Anton Grabolle / Autonomous Driving / Licenced by CC-BY 4.0

Anton Grabolle / Autonomous Driving / Licenced by CC-BY 4.0

By Susan Kelley

Autonomous vehicles (AVs) have been tested as taxis for decades in San Francisco, Pittsburgh and around the world, and trucking companies have enormous incentives to adopt them.

But AV companies rarely share the crash- and safety-related data that is crucial to improving the safety of their vehicles – mostly because they have little incentive to do so.

Is AV safety data an auto company’s intellectual asset or a public good? It can be both – with a little tweaking, according to a team of Cornell researchers.

The team has created a roadmap outlining the barriers and opportunities to encourage AV companies to share the data to make AVs safer, from untangling public versus private data knowledge, to regulations to creating incentive programs.

“The core of AV market competition involves who has that crash data, because once you have that data, it’s much easier for you to train your AI to not make that error. The hope is to first make this data transparent and then use it for public good, and not just profit,” said Hauke Sandhaus, M.S. ’24, a doctoral candidate at Cornell Tech and co-author of “My Precious Crash Data,” published Oct. 16 in ACM on Human-Computer Interaction and presented at the ACM SIGCHI Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing.

His co-authors are Qian Yang, assistant professor at the Cornell Ann S. Bowers College of Computing and Information Science; Wendy Ju, associate professor of information science and design tech at Cornell Tech, the Cornell Ann S. Bowers College of Computing and Information Science and the Jacobs Technion-Cornell Institute; and Angel Hsing-Chi Hwang, a former postdoctoral associate at Cornell and now assistant professor of communication at the University of Southern California, Annenberg.

The team interviewed 12 AV company employees who work on safety in AV design and deployment, to understand how they currently manage and share safety data, the data sharing challenges and concerns they face, and their ideal data-sharing practices.

The interviews revealed the AV companies have a surprising diversity of approaches, Sandhaus said. “Everyone really has some niche, homegrown data set, and there’s really not a lot of shared knowledge between these companies,” he said. “I expected there would be much more commonality.”

The research team discovered two key barriers to sharing data – both underscoring a lack of incentives. First, crash and safety data includes information about the machine-learning models and infrastructure that the company uses to improve safety. “Data sharing, even within a company, is political and fraught,” the team wrote in the paper. Second, the interviewees believed AV safety knowledge is private and brings their company a competitive edge. “This perspective leads them to view safety knowledge embedded in data as a contested space rather than public knowledge for social good,” the team wrote.

And U.S. and European regulations are not helping. They require only information such as the month when the crash occurred, the manufacturer and whether there were injuries. That doesn’t capture the underlying unexpected factors that often cause accidents, such as a person suddenly running onto the street, drivers violating traffic rules, extreme weather conditions or lost cargo blocking the road.

To encourage more data-sharing, it’s crucial to untangle safety knowledge from proprietary data, the researchers said. For example, AV companies could share information about the accident, but not raw video footage that would reveal the company’s technical infrastructure.

Companies could also come up with “exam questions” that AVs would have to pass in order to take the road. “If you have pedestrians coming from one side and vehicles from the other side, then you can use that as a test case that other AVs also have to pass,” Sandhaus said.

Academic institutions could act as data intermediaries with which AV companies could leverage strategic collaborations. Independent research institutions and other civic organizations have set precedents working with industry partners’ public knowledge. “There are arrangements, collaboration, patterns for higher ed to contribute to this without necessarily making the entire data set public,” Qian said.

The team also proposes standardizing AV safety assessment via more effective government regulations. For example, a federal policymaking agency could create a virtual city as a testing ground, with busy traffic intersections and pedestrian-heavy roads that every AV algorithm would have to be able to navigate, she said.

Federal regulators could encourage car companies to contribute scenarios to the testing environment. “The AV companies might say, ‘I want to put my test cases there, because my car probably has passed those tests.’ That can be a mechanism for encouraging safer vehicle development,” Yang said. “Proposing policy changes always feels a little bit distant, but I do think there are near-future policy solutions in this space.”

The research was funded by the National Science Foundation and Schmidt Sciences.

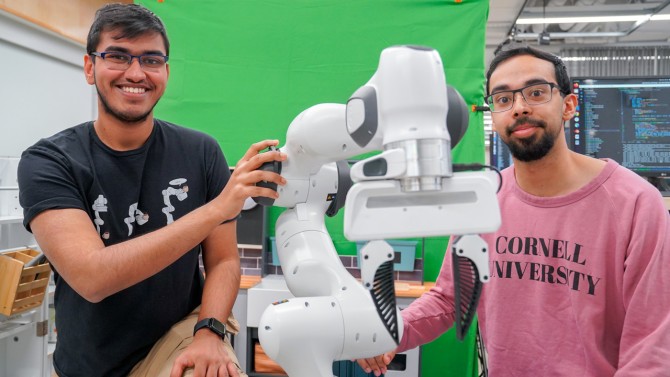

Kushal Kedia (left) and Prithwish Dan (right) are members of the development team behind RHyME, a system that allows robots to learn tasks by watching a single how-to video.

Kushal Kedia (left) and Prithwish Dan (right) are members of the development team behind RHyME, a system that allows robots to learn tasks by watching a single how-to video.