How Robotics Are Being Used in the Packaging Industry

All-terrain microrobot flips through a live colon

Scientists develop ‘mini-brains’ to help robots recognize pain and to self-repair

Staying Competitive with Automation

In-layer normalization techniques for training very deep neural networks

Robots are helping to advance developmental biology

Taking a CAD/CAM approach to Offline Robotic Programming

Robot swarms follow instructions to create art

Human-Robot Collaboration for Assembling Tasks in Manufacturing

How to lead AI projects

Artificial intelligence is becoming mainstream and many organizations, startups and big corporates alike, are now starting internal AI projects or are incooperating AI into other existing IT. There's just one problem. Leading AI projects are very different from leading in traditional IT.

As a result many AI projects either fail or ignite frustration with project participants, users of the AI and the management involved. They are unaware that they are now in a new paradigm and should have different expectations than usually have to IT. Even implementing off-the-shelf AI components or systems can cause problems that are not usual to the organization.

This is very understandable. A few years ago AI was still something a few big techs and the universities were engaged with but for the masses a distant future. So very few leaders and project managers have experience in the AI-field, that they are suddenly thrown into

So what is so different about AI projects?

The keyword here is uncertainty. The big difference between traditional IT and AI is how much certainty is available. The low certainty is due to the experimental nature of AI. The AI paradigm is experimental in the sense that you can’t predict the road to the finished product. You can't plan the inner workings of AI models before you have created it and you don't know exactly what data you will need or how much data. Lastly you don’t know how well the AI will work. So setting up expectations for the finished solution can be very difficult. In many ways AI development is very much comparable with vaccine development. It's impossible to know in advance if your project will even be successful and most of the insights you need will be acquired while developing. This is very much in contrast the IT paradigm we know. The consensus of traditional IT projects is to precise planning, estimation and achieve a preset list of business objectives as timely and accurate as possible. For that reason we have developed an expertise in for example, planning tools and estimation techniques. But suddenly with the entrance of AI a lot of these skills are no longer useful. In fact they can be downright damaging in an experimental paradigm. If management demands deadlines and accurate estimates the project is bound to fail as it will never be able to deliver.

The first step is admitting

In order to lead in the AI domain you first of all, must acknowledge that this is a new paradigm and you must speak about it openly. When working in a new paradigm the most important tool is to be vocal about the new rules of engagement. With very little certainty in AI, expectation management is already approaching an art. So if you are not even in a dialogue with the project stakeholders about how the new way of working is, expectations will never align. So be very clear about this up front. Even as you’re making the business case you have to be clear that you cannot know either the costs nor revenue generated by an AI project. Not everyone will like it and you will see resistance but it’s much better that you take the conflicts before the project starts.

It's a culture thing

The enabler to get acceptance from stakeholders to work in this kind of uncertainty is the right organizational culture. As a leader it is your responsibility to massage and try to shift the culture in a direction that works with experimental AI projects. If there’s a mismatch between the paradigm you work in and the culture, you will get in trouble in no time.

One of the important features in an experimental culture is the willingness to accept null results exactly like the scientific community does. This is not just the usual preach about accepting failure and mistakes. This is a culture that sees a lot of hard work amounting to no more than the knowledge that a specific solution is not viable.

The experimental culture that fits AI development is very much in line with the learning culture, a cultural style found in the eight distinct culture styles of corporate culture. Other cultural styles such as Results culture and Safety culture can be in sharp contrast to the learning style on crucial points when working with AI. The styles are respectively very keen on achieved results and accurate planning. With AI that offers no certainty for either results or predictability this can quickly conflict.

Be visionary

When leading under uncertainty, leading through a strong vision is very effective. Leading through a strong vision is very much in line with the Purpose culture style. I like to compare it to Columbus' journey to America. Not knowing what to expect on the way or if the journey would even see any kind of success, Columbus still managed to get funding and a reliable crew. Columbus was well known for being extremely strong in his vision and I would attribute at least some of his voyage success to a strong vision. The trick here is to be specific about what you envision on the other side of uncertainty. How will everything look and feel when the project is done?

In conclusion it’s very effective to actively use the culture to support AI development since the alternative might be that it will have that working against you. And organizational culture is definitely one of the stronger forces of the universe.

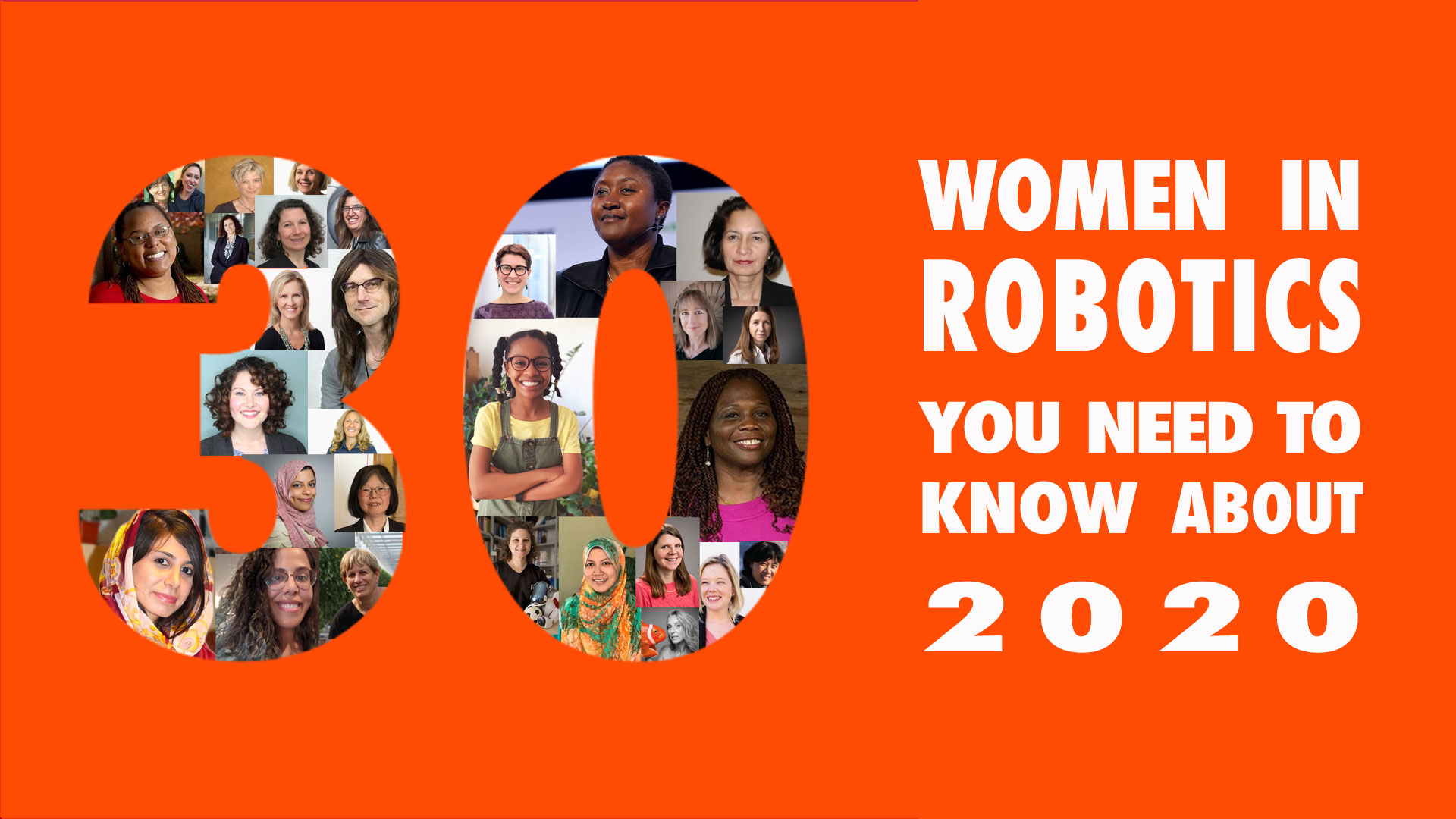

30 women in robotics you need to know about – 2020

It’s Ada Lovelace Day and once again we’re delighted to introduce you to “30 women in robotics you need to know about”! From 13 year old Avye Couloute to Bala Krishnamurthy who worked alongside the ‘Father of Robotics’ Joseph Engelberger in the 1970s & 1980s, these women showcase a wide range of roles in robotics. We hope these short bios will provide a world of inspiration, in our eighth Women in Robotics list!

In 2020, we showcase women in robotics in China, Japan, Malaysia, Israel, Australia, Canada, United States, United Kingdom, Switzerland, Israel, Norway, Spain, The Netherlands, India and Iran. There are researchers, industry leaders, and artists. Some women are at the start of their careers, while others have literally written the book, the program or the standards.

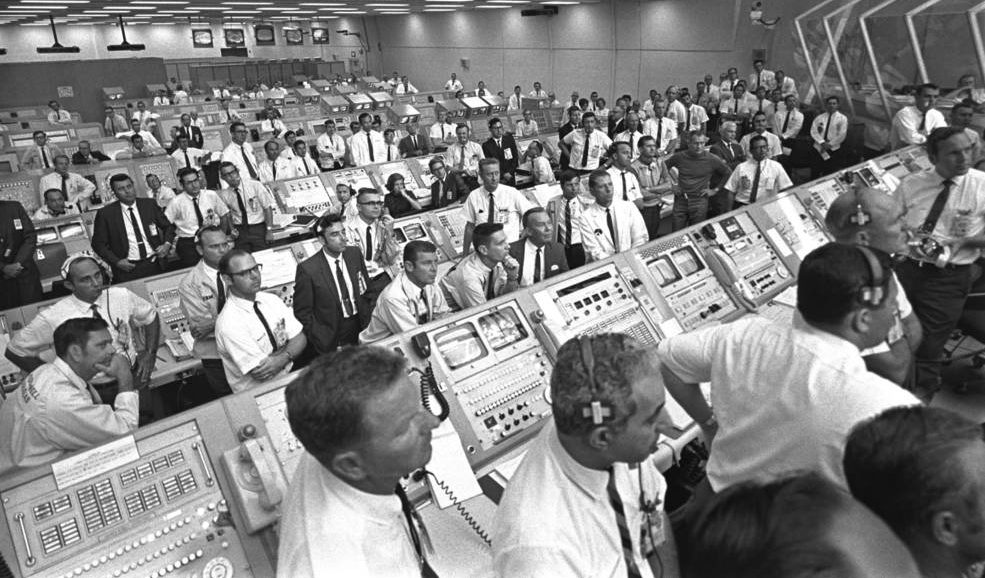

We publish this list because the lack of visibility of women in robotics leads to the unconscious perception that women aren’t making newsworthy contributions. We encourage you to use our lists to help find women for keynotes, panels, interviews etc. Sadly, the daily experience of most women in robotics still looks like this famous NASA control room shot from the 1969 Apollo 11 moon landing, with one solitary woman in the team. It has taken sixty years for the trailblazers like Joann Morgan, Katherine G. Johnson, Dorothy Vaughan, Mary Jackson and Poppy Northcutt to become well known. And finally now we have a woman, Charlie Blackwell-Thompson, serving as Launch Director for the upcoming Artemis Mission, and another, Gwynne Shotwell, serving as President and COO of SpaceX.

In 2019, women still accounted for less than a quarter (23.6%) of those working in natural and applied sciences and related occupations. In these occupations, women earned, on average, \$0.76 to every \$1.00 earned by men in annual wages, salaries, and commissions in 2018. [ref Catalyst.org ]

This issue is even more pervasive and devastating if you are a person of color. We have always strived to showcase a wide range of origins and ethnicities in our annual list, and this year, as well as four African American roboticists, our list includes the first African American female CEO of a company valued over $1Billion USD. This is just a small step forward, but we’re pleased to announce the recent launch of the Black in Robotics organization, as well as greater recognition of the citation problem.

The citation problem is expected to significantly disadvantage women and people of color due to the historical lack of women followed by the recent growth of large scientific teams, multiplying exclusion. For example, Nature recently published a paper on the impact of NumPy, a significant scientific resource. NumPy was originally developed by many contributors. But the authoritative citation is likely to belong to this description paper, which has 26 authors, all male. [ref Space Australia]

On a positive note, many individuals and organizations intentionally try to reverse this bias. For example, Tulane University just published a guide to help you calculate how much of your reading list includes female authors and a citation guide, similar to the CiteHer campaign from BlackComputeher.org. And as Bram Vanderborght, editor of IEEE Robotics and Automation magazine pointed out in the March 2020 issue, “Scientists are starting to consider how gender biases materialize in physical robots. The danger is that robot makers, consciously or not, may reinforce gender stereotypes and inadvertently create even greater deterrents for young, underrepresented people interested in joining our field.”

We hope you are inspired by these profiles, and if you want to work in robotics too, please join us at Women in Robotics. We are now a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization, but even so, this post wouldn’t be possible if not for the hard work of volunteers; Andra Keay, Hallie Siegel, Sabine Hauert, Sunita Pokharel, Ioannis Erripis, Ron Thalanki and Daniel Carrillo Zapata.

Online events to look out for on Ada Lovelace Day 2020

Tomorrow the world celebrates Ada Lovelace Day to honor the achievements of women in science, technology, engineering and maths. We’ve specially chosen a couple of online events featuring amazing women in robotics and technology. You can enjoy their talks in the comfort of your own home.

Ada Lovelace Day: The Near Future (panel discussion)

Organized by Ada Lovelace Day, this panel session will be joined by Dr Beth Singler (Junior Research Fellow in Artificial Intelligence at the University of Cambridge), Prof Praminda Caleb-Solly (Professor of Assistive Robotics and Intelligent Health Technologies at the University of the West of England), Dr Anat Caspi (director of the Taskar Center for Accessible Technology, University of Washington) and Dr Chanuki Seresinhe (visiting data science researcher at The Alan Turing Institute). The event will take place at 4pm (UTC). You can register here.

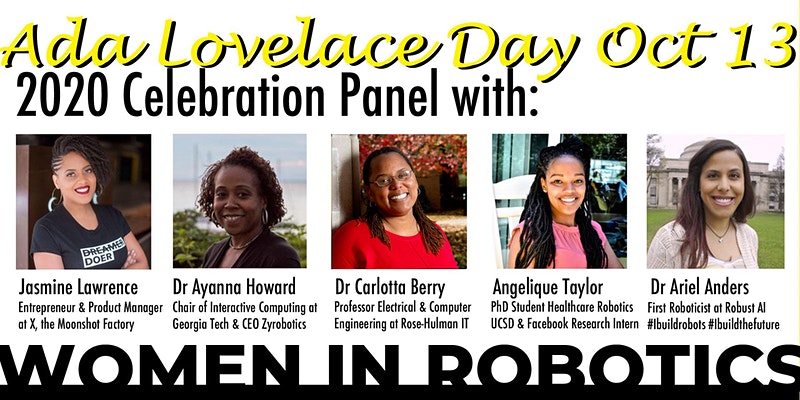

Ada Lovelace Day 2020 Celebration of Women in Robotics

Hosted by UC CITRIS CPAR and Silicon Valley Robotics, this event will be joined by Dr Ayanna Howard (Chair of Interactive Computing Georgia Tech), Dr Carlotta Berry (Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology), Angelique Taylor (PhD Candidate at the Healthcare Robotics Lab in UCSD and Facebook Research Intern), Dr Ariel Anders (First Technical Hire at Robust.ai) and Jasmine Lawrence, (Product Manager at X, the Moonshot Factory). This event will take place at 1am (UTC). You can register here.

Tomorrow we will also publish our 2020 list of women in robotics you need to know about. Stay tuned!