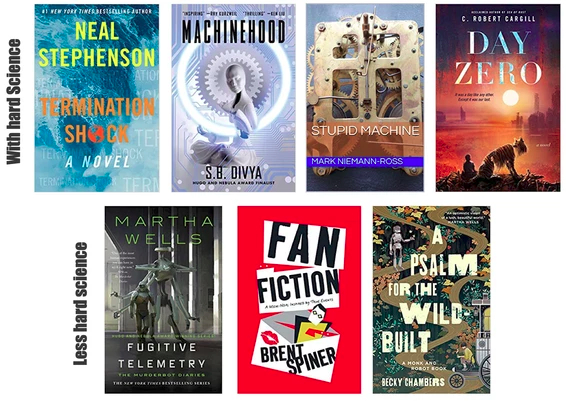

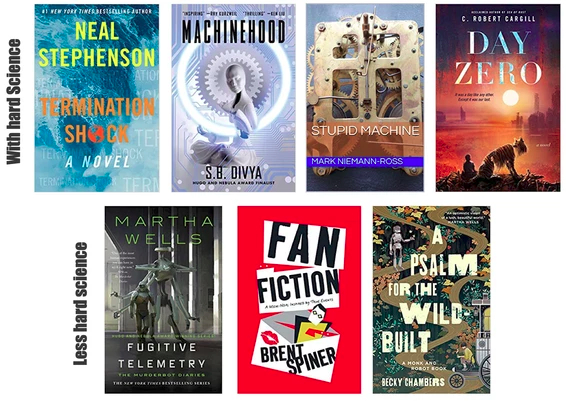

Scifi robot books of 2021

2021 produced four new scifi books with good hard science underpinning their description of robots and three where there was less science but lots of interesting ideas about robots. Not only are these books enjoyable on their own, fiction can serve as teachable moments in robots and STEM and inspire a robot-obsessed teen to read more and improve their reading comprehension.

- Termination Shock

- Machinehood

- Stupid Machine

- Day Zero

- Fugitive Telemetry

- Fan Fiction

- A Psalm for the Wild-Built

Let’s start with the scifi book I most frequently recommended to friends to read in 2021: Termination Shock by Neal Stephenson. It is not a robot book per se but robots and automation are realistically interspersed through it- and the book is one of Stephenson’s best, pulling together LOTS of technology, subplots, and themes similar to what he did in Diamond Age. One of the technology threads is how drones are ubiquitous throughout the book, with small drones being used singly or in swarms for surveillance and social media and bigger drones used for delivery, human transport, and, well, mayhem. Nominally the book is about climate change and how a group of individuals led by a rich Texan plan to cut through the COP26 meetings blather and get on with geoengineering the environment. Except money and geoengineering is the easy part… It’s a dramedy of a book and manages to never lecture or push political agendas, instead it is hard science wrapped with memorable characters, a compelling plot, and a sense of humor, with an “oh my!” twist at the end.

A great way to think about how drones are becoming subtly integrated as tools into military, security, and journalism. And that at the end of the day, despite the huge investment in anti-drone technology, a shotgun with bird shot may be our best defense for small drones. Check out the RTSF topics page for more links to the science.

Unlike Termination Shock, robots and AI *are* the subject of S.B. Divya’s Machinehood. It’s a thorny book with a piercingly sharp commentary on the gig economy, climate change, automation, and ethics. A rogue neo-Buddhist decides that intelligent machines deserve legal rights and protections, similar to animals, which she calls the Machinehood Manifesto. Then she leads a terrorist cell to force governments to incorporate machinehood protections into their legal framework. A SpecialOps operator is tasked to take her down, which she does with the help of her sister-in-law. Lots of action, lots of ideas, lots of realism and full of thought provoking jabs. The book echoes real-world arguments since the 1980’s about treating robots as animals from a legal perspective.

It is a wonderful, very useful introduction to issues in robot ethics and autonomy and the very real concept of treating robots like animals- which is covered in the non-fiction book The New Breed by Kate Darling. You can read more about that in my recent Science Robotics article.

Stupid Machine by Mark Niemann-Ross is a comedy with an interesting and timely plot about autonomous cars, cyber hackers, and social justice warriors in Portland. It would be tempting to hack an autonomous car to drive an annoying semi-full time, I-protest-everything activist off a bridge, wouldn’t it? Plus there is a nice Ubik-like smart house subplot. Not as well-written, plotted, and memorable as Termination Shock and Machinehood, but a quick, easy read.

The idea that autonomous cars will be both ubiquitous and hackable makes it a nice teachable moment about cybersecurity. A recent scifi book that explains more about the workings of autonomous driving is David Walton’s There Laws Lethal. You can read my Science Robotics article on autonomous cars in scifi here.

Like Machinehood, Day Zero by C. Robert Cargill is set a near future. It’s the prequel to Sea of Rust, one of my all time favorite robot scifi books. Sea of Rust is an evocative story about what happens after the robot revolution and how the robots themselves descend into a kind of Mad Max hell. Day Zero isn’t as striking as Sea of Rust, but very enjoyable as a prequel. If you loved Spielberg’s AI: Artificial Intelligence, then you’ll doubly love Day Zero because it is told from the POV of Pounce, the Teddy-like robot, who protects his boy Ezra during the robot revolution. You don’t have to read Sea of Rust first, Day Zero is a stand alone, but I recommend you do. I hope there are more books in the Sea of Rust series.!

In terms of robotics, Day Zero is a good introduction to nursebots, healthcare robots, and domestic assistance robots. You can learn more about the science of nannybots at the Science Robotics article and domestic robotics, sometimes called domotics at Science Robotics here.

Of course, there was a lot of other robot science fiction in 2021, just with less science. Here are three books for you to consider that have some robots in with real world science.

The Murderbot Diaries by Martha Wells is one of my top “you’ve got to read!” The latest addition, Fugitive Telemetry, continues the delightful Bildungsroman of the galaxy’s snarkiest robot. ROFL as always, it maintains the usual clever plotting and action that makes the Murderbot Diaries a favorite of both the Hugos and Nebulas awards. And Murderbot, like the humans in Termination Shock, has a swarm of drones and knows how to use them. Oh, SecUnit, I love you!

And I love the series as way of illustrating real-world problems in software engineering and cybersecurity for robotics. Check out the discussions of software engineering in the first book and the Internet of Things in the fourth.

It’s hard not to like Lieutenant Commander Data on Star Trek and Picard, right? Well, it’s hard not to like Brent Spiner, the nice Jewish boy from Houston who grew up to write a funny, self-mocking semi-fictional autobiography as well as star in a hit TV series. He calls his book, Fan Fiction, a “mem-noir” where an actor, conveniently named Brent Spiner, on the third season of a modest hit conveniently called “ST:TNG” is being stalked by a someone purported to be Lal, Data’s short-lived robot daughter. The hapless actor finds it is as if he is living in a Raymond Chandler novel. Brent reflects on his life and how he got to this point in his career as he tries to go about shooting episodes, going to parties at the Roddenberrys, signing autographs at cons, and hanging out with Patrick Stewart, Levar Burton, and Jonathan Frakes. Yet Spiner comes across as a regular guy, grounded and grateful- and amused- at “making it” in Hollywood. It makes me long for a follow up- what was life for that actor after the years of grueling 16 hour days on set and the increasing fame?

OK, there is not much there in terms of teachable moments about robots, but it is still fun.

A Psalm for the Wild-Built by Becky Chambers, the reigning comfort lit scifi writer (and that’s a good thing!), is a sentimental Solar-punk book. The book doesn’t have a lot of action but could be perfect for middle schoolers (though some f-bombs are dropped) or a read-aloud to younger children. Or something to just to enjoy instead of listening to Lake Woebegone tales or re-reading Cadfael books. The premise is that in a future world, robots spontaneously gained sentience and then left human occupied terrorizes to explore being a robot. Now they are back, self-actualized, and ready to explore humanity by asking “what do humans need?”

Doesn’t sound like there’s much about real robots, does it? And yet, it has one of the most cogent explanations of agency, of what makes something more than a machine, which is a fundamental concept in artificial intelligence and in how autonomy is different than automation.

Hopefully this list of books gives you something to read and, more importantly, something to think about in 2022!