Robohub and AIhub’s free workshop trial on sci-comm of robotics and AI

Would you like to learn how to tell your robotics/AI story to the public? Robohub and AIhub are testing a new workshop to train you as the next generation of communicators. You will learn to quickly create your story and shape it to any format, from short tweets to blog posts and beyond. In addition, you will learn how to communicate about robotics/AI in a realistic way (avoiding the hype), and will receive tips from top communicators, science journalists and ealy career researchers. If you feel like being part of our beta testers, join this free workshop to experience how much impact science communication can have on your professional journey!

The workshop is taking place on Friday the 30th of April, 10am-12.30pm (UK time) via Zoom. Please, sign up by sending an email to daniel.carrillozapata@robohub.org.

Pepper the robot talks to itself to improve its interactions with people

DLL: A map-based localization framework for aerial robots

Robots benefit special education students

Virtual to Reality: Delivering Accuracy to The Real World

ULTRA-SWARM: Creating digital twins of UAV swarms for firefighting and aid delivery

For my PhD, I’m studying how global problems such as wildfires and aid delivery in remote areas can benefit from innovative technologies such as UAV (unmanned aerial vehicle) swarms.

Every year, vast areas of forests are destroyed due to wildfires. Wildfires occur more frequently as climate change induces extreme weather conditions. As a result, wildfires are often larger and more intense. Over the past 5 years, countries around the globe witnessed unprecedented effects of wildfires. Greece has seen the deadliest wildfire incident in its modern history, Australia witnessed 18,636,079 hectares being burnt and British Columbia faced wildfire incidents that burnt 1,351,314 hectares.

Rather than jump straight in to the design of swarm algorithms for UAVs in these scenarios, I spent a year speaking with firefighters around the world to ask about their current operations and how UAVs could help. This technique is called mutual shaping where end users cooperate with developers to co-create a system. It’s been interesting to see the challenges they face, their openness to drones and their ideas on the operation of a swarm. Firefighters face numerous challenges in their operations. Their work is dangerous and they need to ensure the safety of citizens and themselves. However, they often don’t have enough information about the environment they are deploying in. The good news is that UAVs are already used by firefighters to retrieve information during their operations, usually during very short human-piloted flights with small off-the-shelf drones. Having larger drones, with longer autonomy and higher payload, could provide high-value information to firefighters or actively identify and extinguish newly developed fire fronts.

I think one of the reasons we don’t have these swarms in these applications is that 1) we didn’t have the hardware capabilities (N robots with high-payload at a reasonable cost) , 2) we don’t have the algorithms that allow for effective swarm deployments at the scale of a country (necessary to monitor for forest fires), and 3) we can’t easily change our swarm strategies on the go based on what is happening in reality. That’s where digital twins come in. A digital twin is the real-time virtual representation of the world we can use to iterate solutions. The twin can be simplistic in 2D or a more realistic 3D representation, with data from the real-world continuously updating the model.

To develop this framework for digital twins we’re starting a new project with Windracers ltd, Distributed Avionics ltd, and the University of Bristol co-funded by Innovate UK. Windracers ltd. has developed a novel UAV: the ULTRA platform, that can transport 100kg of payload over a 1000km range. Distributed Avionics specialises in high-reliability flight control solutions and Hauert Lab, which engineers swarm systems across scales – from huge number of tiny nanoparticles for cancer treatment to robots for logistics.

In the future, we aim to use the same concepts to enable aid delivery using UAV swarms. The 2020 Global Report on Food Crises states that more than 135 million people across 53 countries require urgent food, nutrition, and livelihoods assistance. Aerial delivery of such aid could help access remote communities and avoid in-person transmission of highly infectious diseases such as COVID-19.

Here’s a video presenting the concept:

By the end of this project, we are hoping to demonstrate the deployment of 5 real UAVs that will be able to interact with a simple digital twin. We also want to test live deployment of the control swarm system on the UAVs.

Are you a firefighter, someone involved in aid delivery, do you have other ideas for us. We’d love to hear from you.

A technique to plan paths for multiple robots in flexible formations

Design and Operation Features of a BDC Motor Controller

On sustainable robotics

The climate emergency brooks no compromise: every human activity or artefact is either part of the solution or it is part of the problem.

I’ve worried about the sustainability of consumer electronics for some time, and, more recently, the shocking energy costs of big AI. But the climate emergency has also caused me to think hard about the sustainability of robots. In recent papers we have defined responsible robotics as

the application of Responsible Innovation in the design, manufacture, operation, repair and end-of-life recycling of robots, that seeks the most benefit to society and the least harm to the environment.

I will wager that few robotics manufacturers – even the most responsible – pay much attention to repairability and recyclability of their robots. And, I’m ashamed to say, very little robotics research is focused on the development of sustainable robots. A search on google scholar throws up a handful of excellent papers detailing work on upcycled and sustainable robots (2018), sustainable robotics for smart cities (2018), green marketing of sustainable robots (2019), and sustainable soft robots (2020).

I was therefore delighted when, a few weeks ago, my friend and colleague Michael Fisher, drafted a proposal for a new standard on Sustainable Robotics. The proposal received strong support from the BSI robotics committee. Here is the formal notice requesting comments on Michael’s proposal: BS XXXX Guide to the Sustainable Design and Application of Robotic Systems.

So what would make a robot sustainable? In my view it would have to be:

- Made from sustainable materials. This means the robot should, as far as possible, use recycled materials (plastics or metals), or biodegradable materials like wood. Any new materials should be ethically sourced.

- Low energy. The robot should be designed to use as little energy as possible. It should have energy saving modes. If an outdoor robot then is should use solar cells and/or hydrogen cells when they become small enough for mobile robots. Battery powered robots should always be rechargeable.

- Repairable. The robot would be designed for ease of repair using modular, replaceable parts as much as possible – especially the battery. Additionally the manufacturers should provide a repair manual so that local workshops could fix most faults.

- Recyclable. Robots will eventually come to the end of their useful life, and if they cannot be repaired or recycled we risk them being dumped in landfill. To reduce this risk the robot should be designed to make it easy re-use parts, such as electronics and motors, and re-cycle batteries, metals and plastics.

These are, for me, the four fundamental requirements, but there are others. The BSI proposal adds also the environmental effects of deployment (it is unlikely we would consider a sustainable robot designed to spray pesticides as truly sustainable), or of failure in the field. Also the environmental effect of maintenance; cleaning materials, for instance. The proposal also looks toward sustainable, upcyclable robots as part of a circular economy.

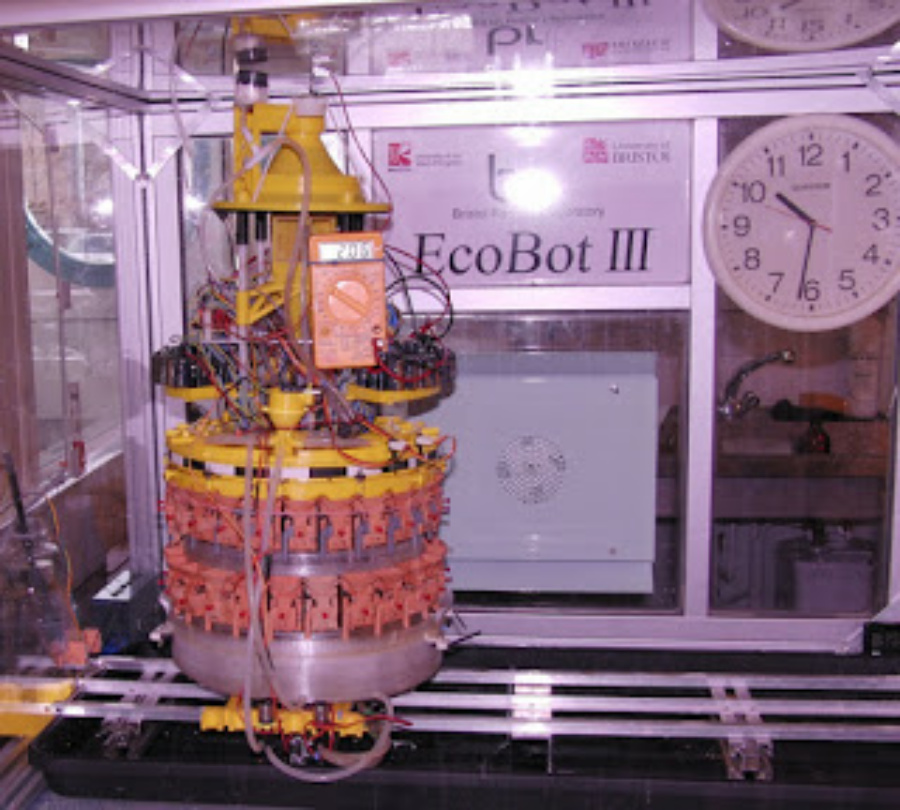

This is Ecobot III, developed some years ago by colleagues in the Bristol Robotics Lab’s Bio-energy group. The robot runs on electricity extracted from biomass by 48 microbial fuel cells (the two concentric brick coloured rings). The robot is 90% 3D printed, and the plastic is recyclable.

I would love to see, in the near term, not only a new standard on Sustainable Robotics as a guide (and spur) for manufacturers, but the emergence of Sustainable Robotics as a thriving new sub-discipline in robotics.

Army researchers create pioneering approach to real-time conversational AI

Pickle’s new robot works with people to get your online orders delivered sooner.

Tailing new ideas: Cheetah-inspired design enables better robot movement

Amanda Prorok’s talk – Learning to Communicate in Multi-Agent Systems (with video)

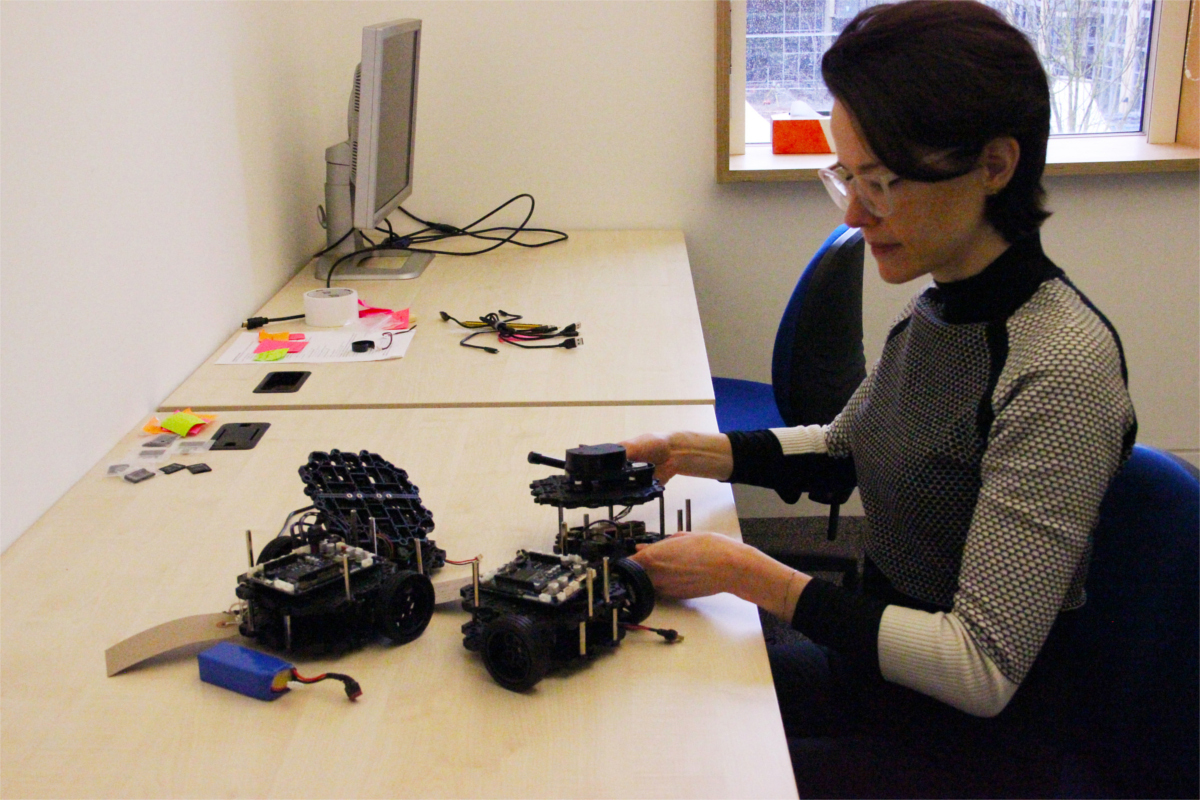

In this technical talk, Amanda Prorok, Assistant Professor in the Department of Computer Science and Technology at Cambridge University, and a Fellow of Pembroke College, discusses her team’s latest research on what, how and when information needs to be shared among agents that aim to solve cooperative tasks.

Abstract

Effective communication is key to successful multi-agent coordination. Yet it is far from obvious what, how and when information needs to be shared among agents that aim to solve cooperative tasks. In this talk, I discuss our recent work on using Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) to solve multi-agent coordination problems. In my first case-study, I show how we use GNNs to find a decentralized solution to the multi-agent path finding problem, which is known to be NP-hard. I demonstrate how our policy is able to achieve near-optimal performance, at a fraction of the real-time computational cost. Secondly, I show how GNN-based reinforcement learning can be leveraged to learn inter-agent communication policies. In this case-study, I demonstrate how non-shared optimization objectives can lead to adversarial communication strategies. Finally, I address the challenge of learning robust communication policies, enabling a multi-agent system to maintain high performance in the presence of anonymous non-cooperative agents that communicate faulty, misleading or manipulative information.

Biography

Amanda Prorok is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Computer Science and Technology, at Cambridge University, UK, and a Fellow of Pembroke College. Her mission is to find new ways of coordinating artificially intelligent agents (e.g., robots, vehicles, machines) to achieve common goals in shared physical and virtual spaces. Amanda Prorok has been honored by an ERC Starting Grant, an Amazon Research Award, an EPSRC New Investigator Award, an Isaac Newton Trust Early Career Award, and the Asea Brown Boveri (ABB) Award for the best thesis at EPFL in Computer Science. Further awards include Best Paper at DARS 2018, Finalist for Best Multi-Robot Systems Paper at ICRA 2017, Best Paper at BICT 2015, and MIT Rising Stars 2015. She serves as Associate Editor for IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters (R-AL), and Associate Editor for Autonomous Robots (AURO). Prior to joining Cambridge, Amanda Prorok was a postdoctoral researcher at the General Robotics, Automation, Sensing and Perception (GRASP) Laboratory at the University of Pennsylvania, USA. She completed her PhD at EPFL, Switzerland.

Featuring Guest Panelist(s): Stephanie Gil, Joey Durham

The next technical talk will be delivered by Koushil Sreenath from UC Berkeley, and it will take place on April 23 at 3pm EDT. Keep up to date on this website.