The gendering of robots is something I’ve found fascinating since I first started building robots out of legos with my brother. We all ascribe character to robots, consciously or not, even when we understand exactly how robots work. Until recently we’ve been able to write this off as science fiction stuff, because real robots were boring industrial arms and anything else was fictional. However, since 2010, robots have been rolling out into the real world in a whole range of shapes, characters and notably, stereotypes. My original research on the naming of robots gave some indications as to just how insidious this human tendency to anthropomorphize and gender robots really is. Now we’re starting to face the consequences and it matters.

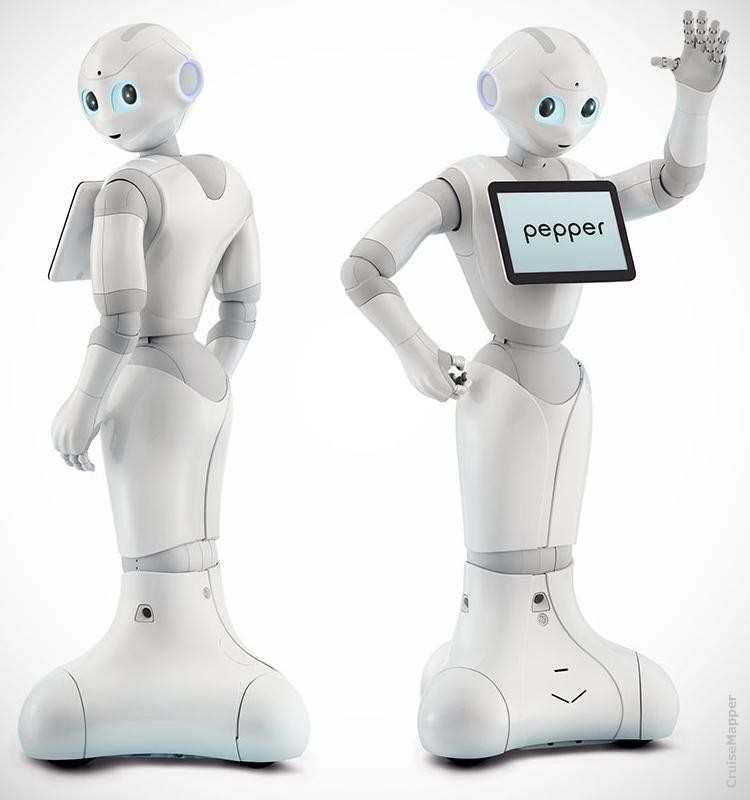

Firstly, let’s consider that many languages have gendered nouns, so there is a preliminary linguistic layer of labelling, ahead of the naming of robots, which if not defined, then tends to happen informally. The founders of two different robot companies have told me that they know when their robot has been accepted in a workplace by when it’s been named by teammates, and they deliberately leave the robot unnamed. Whereas some other companies focus on a more nuanced brand name such as Pepper or Relay, which can minimize gender stereotypes, but even then the effects persist.

Because with robots the physical appearance can’t be ignored and often aligns with ideas of gender. Next, there is the robot voice. Then, there are other layers of operation which can affect both a robot’s learning and its response. And finally, there is the robot’s task or occupation and its socio-cultural context.

Names are both informative and performative. We can usually ascribe a gender to a named object. Similarly, we can ascribe gender based on a robot’s appearance or voice, although it can differ in socio-cultural contexts.

The robot Pepper was designed to be a childlike humanoid and according to SoftBank Robotics, Pepper is gender neutral. But in general, I’ve found that US people tend to see Pepper as female helper, while Asian people are more likely to see Pepper as a boy robot helper. This probably has something to do with the popularity of Astro Boy (Mighty Atom) from 1952 to 1968.

One of the significant issues with gendering robots is that once embodied, individuals are unlikely to have the power to change the robot that they interact with. Even if they rename it, recostume it and change the voice, the residual gender markers will be pervasive and ‘neutral’ will still elicit a gender response in everybody.

This will have an impact on how we treat and trust robots. This also has much deeper social implications for all of us, not just those who interact with robots, as robots are recreating all of our existing gender biases. And once the literal die is cast and robots are rolling out of a factory, it will be very hard to subsequently change the robot body.

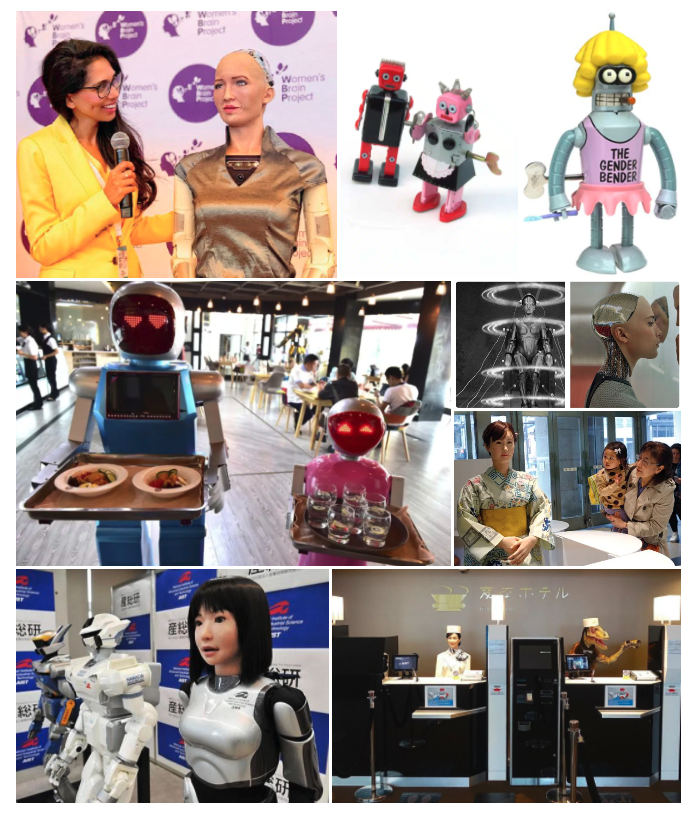

Interestingly, I’m noticing a transition from a default male style of robot (think of all the small humanoid fighting, dancing and soccer playing robots) to a default female style of robot as the service robotics industry starts to grow. Even when the robot is simply a box shape on wheels, the use of voice can completely change our perception. One of the pioneering service robots from Savioke, Relay, deliberately preselected a neutral name for their robot and avoided using a human voice completely. Relay makes sounds but doesn’t use words. Just like R2D2, Relay expresses character through beeps and boops. This was a conscious, and significant, design choice for Savioke. Their preliminary experimentation on human-robot interaction showed that robots that spoke were expected to answer questions, and perform tasks at a higher level of competency than a robot that beeped.

Relay from Savioke delivering at Aloft Hotel

Not only did Savioke remove the cognitive dissonance of having a robot seem more human that it really is, but they removed some of the reiterative stereotyping that is starting to occur with less thoughtful robot deployments. The best practice for designing robots for real world interaction is to minimize human expressivity and remove any gender markers. (more about that next).

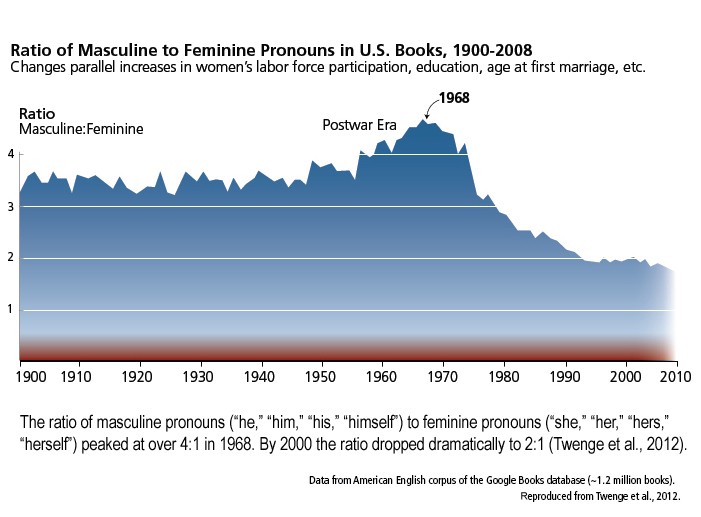

The concept of ‘marked’ and ‘unmarked’ arose in linguistics in the 1930s, but we’ve seen it play out in Natural Language Processing, search and deep learning repeatedly since then, perpetuating, reiterating and exaggerating the use of masculine terminology as the default, and feminine terminology used only in explicit (or marked) circumstances. Marked circumstances almost always relate to sexual characteristics or inferiority within power dynamics, rather than anything more interesting.

An example of unmarked or default terminology is the use of ‘man’ to describe people, but ‘woman’ to only describe a subset of ‘man’. This is also commonly seen in the use of a female specifier on a profession, ie. female police officer, female president, or female doctor. Otherwise, in spite of there being many female doctors, the search will return male examples, call female doctors he, or miscategorize them as nurse. We are all familiar with those mistakes in real life but had developed social policies to reduce the frequency of them. Now AI and robotics are bringing the stereotype back.

And so it happens that the ‘neutral’ physical appearance of robots is usually assumed to be male, rather than female, unless the robot has explicit female features. Sadly, female robots mean either a sexualized robot, or a robot performing a stereotypically female role. This is how people actually see and receive robots unless a company, like Savioke, consciously refrains from triggering our stereotypically gendered responses.

I can vouch for the fact that searching for images using the term “female roboticists”, for example, always presents me with lots of men building female robots instead. It will take a concerted effort to change things. Robot builders have the tendency to give our robots character. And unless you happen to be a very good (and rich) robotics company, there is also no financial incentive to degender robots. Quite the opposite. There is financial pressure to take advantage of our inherent anthropomorphism and gender stereotypes.

In The Media Equation in 1996, Clifford Reeves and Byron Nass demonstrated how we all attributed character, including gender, to our computing machines, and that this then affected our thoughts and actions, even though most people consciously deny conflating a computer with a personality. This unconscious anthropomorphizing can be used to make us respond differently, so of course robot builders will increasingly utilize the effect as more robots enter society and competition increases.

Can human beings relate to computer or television programs in the same way they relate to other human beings? Based on numerous psychological studies, this book concludes that people not only can but do treat computers, televisions, and new media as real people and places. Studies demonstrate that people are “polite” to computers; that they treat computers with female voices differently than “male” ones; that large faces on a screen can invade our personal space; and that on-screen and real-life motion can provoke the same physical responses.

The Media Equation

The history of voice assistants shows a sad trend. These days, they are all female, with the exception of IBM Watson, but then Watson occupies a different ecosystem niche. Watson is an expert. Watson is the doctor to the rest of our subservient, map reading, shopping list helpful nurses. By default, unless you’re in Arabia, your voice assistant device will have a female voice. You have to go through quite a few steps to consciously change it and there are very few options. In 2019, Q, a genderless voice assistant was introduced, however I can’t find it offered on any devices yet.

And while it may be possible to upload a different voice to a robot, there’s nothing we can do if the physical design of the robot evokes gender. Alan Winfield wrote a very good article “Should robots be gendered?” here on Robohub in 2016, in which he outlines three reasons that gendered robots are a bad idea, all stemming from the 4th of the EPSRC Principles of Robotics, that robots should be transparent in action, rather than capitalizing on the illusion of character, so as not to influence vulnerable people.

Robots are manufactured artefacts: the illusion of emotions and intent should not be used to exploit vulnerable users.

My biggest quibble with the EPSRC Principles is underestimating the size of the problem. By stating that vulnerable users are the young or the elderly, the principles imply that the rest of us are immune from emotional reaction to robots, whereas Reeves and Nass clearly show the opposite. We are all easily manipulated by our digital voice and robot assistants. And while Winfield recognizes that gender queues are powerful enough to elicit a response in everybody, he only sees the explicit gender markers rather than understanding that unmarked or neutral seeming robots also elicit a gendered response, as ‘not female’.

So Winfield’s first concern is emotional manipulation for vulnerable users (all of us!), his second concern is anthropomorphism inducing cognitive dissonance (over promising and under delivering), and his final concern is that the all the negative stereotypes contributing to sexism will be reproduced and reiterated as normal through the introduction of gendered robots in stereotyped roles (it’s happening!). These are all valid concerns, and yet while we’re just waking up to the problem, the service robot industry is growing by more than 30% per annum.

Where the growth of the industrial robotics segment is comparatively predictable, the world’s most trusted robotics statistics body, the International Federation of Robotics is consistently underestimating the growth of the service robotics industry. In 2016, the IFR predicted 10% growth for professional service robotics over the next few years from \$4.6 Billion, but by 2018 they were recording 61% growth to \$12.6B and by 2020 the IFR has recorded 85% overall growth expecting revenue from service robotics to hit \$37B by 2021.

It’s unlikely that we’ll recall robots, once designed, built and deployed, for anything other than a physical safety issue. And the gendering of robots isn’t something we can roll out a software update to fix. We need to start requesting companies to not deploy robots that reinforce gender stereotyping. They can still be cute and lovable, I’m not opposed to the R2D2 robot stereotype!

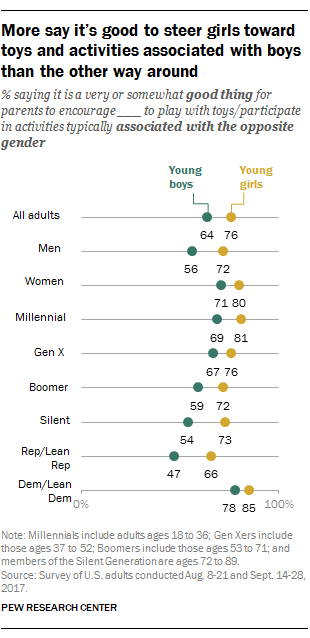

Consumers are starting to fight back against the gender stereotyping of toys, which really only started in the 20th century as a way to extract more money from parents, and some brands are realizing that there’s an opportunity for them in developing gender neutral toys. Recent research from the Pew Research Center found that overall 64% of US adults wanted boys to play with toys associated with girls, and 76% of US adults wanted girls to play with toys associated with boys. The difference between girls and boys can be explained because girls’ role playing (caring and nurturing) is still seen as more negative than boys’ roles (fighting and leadership). But the overall range that shows that society has developed a real desire to avoid gender stereotyping completely.

Sadly, it’s like knowing sugar is bad for us, while it still tastes sweet.

In 2016, I debated Ben Goertzel, maker of Sophia the Robot, on the main stage of the Web Summit on whether humanoid robots were good or bad. I believe I made the better case in terms of argument, but ultimately the crowd sided with Goertzel, and by default with Sophia. (there are a couple of descriptions of the debate referenced below).

Robots are still bright shiny new toys to us. When are we going to realize that we’ve already opened the box and played this game, and women, or any underrepresented group, or any stereotype role, is going to be the loser. No, we’re all going to lose! Because we don’t want these stereotypes any more and robots are just going to reinforce the stereotypes that we already know we don’t want.

And did I mention how white all the robots are? Yes, they are racially stereotyped too. (See Ayanna Howard’s new book “Sex, Race and Robots: How to be human in an age of AI”)

References:

- https://robohub.org/robots-should-not-be-gendered/

- https://genderedinnovations.stanford.edu/case-studies/nlp.html

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/37705092_The_Media_Equation_How_People_Treat_Computers_Television_and_New_Media_Like_Real_People_and_Pla

- https://www.wsj.com/articles/alexa-siri-cortana-the-problem-with-all-female-digital-assistants-1487709068

- https://en.unesco.org/Id-blush-if-I-could

- https://epsrc.ukri.org/research/ourportfolio/themes/engineering/activities/principlesofrobotics/

- https://transmitter.ieee.org/web-summit-debate-robots-people/

- https://medium.com/@kyecass/should-robots-look-and-act-like-humans-35790e8005b3

- https://cristinaturbatu.wordpress.com/2016/11/16/web-summit-lisbon-2016/

- https://www.therobotreport.com/ifrs-two-reports-for-2015-show-double-digit-growth-for-remainder-of-decade/

- https://www.roboticsbusinessreview.com/research/world-robotics-report-global-sales-of-robots-hit-16-5b-in-2018/

- https://www.robotics.org/service-robots/what-are-professional-service-robots

- https://theconversation.com/how-toys-became-gendered-and-why-itll-take-more-than-a-gender-neutral-doll-to-change-how-boys-perceive-femininity-124386

- https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/12/19/most-americans-see-value-in-steering-children-toward-toys-activities-associated-with-opposite-gender/

- https://observer.com/2019/08/robot-racial-bias-study/

- https://www.marketplace.org/shows/marketplace-tech/should-robots-have-gender-or-ethnicity-one-roboticist-says-no-ayanna-howard-sex-race-robots/