Automation Means Going Paperless

Smart elastomers are making the robots of the future more touchy-feely

Toyota announces new capabilities for domestic robots

Zimmer Group System Technology – Development Competence at Just the Right Time

Combating fatigue with autonomy: Human-robot collaboration for manufacturing

Combating fatigue with autonomy: Human-robot collaboration for manufacturing

Hyundai Motor Group Completes Acquisition of Boston Dynamics from SoftBank

A robot on EBRAINS has learned to combine vision and touch

Robot-assisted surgery: Putting the reality in virtual reality

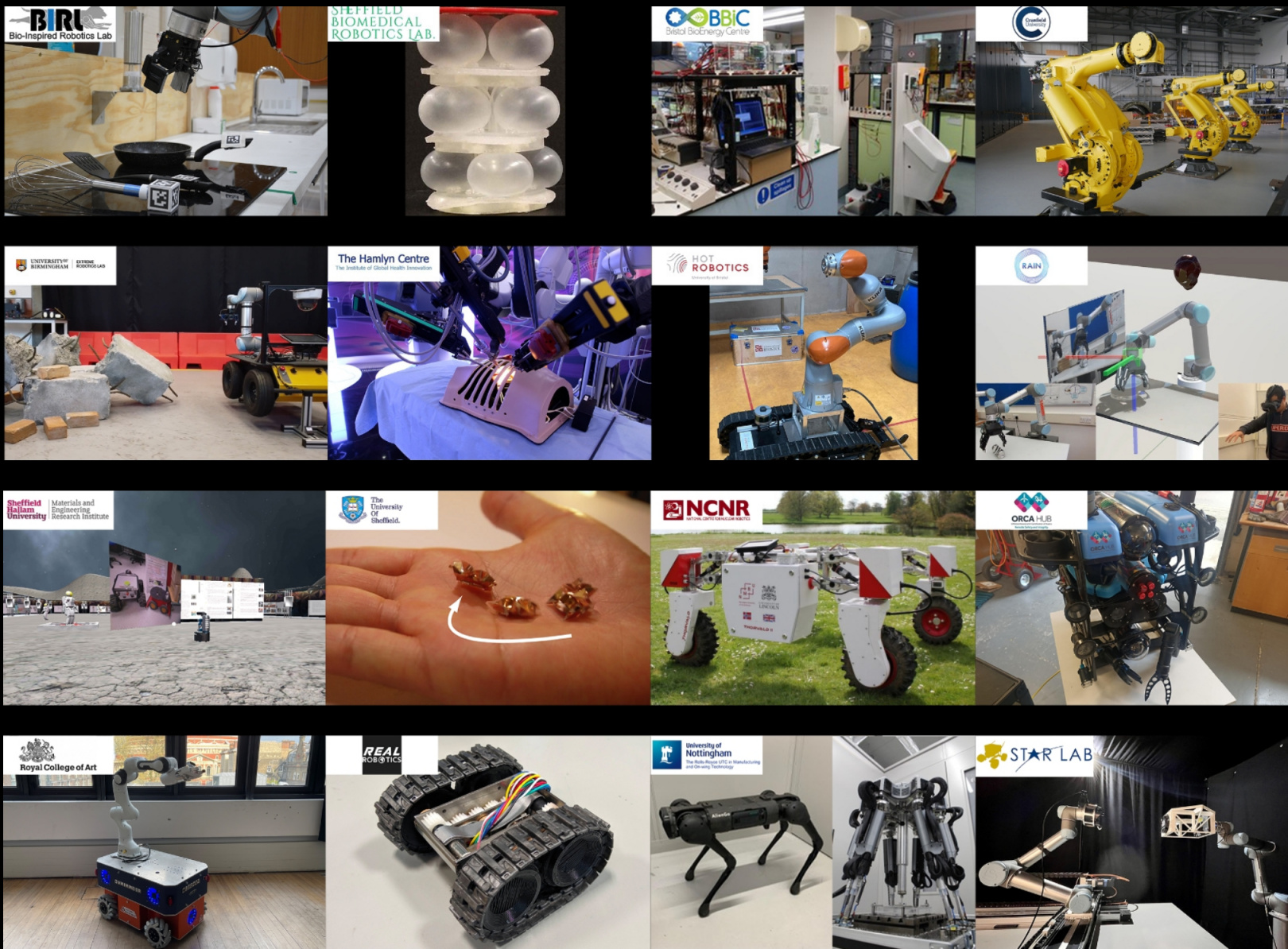

Robot Lab Live at the UK Festival of Robotics 2021 #RobotFest

For five years, the EPSRC UK Robotics and Autonomous Systems (UK-RAS) Network have been holding the UK Robotics Week. This year’s edition kicked off on the 19th of June as the UK Festival of Robotics with the aim of boosting public engagement in robotics and intelligent systems. The festival features online events, special competitions, and interactive activities for robot enthusiasts of all ages. Among them, we chose to recommend you the Robot Lab Live session that will take place online on Wednesday the 23rd of June, 4pm – 6pm (BST).

Robot Lab Live is a virtual robotics showcase featuring 16 of the UK’s top robotics research groups. Each team will show-off their cutting-edge robots and autonomous systems simultaneously to live audiences on YouTube. You can flick between different demos running during the two-hour livestream, ask questions and interact with the research teams in the chat. Here’s the link to watch the livestream.

Apart from Robot Lab Live, there are other interactive (and online!) events that we find of particular interest:

- Mosaix with Swarm Robot Tiles (Tuesday the 22nd of June, 4pm – 6pm BST): In this event, you will be able to remotely control your own Tile at the Bristol Robotics Laboratory to create collective art with other users. Tiles are small, 4-inch screens-on-wheels that users can draw on, colour, and move. ‘Mosaix’ emerges from the interactions between swarms of robot ‘Tiles’.

- Tech Tag (Thursday the 24th of June, 5pm – 7pm BST): Control one of our robots at Harwell campus in Oxford as they play a high-tech version of the schoolyard classic – tag. Visit this website to join one of the four robot teams (blue, purple, red or yellow) and vote for where your robot should go next to avoid being tagged. If you’re it – try to catch one of the other robots as quickly as you can! With live commentary from science communicator and presenter, Sam Langford.

- CSI Robot (Friday the 25th of June, 3pm – 4pm BST): Would you like to try being an accident investigator, finding out the cause of incidents involving humans and social robots? Then join us for this fun, interactive session!

To find out about more events, please visit this website.