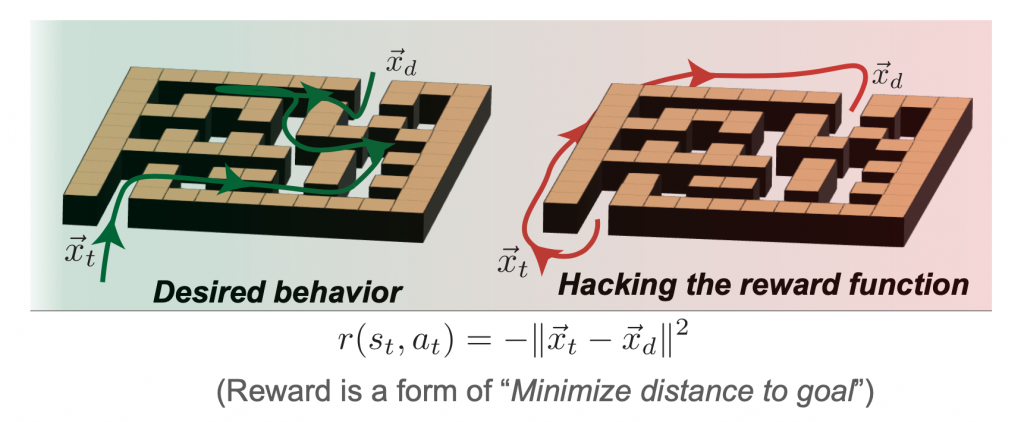

Defining Rewards

A second design choice is that of actually specifying the reward function to be maximized. This immediately raises the well-known risk of RL systems, reward hacking, where the designer and agent negotiate behaviors based on specified reward functions. In a deployed RL system, this often results in unexpected exploitative behavior – from bizarre video game agents to causing errors in robotics simulators. For example, if an agent is presented with the problem of navigating a maze to reach the far side, a mis-specified reward might result in the agent avoiding the task entirely to minimize the time taken.

Figure 7: Defining rewards example with maze navigation.

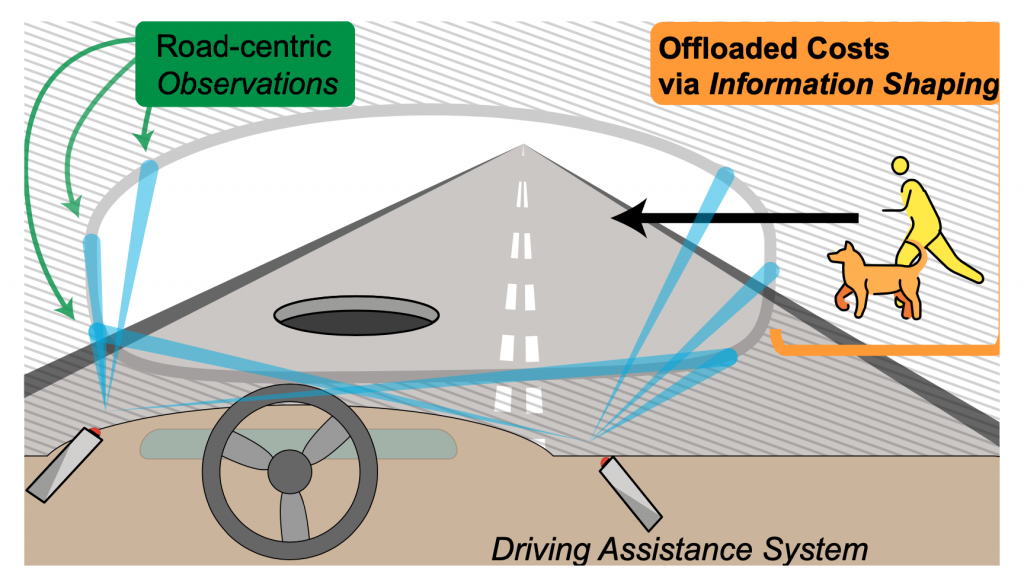

Pruning Information

A common practice in RL research is to redefine the environment to fit one’s needs – RL designers make numerous explicit and implicit assumptions to model tasks in a way that makes them amenable to virtual RL agents. In highly structured domains, such as video games, this can be rather benign.However, in the real world redefining the environment amounts to changing the ways information can flow between the world and the RL agent. This can dramatically change the meaning of the reward function and offload risk to external systems. For example, an autonomous vehicle with sensors focused only on the road surface shifts the burden from AV designers to pedestrians. In this case, the designer is pruning out information about the surrounding environment that is actually crucial to robustly safe integration within society.

Figure 8: Information shaping example with an autonomous vehicle.

Training Multiple Agents

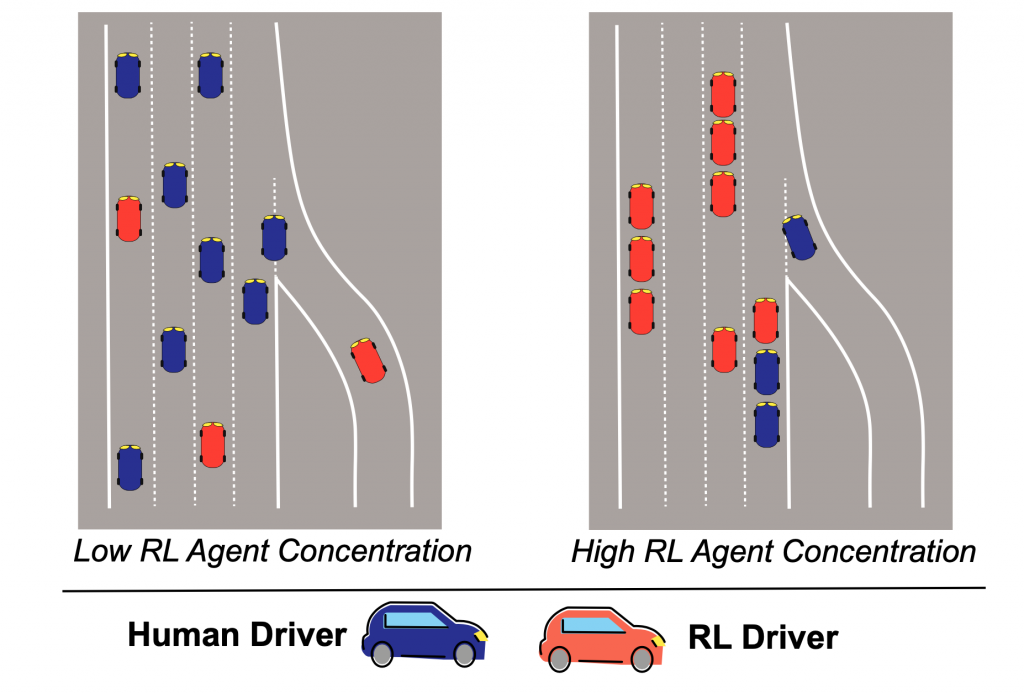

There is growing interest in the problem of multi-agent RL, but as an emerging research area, little is known about how learning systems interact within dynamic environments. When the relative concentration of autonomous agents increases within an environment, the terms these agents optimize for can actually re-wire norms and values encoded in that specific application domain. An example would be the changes in behavior that will come if the majority of vehicles are autonomous and communicating (or not) with each other. In this case, if the agents have autonomy to optimize toward a goal of minimizing transit time (for example), they could crowd out the remaining human drivers and heavily disrupt accepted societal norms of transit.

Figure 9: The risks of multi-agency example on autonomous vehicles.

Making sense of applied RL: Reward Reporting

In our recent whitepaper and research paper, we proposed Reward Reports, a new form of ML documentation that foregrounds the societal risks posed by sequential data-driven optimization systems, whether explicitly constructed as an RL agent or implicitly construed via data-driven optimization and feedback. Building on proposals to document datasets and models, we focus on reward functions: the objective that guides optimization decisions in feedback-laden systems. Reward Reports comprise questions that highlight the promises and risks entailed in defining what is being optimized in an AI system, and are intended as living documents that dissolve the distinction between ex-ante (design) specification and ex-post (after the fact) harm. As a result, Reward Reports provide a framework for ongoing deliberation and accountability before and after a system is deployed.

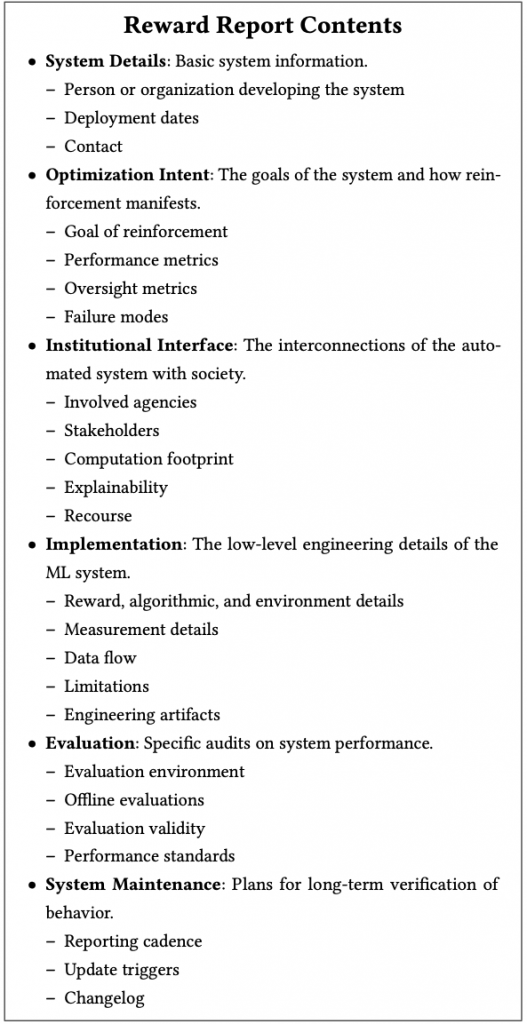

Our proposed template for a Reward Reports consists of several sections, arranged to help the reporter themselves understand and document the system. A Reward Report begins with (1) system details that contain the information context for deploying the model. From there, the report documents (2) the optimization intent, which questions the goals of the system and why RL or ML may be a useful tool. The designer then documents (3) how the system may affect different stakeholders in the institutional interface. The next two sections contain technical details on (4) the system implementation and (5) evaluation. Reward reports conclude with (6) plans for system maintenance as additional system dynamics are uncovered.

The most important feature of a Reward Report is that it allows documentation to evolve over time, in step with the temporal evolution of an online, deployed RL system! This is most evident in the change-log, which is we locate at the end of our Reward Report template:

Figure 10: Reward Reports contents.

What would this look like in practice?

As part of our research, we have developed a reward report LaTeX template, as well as several example reward reports that aim to illustrate the kinds of issues that could be managed by this form of documentation. These examples include the temporal evolution of the MovieLens recommender system, the DeepMind MuZero game playing system, and a hypothetical deployment of an RL autonomous vehicle policy for managing merging traffic, based on the Project Flow simulator.

However, these are just examples that we hope will serve to inspire the RL community–as more RL systems are deployed in real-world applications, we hope the research community will build on our ideas for Reward Reports and refine the specific content that should be included. To this end, we hope that you will join us at our (un)-workshop.

Work with us on Reward Reports: An (Un)Workshop!

We are hosting an “un-workshop” at the upcoming conference on Reinforcement Learning and Decision Making (RLDM) on June 11th from 1:00-5:00pm EST at Brown University, Providence, RI. We call this an un-workshop because we are looking for the attendees to help create the content! We will provide templates, ideas, and discussion as our attendees build out example reports. We are excited to develop the ideas behind Reward Reports with real-world practitioners and cutting-edge researchers.

For more information on the workshop, visit the website or contact the organizers at geese-org@lists.berkeley.edu.

This post is based on the following papers:

- Choices, Risks, and Reward Reports: Charting Public Policy for Reinforcement Learning Systems by Thomas Krendl Gilbert, Sarah Dean, Tom Zick, Nathan Lambert. Center for Long Term Cybersecurity Whitepaper Series 2022.

- Reward Reports for Reinforcement Learning by Thomas Krendl Gilbert, Sarah Dean, Nathan Lambert, Tom Zick and Aaron Snoswell. ArXiv Preprint 2022.

Innovative ‘smart socks’ could help millions living with dementia

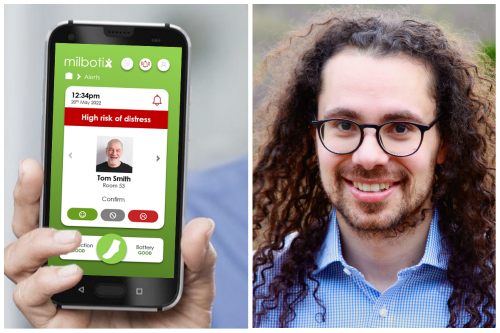

Left: The display that carers will see in the Milbotix app. Right: Milbotix founder and CEO Dr Zeke Steer

Inventor Dr Zeke Steer quit his job and took a PhD at Bristol Robotics Laboratory so he could find a way to help people like his great-grandmother, who became anxious and aggressive because of her dementia.

Milbotix’s smart socks track heart rate, sweat levels and motion to give insights on the wearer’s wellbeing – most importantly how anxious the person is feeling.

They look and feel like normal socks, do not need charging, are machine washable and provide a steady stream of data to carers, who can easily see their patient’s metrics on an app.

Current alternatives to Milbotix’s product are worn on wrist straps, which can stigmatise or even cause more stress.

Dr Steer said: “The foot is actually a great place to collect data about stress, and socks are a familiar piece of clothing that people wear every day.

“Our research shows that the socks can accurately recognise signs of stress – which could really help not just those with dementia and autism, but their carers too.”

Dr Steer was working as a software engineer in the defence industry when his great-grandmother, Kath, began showing the ill effects of dementia.

Once gentle and with a passion for jazz music, Kath became agitated and aggressive, and eventually accused Dr Steer’s grandmother of stealing from her.

Dr Steer decided to investigate how wearable technologies and artificial intelligence could help with his great-grandmother’s symptoms. He studied for a PhD at Bristol Robotics Laboratory, which is jointly run by the University of Bristol and UWE Bristol.

During the research, he volunteered at a dementia care home operated by the St Monica Trust. Garden House Care Home Manager, Fran Ashby said: “Zeke’s passion was clear from his first day with us and he worked closely with staff, relatives and residents to better understand the effects and treatment of dementia.

“We were really impressed at the potential of his assisted technology to predict impending agitation and help alert staff to intervene before it can escalate into distressed behaviours.

“Using modern assistive technology examples like smart socks can help enable people living with dementia to retain their dignity and have better quality outcomes for their day-to-day life.”

While volunteering Dr Steer hit upon the idea of Milbotix, which he launched as a business in February 2020.

“I came to see that my great grandmother wasn’t an isolated episode, and that distressed behaviours are very common,” he explained.

Milbotix are currently looking to work with innovative social care organisations to refine and evaluate the smart socks.

The business recently joined SETsquared Bristol, the University’s world-leading incubator for high growth tech businesses.

Dr Steer was awarded one of their Breakthrough Bursaries, which provides heavily subsidised membership to founders from diverse backgrounds. Dr Steer is also currently on the University’s QUEST programme, which support founders to commercialise their products.

Charity Alzheimer’s Society says there will be 1.6 million people with dementia in the UK by 2040, with one person developing dementia every three minutes. Dementia is thought to cost the UK £34.7 billion a year.

Meanwhile, according to the Government autism affects 1% of the UK population, or some 700,000 people, 15-30% of whom are non-verbal part or all of the time.

Dr Steer is now growing the business: testing the socks with people living with mid to late-stage dementia and developing the tech before bringing the product to market next year. Milbotix will begin a funding round later this year.

Milbotix is currently a team of three, including Jacqui Arnold, who has been working with people living with dementia for 40 years.

She said: “These socks could make such a difference. Having that early indicator of someone’s stress levels rising could provide the early intervention they need to reduce their distress – be that touch, music, pain relief or simply having someone there with them.”

Milbotix will be supported by Alzheimer’s Society through their Accelerator Programme, which is helping fund the smart socks’ development, providing innovation support and helping test what it described as a “brilliant product”.

Natasha Howard-Murray, Senior Innovator at Alzheimer’s Society, said: “Some people with dementia may present behaviours such as aggression, irritability and resistance to care.

“This innovative wearable tech is a fantastic, accessible way for staff to better monitor residents’ distress and agitation.”

Professor Judith Squires, Deputy Vice-Chancellor at the University of Bristol, said: “It is fantastic to see Zeke using the skills he learnt with us to improve the wellbeing of some of those most in need.

“The innovative research that Zeke has undertaken has the potential to help millions live better lives. We hope to see Milbotix flourish.”