Prototype robotic dogs built by Texas A&M University engineering students and powered by artificial intelligence demonstrate their advanced navigation capabilities. Photo credit: Logan Jinks/Texas A&M University College of Engineering.

Prototype robotic dogs built by Texas A&M University engineering students and powered by artificial intelligence demonstrate their advanced navigation capabilities. Photo credit: Logan Jinks/Texas A&M University College of Engineering.

By Jennifer Nichols

Meet the robotic dog with a memory like an elephant and the instincts of a seasoned first responder.

Developed by Texas A&M University engineering students, this AI-powered robotic dog doesn’t just follow commands. Designed to navigate chaos with precision, the robot could help revolutionize search-and-rescue missions, disaster response and many other emergency operations.

Sandun Vitharana, an engineering technology master’s student, and Sanjaya Mallikarachchi, an interdisciplinary engineering doctoral student, spearheaded the invention of the robotic dog. It can process voice commands and uses AI and camera input to perform path planning and identify objects.

A roboticist would describe it as a terrestrial robot that uses a memory-driven navigation system powered by a multimodal large language model (MLLM). This system interprets visual inputs and generates routing decisions, integrating environmental image capture, high-level reasoning, and path optimization, combined with a hybrid control architecture that enables both strategic planning and real-time adjustments.

A pair of robotic dogs with the ability to navigate through artificial intelligence climb concrete obstacles during a demonstration of their capabilities. Photo credit: Logan Jinks/Texas A&M University College of Engineering.

A pair of robotic dogs with the ability to navigate through artificial intelligence climb concrete obstacles during a demonstration of their capabilities. Photo credit: Logan Jinks/Texas A&M University College of Engineering.

Robot navigation has evolved from simple landmark-based methods to complex computational systems integrating various sensory sources. However, navigating in unpredictable and unstructured environments like disaster zones or remote areas has remained difficult in autonomous exploration, where efficiency and adaptability are critical.

While robot dogs and large language model-based navigation exist in different contexts, it is a unique concept to combine a custom MLLM with a visual memory-based system, especially in a general-purpose and modular framework.

“Some academic and commercial systems have integrated language or vision models into robotics,” said Vitharana. “However, we haven’t seen an approach that leverages MLLM-based memory navigation in the structured way we describe, especially with custom pseudocode guiding decision logic.”

Mallikarachchi and Vitharana began by exploring how an MLLM could interpret visual data from a camera in a robotic system. With support from the National Science Foundation, they combined this idea with voice commands to build a natural and intuitive system to show how vision, memory and language can come together interactively. The robot can quickly respond to avoid a collision and handles high-level planning by using the custom MLLM to analyze its current view and plan how best to proceed.

“Moving forward, this kind of control structure will likely become a common standard for human-like robots,” Mallikarachchi explained.

The robot’s memory-based system allows it to recall and reuse previously traveled paths, making navigation more efficient by reducing repeated exploration. This ability is critical in search-and-rescue missions, especially in unmapped areas and GPS-denied environments.

The potential applications could extend well beyond emergency response. Hospitals, warehouses and other large facilities could use the robots to improve efficiency. Its advanced navigation system might also assist people with visual impairments, explore minefields or perform reconnaissance in hazardous areas.

Nuralem Abizov, Amanzhol Bektemessov and Aidos Ibrayev from Kazakhstan’s International Engineering and Technological University developed the ROS2 infrastructure for the project. HG Chamika Wijayagrahi from the UK’s Coventry University supported the map design and the analysis of experimental results.

Vitharana and Mallikarachchi presented the robot and demonstrated its capabilities at the recent 22nd International Conference on Ubiquitous Robots. The research was published in A Walk to Remember: MLLM Memory-Driven Visual Navigation.

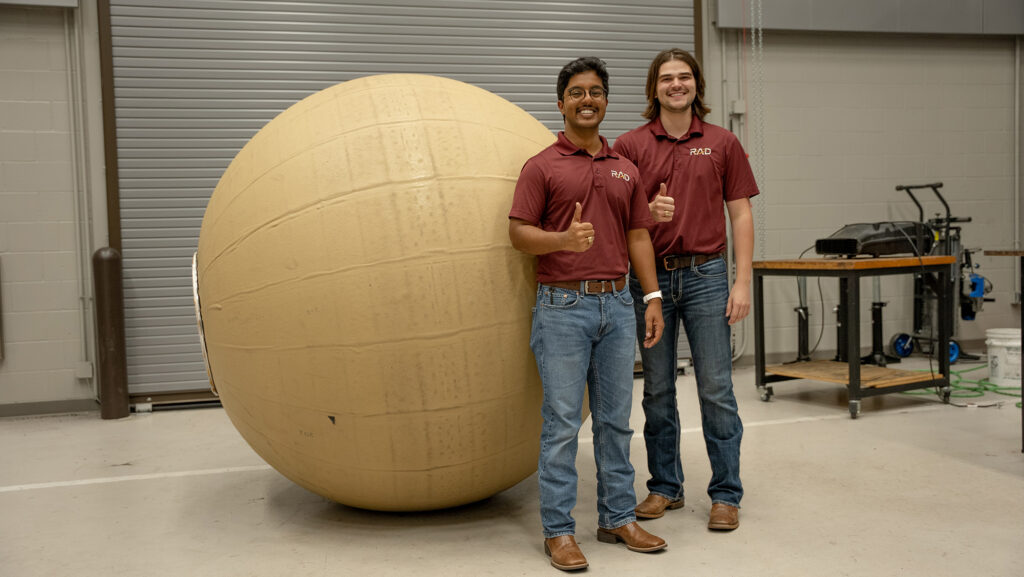

Rishi Jangale and Derek Pravecek with RoboBall III. Image credit: Emily Oswald/Texas A&M Engineering.

Rishi Jangale and Derek Pravecek with RoboBall III. Image credit: Emily Oswald/Texas A&M Engineering.