Robots in the Food Service Industry

Face masks that can diagnose COVID-19

By Lindsay Brownell

Most people associate the term “wearable” with a fitness tracker, smartwatch, or wireless earbuds. But what if cutting-edge biotechnology were integrated into your clothing, and could warn you when you were exposed to something dangerous?

A team of researchers from the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology has found a way to embed synthetic biology reactions into fabrics, creating wearable biosensors that can be customized to detect pathogens and toxins and alert the wearer.

The team has integrated this technology into standard face masks to detect the presence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in a patient’s breath. The button-activated mask gives results within 90 minutes at levels of accuracy comparable to standard nucleic acid-based diagnostic tests like polymerase chain reactions (PCR). The achievement is reported in Nature Biotechnology.

“We have essentially shrunk an entire diagnostic laboratory down into a small, synthetic biology-based sensor that works with any face mask, and combines the high accuracy of PCR tests with the speed and low cost of antigen tests,” said co-first author Peter Nguyen, Ph.D., a Research Scientist at the Wyss Institute. “In addition to face masks, our programmable biosensors can be integrated into other garments to provide on-the-go detection of dangerous substances including viruses, bacteria, toxins, and chemical agents.”

Taking cells out of the equation

The SARS-CoV-2 biosensor is the culmination of three years of work on what the team calls their wearable freeze-dried cell-free (wFDCF) technology, which is built upon earlier iterations created in the lab of Wyss Core Faculty member and senior author Jim Collins. The technique involves extracting and freeze-drying the molecular machinery that cells use to read DNA and produce RNA and proteins. These biological elements are shelf-stable for long periods of time and activating them is simple: just add water. Synthetic genetic circuits can be added to create biosensors that can produce a detectable signal in response of the presence of a target molecule.

The researchers first applied this technology to diagnostics by integrating it into a tool to address the Zika virus outbreak in 2015. They created biosensors that can detect pathogen-derived RNA molecules and coupled them with a colored or fluorescent indicator protein, then embedded the genetic circuit into paper to create a cheap, accurate, portable diagnostic. Following their success embedding their biosensors into paper, they next set their sights on making them wearable.

“Other groups have created wearables that can sense biomolecules, but those techniques have all required putting living cells into the wearable itself, as if the user were wearing a tiny aquarium. If that aquarium ever broke, then the engineered bugs could leak out onto the wearer, and nobody likes that idea,” said Nguyen. He and his teammates started investigating whether their wFDCF technology could solve this problem, methodically testing it in more than 100 different kinds of fabrics.

Then, the COVID-19 pandemic struck.

Pivoting from wearables to face masks

“We wanted to contribute to the global effort to fight the virus, and we came up with the idea of integrating wFDCF into face masks to detect SARS-CoV-2. The entire project was done under quarantine or strict social distancing starting in May 2020. We worked hard, sometimes bringing non-biological equipment home and assembling devices manually. It was definitely different from the usual lab infrastructure we’re used to working under, but everything we did has helped us ensure that the sensors would work in real-world pandemic conditions,” said co-first author Luis Soenksen, Ph.D., a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Wyss Institute.

The team called upon every resource they had available to them at the Wyss Institute to create their COVID-19-detecting face masks, including toehold switches developed in Core Faculty member Peng Yin’s lab and SHERLOCK sensors developed in the Collins lab. The final product consists of three different freeze-dried biological reactions that are sequentially activated by the release of water from a reservoir via the single push of a button.

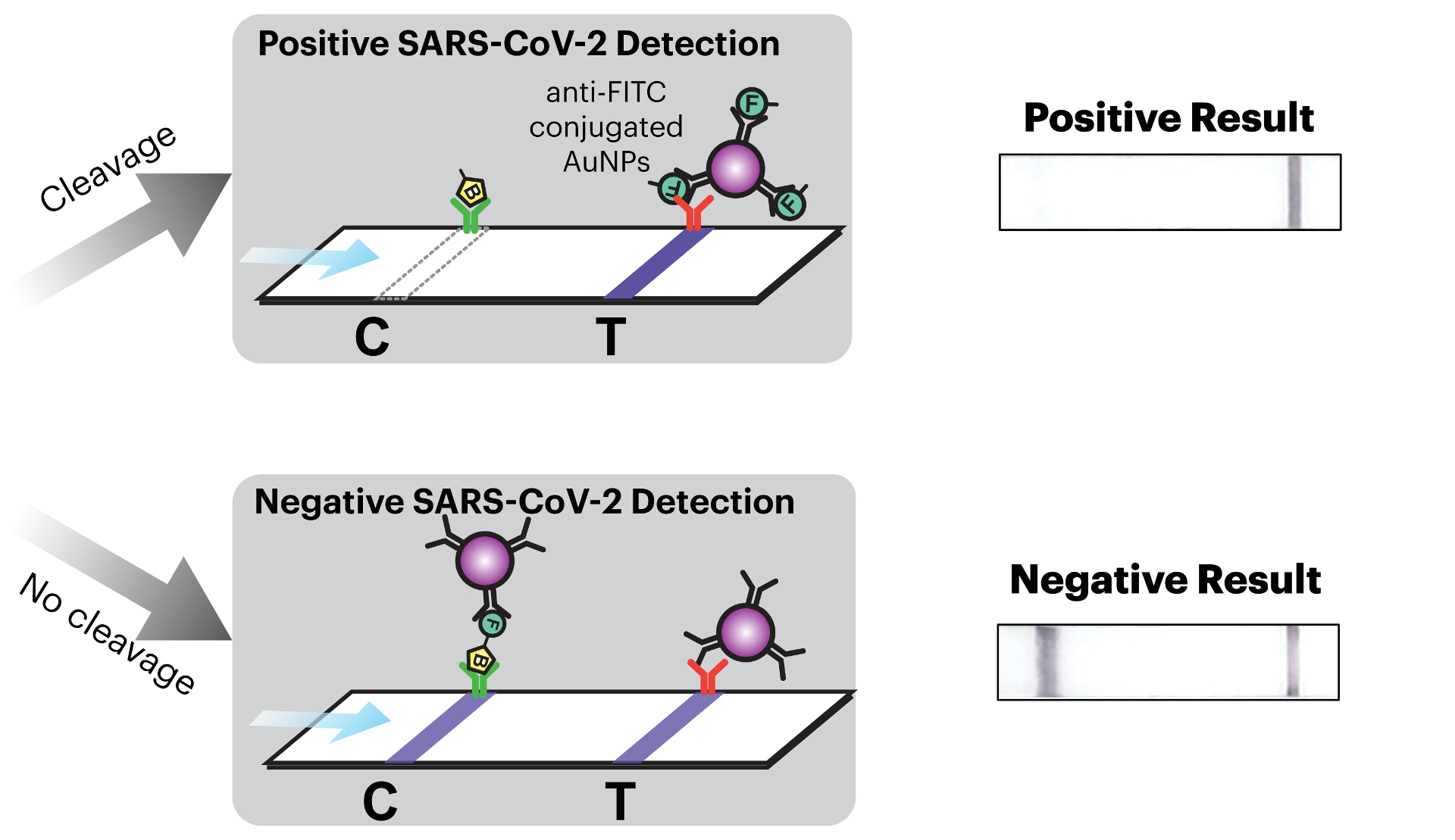

The first reaction cuts open the SARS-CoV-2 virus’ membrane to expose its RNA. The second reaction is an amplification step that makes numerous double-stranded copies of the Spike-coding gene from the viral RNA. The final reaction uses CRISPR-based SHERLOCK technology to detect any Spike gene fragments, and in response cut a probe molecule into two smaller pieces that are then reported via a lateral flow assay strip. Whether or not there are any Spike fragments available to cut depends on whether the patient has SARS-CoV-2 in their breath. This difference is reflected in changes in a simple pattern of lines that appears on the readout portion of the device, similar to an at-home pregnancy test.

The wFDCF face mask is the first SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid test that achieves high accuracy rates comparable to current gold standard RT-PCR tests while operating fully at room temperature, eliminating the need for heating or cooling instruments and allowing the rapid screening of patient samples outside of labs.

“This work shows that our freeze-dried, cell-free synthetic biology technology can be extended to wearables and harnessed for novel diagnostic applications, including the development of a face mask diagnostic. I am particularly proud of how our team came together during the pandemic to create deployable solutions for addressing some of the world’s testing challenges,” said Collins, Ph.D., who is also the Termeer Professor of Medical Engineering & Science at MIT.

Beyond the COVID-19 pandemic

The Wyss Institute’s wearable freeze-dried cell-free (wFDCF) technology can quickly diagnose COVID-19 from virus in patients’ breath, and can also be integrated into clothing to detect a wide variety of pathogens and other dangerous substances. Credit: Wyss Institute at Harvard University

The face mask diagnostic is in some ways the icing on the cake for the team, which had to overcome numerous challenges in order to make their technology truly wearable, including capturing droplets of a liquid substance within a flexible, unobtrusive device and preventing evaporation. The face mask diagnostic omits electronic components in favor of ease of manufacturing and low cost, but integrating more permanent elements into the system opens up a wide range of other possible applications.

In their paper, the researchers demonstrate that a network of fiber optic cables can be integrated into their wFCDF technology to detect fluorescent light generated by the biological reactions, indicating detection of the target molecule with a high level of accuracy. This digital signal can be sent to a smartphone app that allows the wearer to monitor their exposure to a vast array of substances.

“This technology could be incorporated into lab coats for scientists working with hazardous materials or pathogens, scrubs for doctors and nurses, or the uniforms of first responders and military personnel who could be exposed to dangerous pathogens or toxins, such as nerve gas,” said co-author Nina Donghia, a Staff Scientist at the Wyss Institute.

The team is actively searching for manufacturing partners who are interested in helping to enable the mass production of the face mask diagnostic for use during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as for detecting other biological and environmental hazards.

“This team’s ingenuity and dedication to creating a useful tool to combat a deadly pandemic while working under unprecedented conditions is impressive in and of itself. But even more impressive is that these wearable biosensors can be applied to a wide variety of health threats beyond SARS-CoV-2, and we at the Wyss Institute are eager to collaborate with commercial manufacturers to realize that potential,” said Don Ingber, M.D., Ph.D., the Wyss Institute’s Founding Director. Ingber is also the Judah Folkman Professor of Vascular Biology at Harvard Medical School and Boston Children’s Hospital, and Professor of Bioengineering at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences.

Additional authors of the paper include Nicolaas M. Angenent-Mari and Helena de Puig from the Wyss Institute and MIT; former Wyss and MIT member Ally Huang who is now at Ampylus; Rose Lee, Shimyn Slomovic, Geoffrey Lansberry, Hani Sallum, Evan Zhao, and James Niemi from the Wyss Institute; and Tommaso Galbersanini from Dreamlux.

This research was supported by the Defense Threat Reduction Agency under grant HDTRA1-14-1-0006, the Paul G. Allen Frontiers Group, the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, Harvard University, Johnson & Johnson through the J&J Lab Coat of the Future QuickFire Challenge award, CONACyT grant 342369 / 408970, and MIT-692 TATA Center fellowship 2748460.

Japan’s SoftBank suspends production of chatty robot Pepper

What Security Privileges Should We Give to AI?

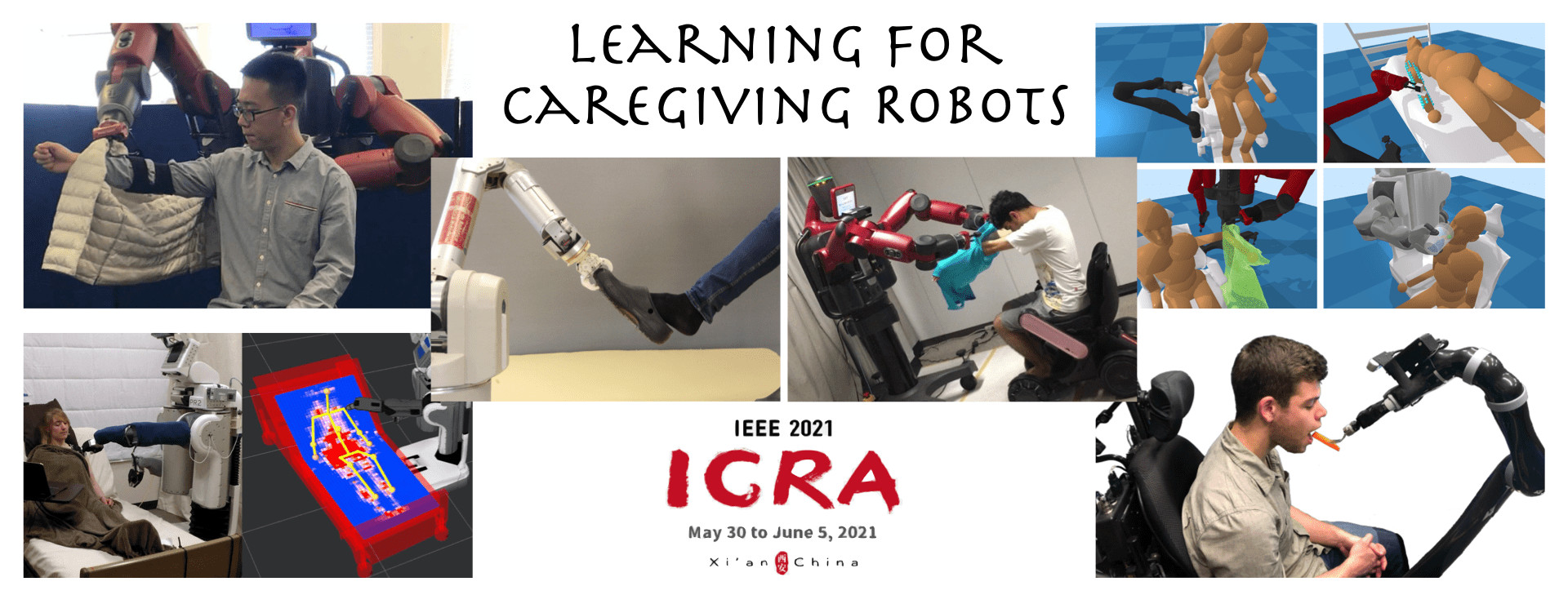

Learning for Caregiving Robots workshop at IEEE ICRA 2021

The Learning for Caregiving Robots workshop at IEEE ICRA 2021 discussed how learning can enable robotic systems towards achieving consistently efficient and safe human assistance across activities of daily living (ADLs). Here we bring you the recordings of the workshop, including talks from the nine invited speakers and two panel discussions.

Robotic caregivers could increase the independence of people with disabilities, improve quality of life, and help address growing societal needs, such as shortages of healthcare workers, aging populations that require care, and high healthcare costs. Using robotic technology to assist care-recipients in their daily lives may entail physically interacting with them, adapting to their preferences, and perceiving the environment for intelligent and safe assistance. These tasks can benefit from using data-driven machine learning techniques. Learning for caregiving in real homes depends on sensing and acting using real-world systems as well as metrics for success and generalization.

The primary objectives of the workshop were to explore the following questions:

- How can learning enable robotic systems to achieve efficient and safe assistance across (Instrumental) ADLs?

- What roles should (or should not) learning play for robotic caregiving?

- What are the opportunities and challenges of learning in robotic caregiving?

The workshop brought together renowned scientists and young researchers from the machine learning and assistive robotics communities to share and discuss solutions that can beneficially impact human society. Enjoy the playlist with all the recorded talks below!

How Are Smarter Robots Leading to Mass Customization in Manufacturing?

An autonomous drone for search and rescue in forests using optical sectioning algorithm

Simulations, real robots, and bloopers from the DOTS competition: Powering emergency food distribution using swarms

Results from the DOTS competition were released yesterday, after an intense month with teams from around the world designing new algorithms for robot swarms tasked with delivering emergency food parcels.

The Scenario

Increases in the number of emergency food parcels distributed by food banks have accelerated over the course of the coronavirus pandemic, particularly in those going to children. Robot swarms could help streamline the distribution of these emergency food parcels, while freeing up time for volunteers and workers to interface with the users and provide human contact.

What if you could unbox a swarm of robots and immediately use them to power your organisation and transport needs? You could use them to organise the stock room of a small retail shop, or retrieve boxes in a pop-up distribution centre for school lunches.

In the DOTS competition run jointly by the Bristol Robotics Laboratory, Toshiba Bristol Research and Innovation Laboratory and the South Gloucestershire Council’s UMBRELLA project, the robots used are called DOTS (Distributed Organisation and Transport Systems) and they fit the problem at hand: they don’t rely on maps or any complex infrastructure, making them both versatile and adaptable.

After years of research in swarm algorithms and hardware, we’re now at stage where we can think of real-world applications. Robot swarms make so much sense as out-of-the-box solutions that can scale and adapt to a variety of messy real-world environments.

Sabine Hauert, Associate Professor of Swarm Engineering and lead of the DOTS competition.

The Robots

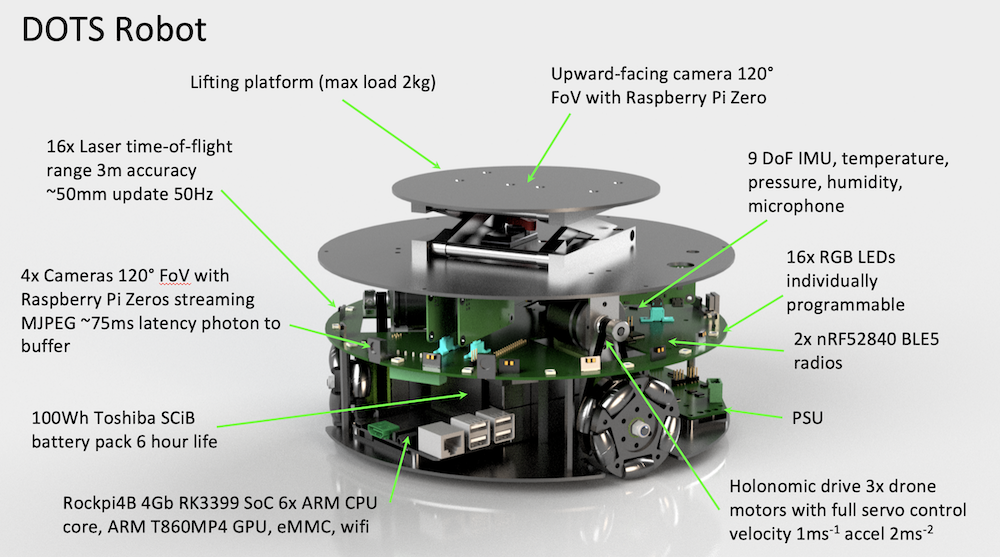

The DOTS are custom-built 25cm robots, that move fast, have long battery life (8 hours), can communicate through 5G, WiFI, and bluetooth, house a GPU, and can sense the environment locally, as well as lift and transport payloads (2kg per robot). They are housed in the new Industrial Swarm Arena at the Bristol Robotics Laboratory, which is accessible remotely and 5G enabled.

“It’s taken three years to design and build the DOTS robots and simulator. I wanted the DOTS to individually be quite capable, with the latest sensing and computational capabilities so they could make sense of the world around them using distributed situational awareness. It’s been really rewarding to see them in action, and to see that others can use them too. Many of these robots were built at my house during lockdown where I have a dedicated workshop.” said Simon Jones, Research Fellow and designer of the DOTS at University of Bristol.

The Challenge

Over the past few weeks, participants in the competition have brainstormed and engineered solutions to tackle the challenge. The warehouse is a simulated 4m x 4m x 4m room in Gazebo with a 0.5m-wide strip along the right wall, acting as the dropoff zone. The 10 “carriers” that the robots must retrieve are scattered at random. Following the swarm robotics paradigm, each robot runs the same codebase: the challenge is therefore to engineer a solution where the emergent behaviour of the collective swarm results in fast retrieval.

One of the simplest solutions is for a robot to perform a random walk. As soon as a sensor detects a carrier, it can home in on the carrier and pick it up. Given enough time the robots will, collectively, retrieve all the carriers. From this basic implementation, more complex behaviours can be layered such as adding a bias for movement in a particular direction or having the robots interact to repulse or attract.

Of course, in the real world, the robots would have to contend with obstacles as well as faults in their hardware and software. The submitted solutions are also tested for their robustness and ability to overcome these hurdles. An extra level of complexity is added with the task of retrieving carriers in a given order.

“It’s been a great learning experience to see the whole pipeline from code to simulation to running with the real robots in the arena – feels like this is where progress is made towards that vision of robots integrated into our everyday lives”, said Suet Lee, PhD Student at University of Bristol who helped support the teams.

The Results

With 7 team submissions from around the world, it was exciting to see what solutions would emerge. In the end, scores were quite tight. For teams that needed extra time, we’ll be hosting a demo round later this summer.

The winners were Swarmanauts. The team included David Garzon Ramos, Jonas Kuckling, and Miquel Kegeleirs, PhD students at IRIDIA, the artificial intelligence lab of the Université libre de Bruxelles, Brussels, Belgium. They are all part of the ERC DEMIURGE project team (PI Mauro Birattari) where they investigate the automatic design of collective behaviours for robot swarms.

You can see their controller in action over the 6 tested scenarios here (unordered retrieval, unordered with lost robots, unordered with obstacles, ordered retrieval, ordered with lost robots, ordered with obstacles)

“It was exciting to participate in the DOTS competition. We enjoyed the challenge of devising and testing coordination strategies for an industry-oriented robot swarm. Next time we would like to also try automatic methods for designing the collective behavior of the robots”, said David.

In second came BusyB with team members Simon Obute and Rey Lei.

And finally, in third we had Simple Solution by Hany Hamed and their feisty controller.

Winners will be receiving this fancy award at home soom.

There were plenty of bloopers along the way with all teams, here’s one sample of how things can go wrong in slow motion:

Finally, well done to all the other teams, UGA Hero Lab, Missing in Action, Str. Robot, and C5PO for their great submissions.

Translation to reality

In the end, a simulation is no substitute for a real world environment, as useful as it is for testing. What occurs is the “reality-gap”, the error that arises from the difference between the noisy real-world environment and the simplified simulation environment. Simon was able to demonstrate a baseline controller in reality in the video below. To help transfer, the same code designed in ROS2, is built to run both in simulation and reality. Some changes were needed, such as slowing down the robots to avoid motion blur on the cameras, but many of the behaviours translated well like the obstacle avoidance, and overall swarm strategy.

It was an amazing experience to work with our cool lab-built robots! I enjoyed designing Hardware kits and it was rewarding to see it all working in real-life.

Aswath G Indra, MSc Robotics Student at University of Bristol.

Next steps

For a first DOTS Competition, it was great fun and we’re really happy with what was achieved by all involved. We have many of ideas for next year, like how to speed up computation, adding new tasks (like organising the warehouse), and will be looking to give more time to the teams to use the real-hardware remotely.

Mahesh Sooriyabandara, Managing Director at the Toshiba Bristol Research and Innovation Laboratory, said “This is a great first step towards making an internet of robots and robot swarms that are useable out of the box. We’ve been working with the Bristol Robotics Laboratory for the past 3 years to build first the robots and then the new Industrial Swarm Arena. We’re hoping many can use this infrastructure in the future, running their code in a digital twin before transferring to the new swarm testbed”.

The DOTS Competition was supported by Simon Jones, Emma Milner, Suet Lee, James Wilson, Aswath Ganesan Indra, Sabine Hauert, and the Toshiba BRIL team.

RoboDK Software Helps Cut Aircraft Washing Time by 95%

Robot farmers could improve jobs and help fight climate change – if they’re developed responsibly

Farming robots that can move autonomously in an open field or greenhouse promise a cleaner, safer agricultural future. But there are also potential downsides, from the loss of much-needed jobs to the safety of those working alongside the robots.

To ensure that the use of autonomous robots on farms creates more benefits than losses, a process of responsible development is required. Society as a whole needs to be involved in setting the trajectories for future farming.

We are part of a project called Robot Highways, which is currently demonstrating multiple uses for autonomous robots made by Saga Robotics on a fruit farm in south-east England. Robots are now treating plant diseases in fields and glasshouses, and will be mapping terrain, picking, packing, and providing logistical support to workers over the course of the project. This is achieved by attaching different tools to an autonomous “base robot”.

In this way, autonomous farming robots have the potential to do some of the laborious agricultural work for which farmers in some countries often struggle to find employees at a cost that keeps food prices competitive. Our project has produced an estimate that robots may eventually help reduce the number of human farm workers needed by up to 40%.

At the same time, robots could help create new jobs. The UK’s National Farmers’ Union argues that increasing use of digital technologies in farms will attract younger, skilled people to a sector struggling with an ageing workforce.

Matt Munro, Saga Robotics, Author provided

There could also be environmental benefits. Swapping traditional, fossil fuel-powered farm machinery for electric robots charged from renewable sources will cut farming’s carbon emissions. Robots equipped with ultraviolet lights that can kill mildew on plants could reduce fungicide use by up to 90%.

Machines like those produced by the Small Robot Company can navigate in tight spaces between objects like trees, so could potentially be used in agroforestry systems to perform weeding, disease treatment and mapping. They could also help reduce chemical use on farms by targeting individual plants, rather than whole fields.

NASAHQPhoto/Flickr

However, unrestricted use of autonomous farming robots could also create problems. In parts of the world where there is not an agricultural labour shortage, reducing the demand for human workers means people will need resources and opportunities to retrain in other sectors. They may just end up moving into dull, dangerous and underpaid jobs in other industries such as mining, which will be needed to produce the materials to make the robots.

Humans who are left on the farm – or walkers on footpaths – will face health and safety concerns from having to work alongside the robots. The possibility of someone hacking a farm robot and forcing it to do their bidding cannot be overlooked. And poorer farms that can’t afford robots at all are likely to be left at a disadvantage.

There are also concerns over the ownership of the data collected by robots operated by commercial companies – and whether that data will be used for the benefit of those companies, rather than the farmers.

Responsible development

To make sure farming robots are developed responsibly, we need to get those people who might be affected by the technology –- from manufacturers and regulators to rural communities -– thinking about all its possible implications.

This might include so-called “Wizard of Oz” studies, in which remote controlled robots are tested alongside human users in order to simulate what reactions and consequences fully autonomous robots might produce once the technology is ready. This would allow robot designers to save money and manage expectations by studying user experience at the early stages of development. Another option is hosting “robot movie nights” to help show the public how robots on the farm would behave.

Matt Munro, Saga Robotics, Author provided

Once countries allow autonomous robots to be used on farms, safety and data-ownership regulations will need to be swiftly updated. In Australia, a code of practice for such robots has been developed in the crop sector and similar work is underway in the UK. This will set out robots’ obligations, state the conditions in which robots can be used, and determine who is responsible for worker and public safety.

The stakes of getting things wrong are high. Injured workers, hacked or unreliable robots, or negative consumer perception could all stand in the way of the promises of autonomous robots being realised. To help avoid this, governments can start providing rural digital and internet infrastructure, training, and financial support so that farmers can hit the ground running if autonomous robots hit the market.

Will we see autonomous robots picking fruit across Britain by 2025 – or even sooner? That depends: not on the quality of our technology alone, but also on our ability to work together to listen, learn and respond to the needs of farmers and society alike.

![]()

David Rose receives funding from UKRI (Innovate UK).

Marc Hanheide receives funding from UKRI and the EU Commission, and owns shares in SAGA Robotics.

Simon Pearson receives funding from UKRI. He is Co-Chair of the DEFRA Automation and Robotics Review for Horticulture

Original post published in The Conversation.