If you had asked Adama Sesay as a child what she wanted to be when she grew up, the answer would have been a doctor, an architect, and a firefighter. Now a Senior Engineer specializing in sensors and microsystems, you may think she’s gone in a completely different direction, but by following the passions that led her to those ideas – science, design, and saving lives – she’s found a career she loves. At the Wyss, Adama is a member of the Advanced Technology Team and works on a wide range of projects that span from sensor-integrated Organ Chips to make drugs safer to an enzyme that converts sugar to fiber to make food healthier, while simultaneously leading the Women’s Health Catalyst. Learn more about Adama and her work in this month’s Humans of the Wyss.

What projects are you involved with?

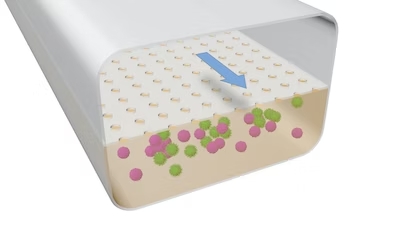

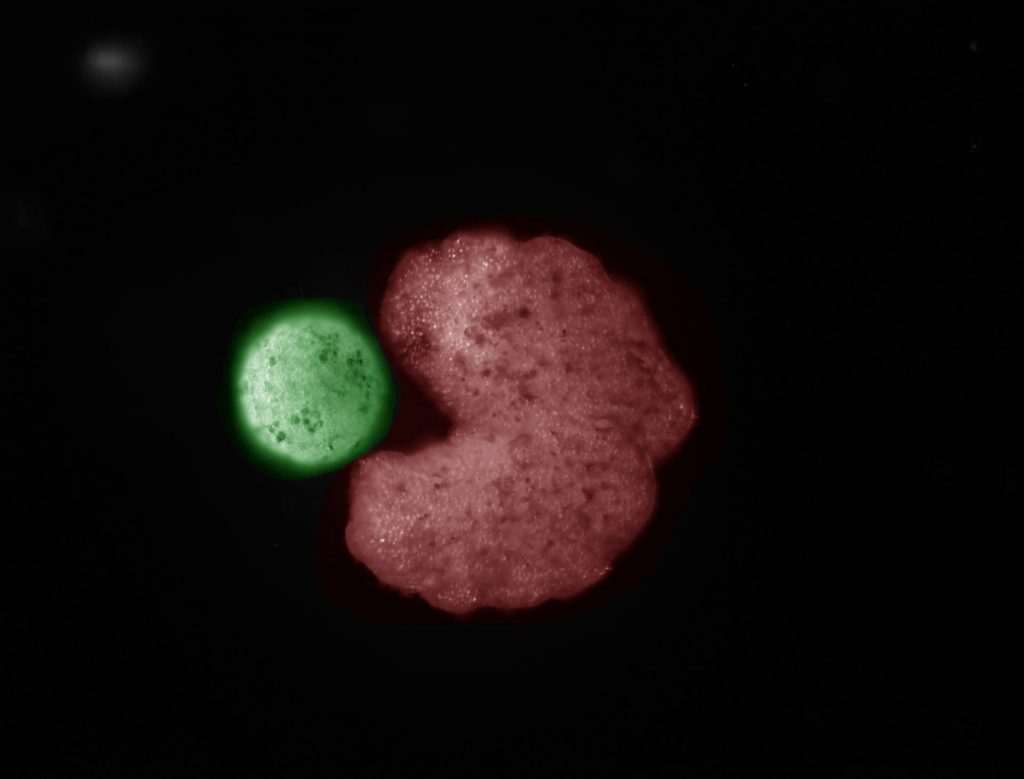

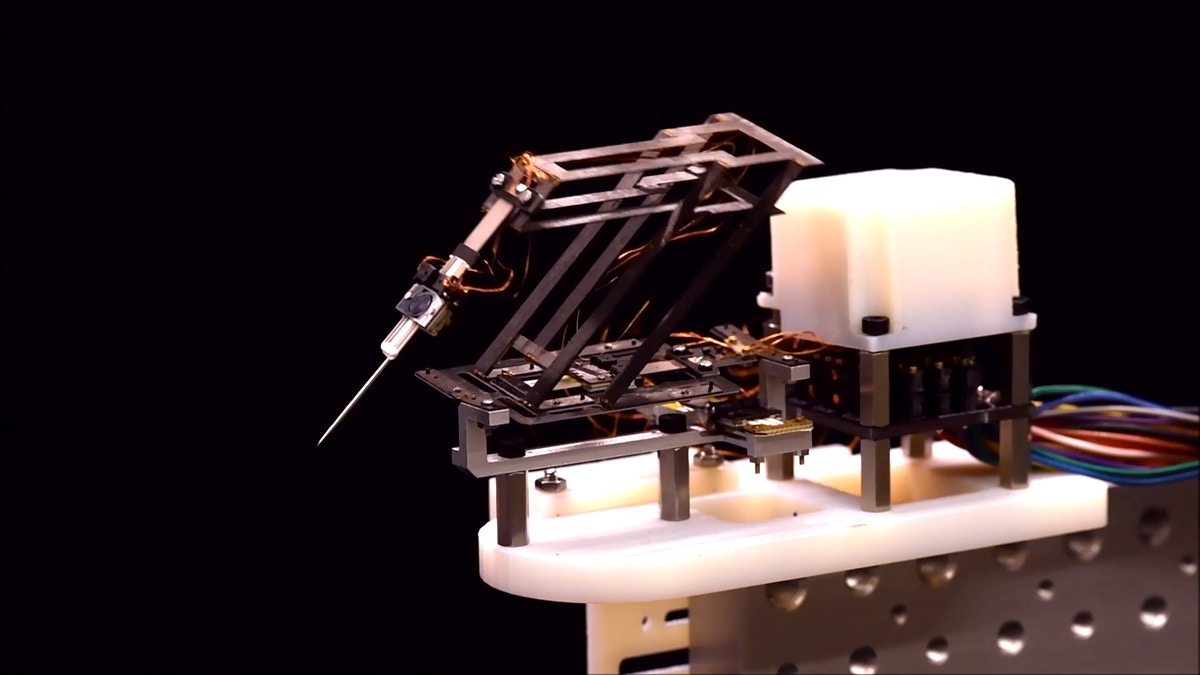

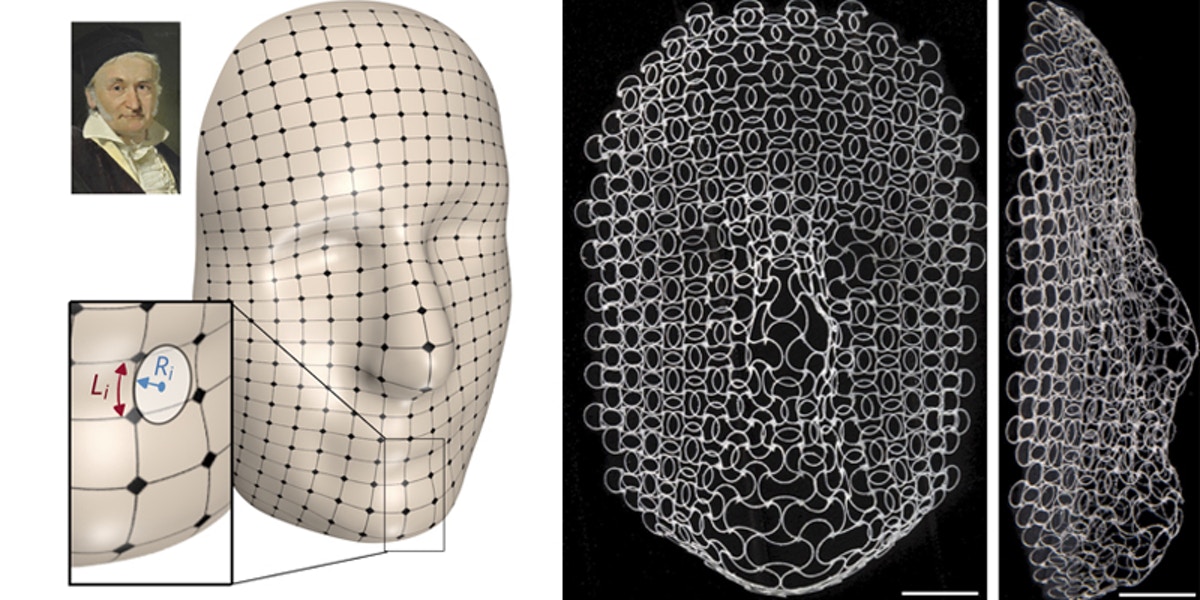

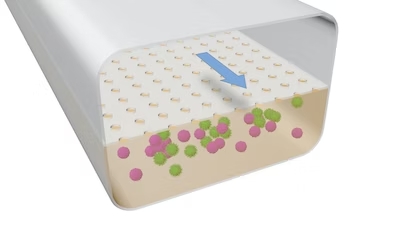

I specialize in biosensing, microfluidics, and microsystems, and my projects span over quite a diverse area. The first project I’ve been managing is a BARDA project, which is a federally funded project looking at integrating sensors to measure biomarkers like cytokines, from a lymph node tissue model, or a lymphoid follicle (LF) Chip. In this project, I’ve mostly concentrated on the instrumentation side, providing the actual hardware (which is a sort of sensor-integrated cartridge) and retrofitting it into a commercial Organ Chip system.

Adama Sesay, Senior Engineer II. Credit: Wyss Institute at Harvard University

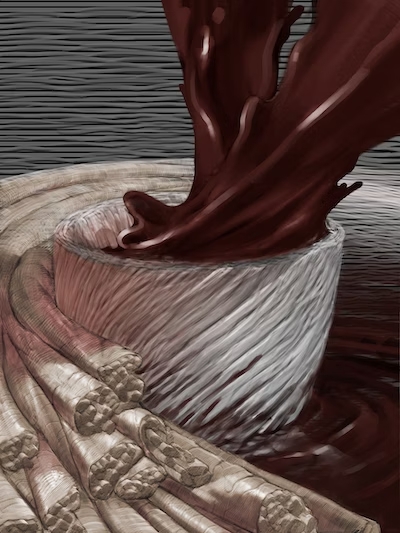

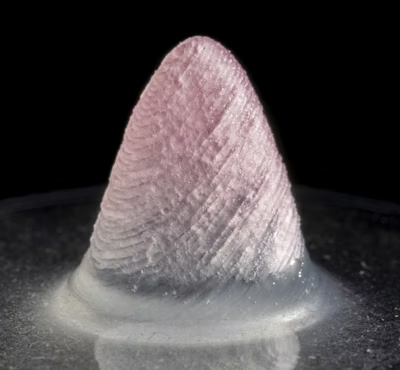

Then I have another project where we’re developing an enzyme-encapsulated particle that reduces sugar in food once it’s consumed, converting it to dietary fiber. Basically, this would be a “smart food” ingredient, where the enzyme is only activated once you consume it. That way, the food tastes the same, but the actual amount of sugar your body metabolizes is lower.

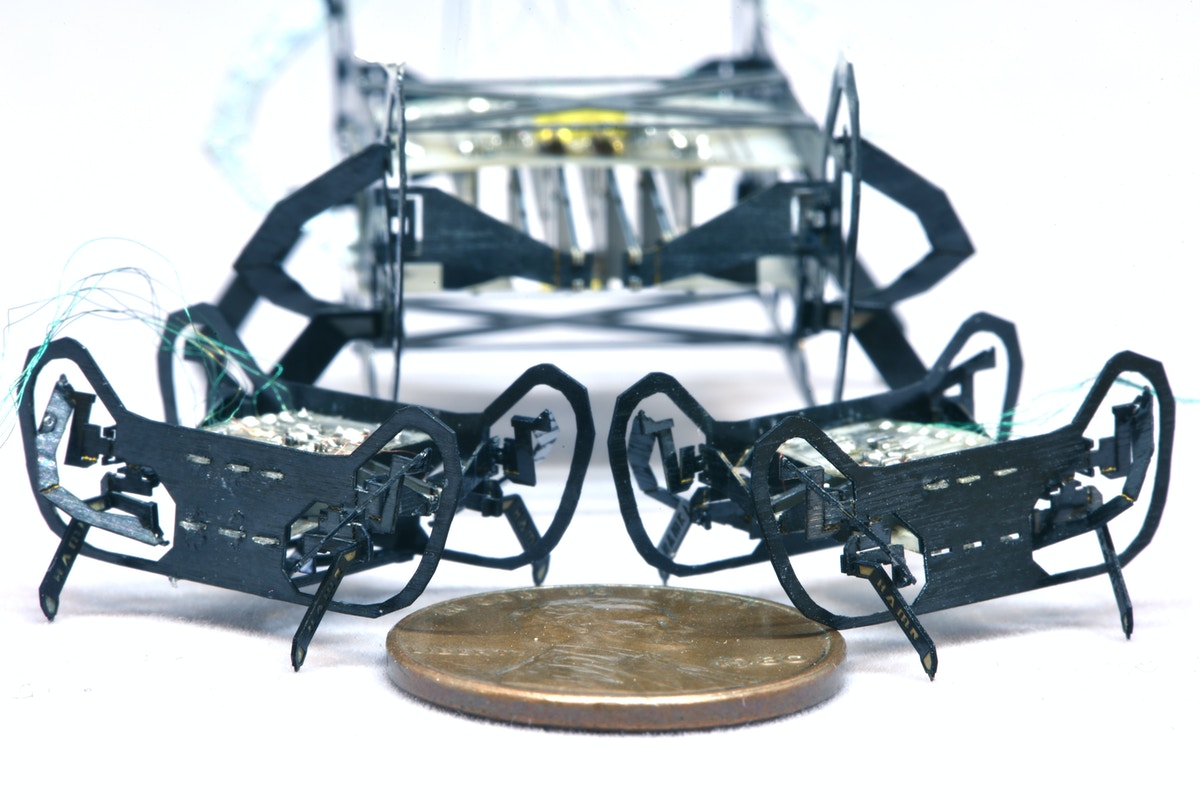

I’m working on a third project where we are developing and microfabricating a microfluidic Blood Clotting Chip to study clotting time for patients that have mesothelioma, a cancer caused by exposure to asbestos. We’re collaborating with Massachusetts General Hospital and Boston Children’s Hospital.

What are biosensors, microfluidics, and microsystems?

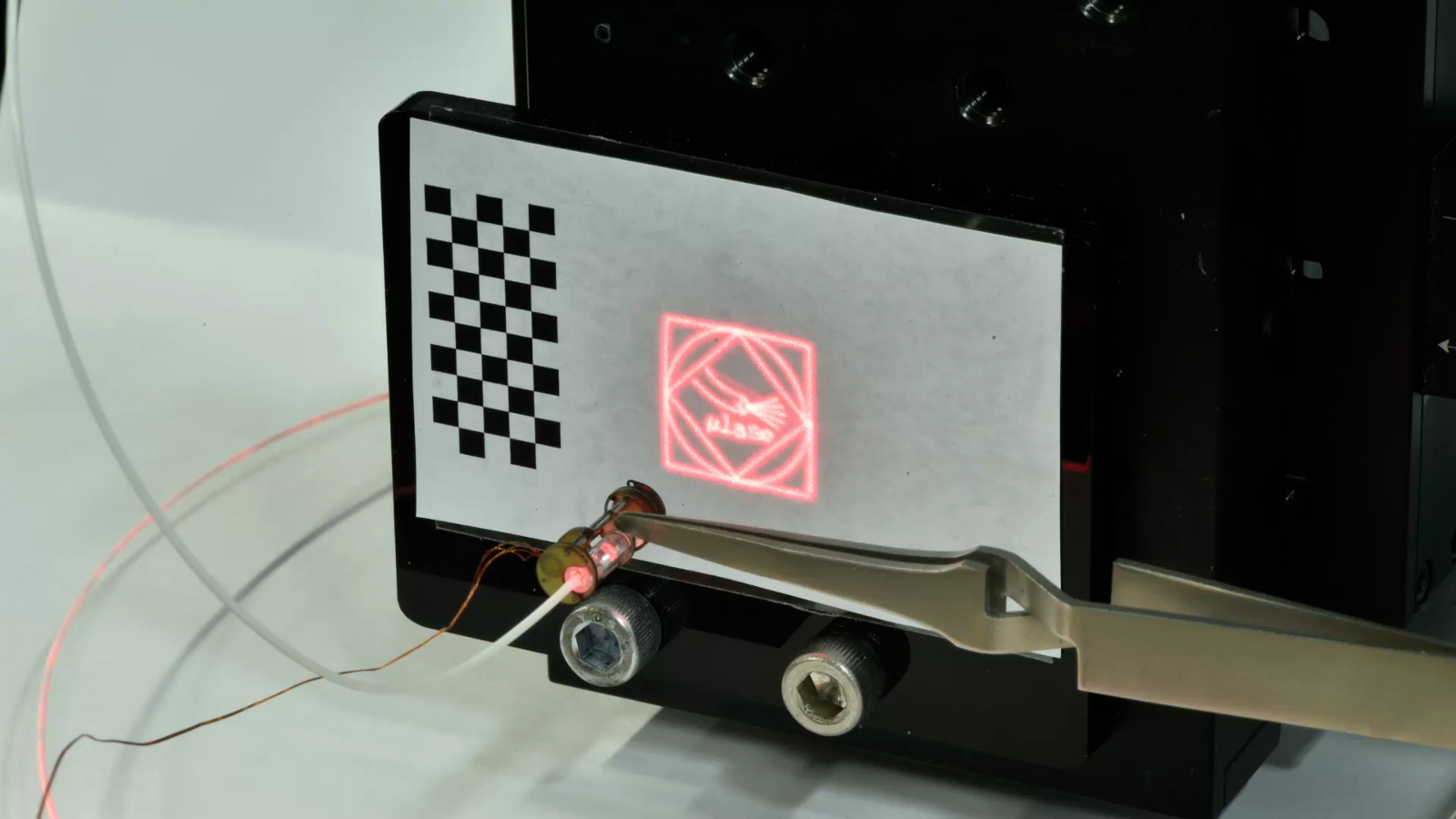

A biosensor is a device that combines a biological component with a sensor transducer and can measure a biological or chemical reaction by producing signals to indicate the concentration of the analyte, or component of interest, in the monitored sample. Microfluidics refers to a system that has small channels that can move and deliver low volumes of fluid. The concept is that fabrication-wise, a microfluidic channel is anything that has dimensions in the micrometer range. The advantage of microfluidics is that you can deliver very low volumes to different areas and manipulate those flows a classic example is a an Organ Chip. A microsystem device in this context takes it a bit further and is the integration of sensors, microfluidics, and application. The three are a closely integrated package.

What real-world problems do these projects address?

With the BARDA project, we can use the LF Chips to monitor the immune system’s reaction to different types of drugs. We can use patient samples to get time resolved data about the inflammation response. In addition to helping screen drugs for safety, this could help us determine which therapies can be used on immuno-compromised patients or what a vaccine response will be in a certain population.

This illustration demonstrates the structure of the LF Chip that Adama is working on. Credit: Wyss Institute at Harvard University

The sugar fiber project will help address America’s ever-growing problems with obesity and diabetes. Despite these issues, there is a big food industry here that relies on refined sugars, especially high fructose corn syrup. In addition to those other issues, high fructose diets contribute to metabolic syndrome. Plus, the American diet is low in fiber. We started this project looking at how to make food more enjoyable while also being responsible. Our enzyme encapsulation will hopefully address diabetes and metabolic syndrome, while increasing fiber, which will make people’s gut microbiomes healthier.

We hope to use the Blood Clotting Chip to understand the clotting time and the thrombosis factors of mesothelioma. It can also be used as a diagnostic tool. Understanding a patient’s blood clotting factor is essential when they go into surgery, even beyond those suffering from this disease. This became even more apparent to me recently when my father needed to have emergency surgery, but they had to wait until he could be off blood thinners for a period of time. If we could use this as a diagnostic test, surgeons would know when a patient’s clotting factor was such that they were ready for surgery.

What is your specific role on the team?

I’m a Senior Engineer here and part of the Advanced Technology Team, I lead the biosensing, microfluidics, and microsystems effort at the Wyss. I am also responsible for the microfabrication room and efforts, and work closely with Pawan Jolly, who is the lead on sensors. That entails but is not limited to research project management, writing funding proposals, mentorship, and overseeing relationships with internal and external collaborator.

How are you helping to advance women’s health at the Wyss?

One of my biggest interests at the moment is to build up the Women’s Health Catalyst. In a place like the Wyss that’s looking at unmet needs, it’s natural that we have quite a lot of projects already in our pipeline dedicated to women’s health because therapeutics and diagnostics specifically aimed at women’s health issues are one of the biggest unmet clinical needs in the world. All this work is being done within our existing Focus Areas. Many of our researchers are incredibly dedicated to increasing our knowledge and finding real-world solutions.

Adama and the other speakers at the Wyss’ event celebrating Women at the Intersection of Science and Art on International Women’s Day. Credit: Wyss Institute at Harvard University

So, right now we’re aiming to coalesce all these projects to bring together our brilliant scientists, clinicians, and technology teams to advance research and make drugs and devices to help people. We aim to be able to highlight these projects to attract external collaborators to work with our Wyss technology translation engine, and one day become a world-class beacon where people want to come and really make advances in women’s health.

How are you helping to bridge the gap between academia and industry at the Wyss?

I have a diverse group of researchers on my team including biologists, biotechnologists, biomedical engineers, and mechanical engineers who look at challenges very differently, while I look at the industrial need and see how we can translate the science into something to address the gaps. I think what it boils down to is facilitating the communication between scientists and engineers on the research side and translating that acquired knowledge into know-how, services, and products on the business and industrial sides.

“I think what it boils down to is facilitating the communication between scientists and engineers on the research side and translating that acquired knowledge into know-how, services, and products on the business and industrial sides.”

– Adama Sesay

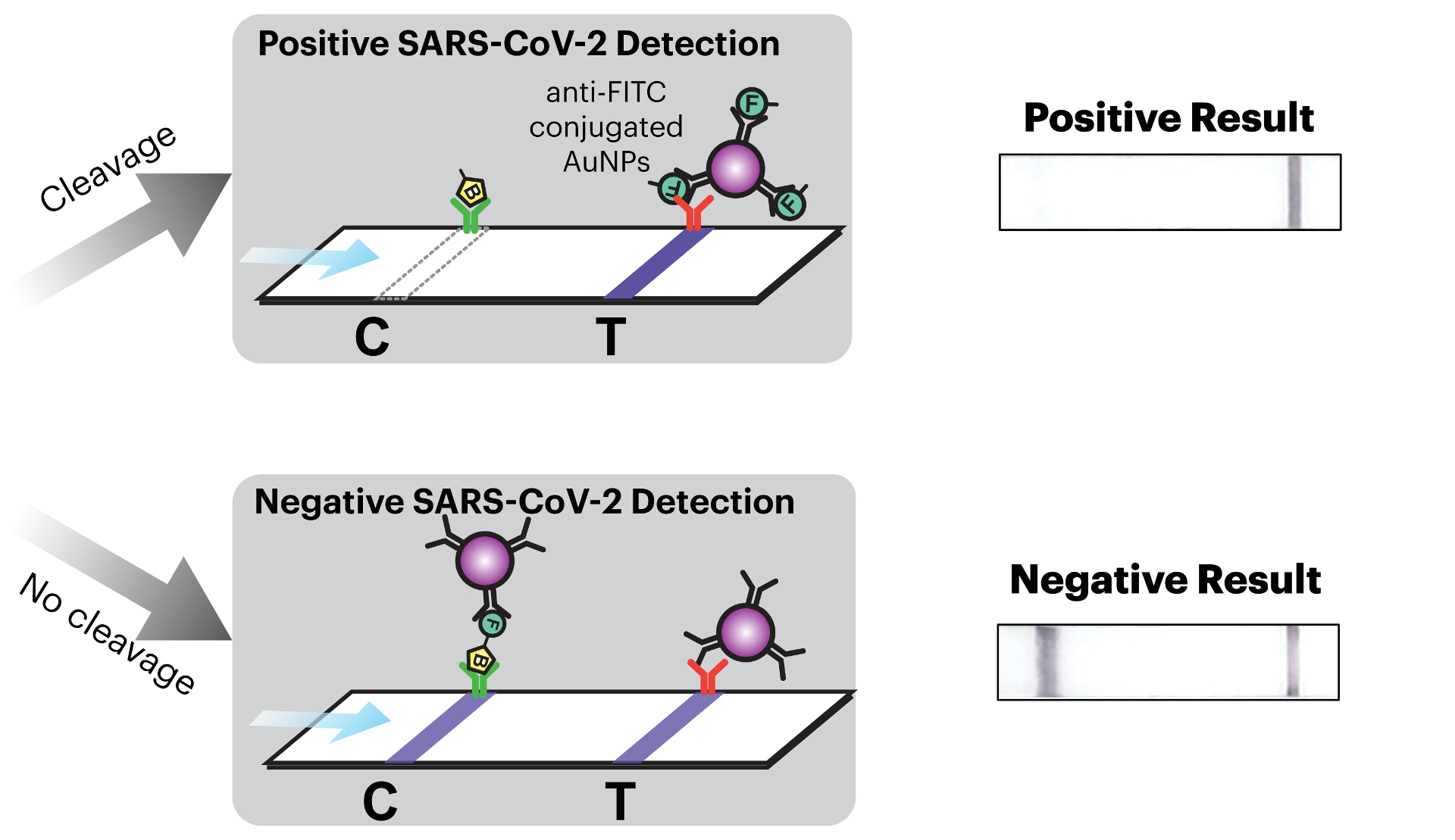

For example, if I’m designing a diagnostic device, I will listen to the scientists about how the fundamental biology works in their system and use my experience in sensor development, microsystems, and developing point-of-care devices to speak to more practically minded engineers about how to build the device, finding a common language between the two. Then, we need to communicate why this device is useful to a business audience in order to successfully commercialize it.

What brought you to the Wyss?

I wanted to be in a place that was busy doing what I had been doing for a while in Europe, which is translational science. The first place on my wish list was the Wyss Institute. I loved the work going on here; the organs-on-chips and the translational nature of the place. It’s quite unique in its structure. So, I got in touch with people working here, especially in Donald Ingber’s lab, and I was lucky that there was a position open when I applied.

Members of Don Ingber’s lab, including Adama, at the Wyss Retreat in 2022. Credit: Wyss Institute at Harvard University

How has your previous work experience shaped your approach to your work today?

Starting with my master’s and Ph.D., much of my work has focused on technology transfer. It’s shaped my approach to work because it has taught me to talk to different people, bring various viewpoints and skills together, really listen to where the problems are, and find solutions. I think sometimes, especially earlier in your career, it’s easy to think that your idea is brilliant, but at the end of the day, it might be a great technology that’s hard to translate into a product. I’ve learned that you need to take your ego out of it, listen, and find the best way forward, even if it isn’t your way. Having a critical mass of new knowledge around you means you’ll always be at the forefront; you just have to be open to trying new things and making the sum of the parts better than the individual pieces.

What is your biggest piece of advice for an academic scientist looking to translate their technology?

“Maintain a level of curiosity and wonder. Be prepared to keep on improving and learning.”

– Adama Sesay

Maintain a level of curiosity and wonder. Be prepared to keep on improving and learning. Don’t be discouraged if you get knocked back, because even if your first approach doesn’t work, it’s because you go through that and you’re willing to get back up again that you will succeed.

What inspired you to get into this field?

If you had asked me what I wanted to be when I was a kid, I would always say a doctor, an architect, or a firefighter. A doctor because I really liked science and I didn’t know there was anything else out there other than that. My parents were in the medical field, so I thought that was it. An architect because I liked art, and I love buildings. I thought architecture was the practical way to apply that. I was unaware there was a profession called an engineer. And a firefighter because I enjoy being active and I thought they were so heroic. I just admired them.

I realized very quickly that none of those things were exactly for me, but I followed the passions that led me to those ideas – science, design, and saving lives – and by doing what I love I found my way to a career in translational research focused on sensors and microsystems. If you really enjoy what you do, it doesn’t feel like a job.

What continues to motivate you?

Making a difference and working with a great team in an amazing work environment. I think that knowing that the people I’m working alongside are truly having an impact, even if they’re not on my project directly, is very inspiring. It makes me feel that I’m a part of something that can cause positive change in my lifetime.

“I think that knowing that the people I’m working alongside are truly having an impact, even if they’re not on my project directly, is very inspiring. It makes me feel that I’m a part of something that can cause positive change in my lifetime.”

– Adama Sesay

When not at the Wyss, how do you like to spend your time?

I like roller skating. I started playing my clarinet again, which I used to do when I was a teenager, and that’s given me a lot of joy. I also like watching films. My favorite recent films have been Everything, Everywhere, All at Once and The Woman King. Everything, Everywhere, All at Once manages to be light while also touching some quite thought-provoking concepts. I love the types of films that you can spend time talking about. The Woman King, while it has faced some criticism for being inaccurate, opens a dialogue about African history on a world stage between individuals whom audiences in the west have never known or even wondered about it. Although some of these discussions might be uncomfortable, at least people are beginning to have them. Again, I like a film that starts a conversation.

What’s something unique about you that someone wouldn’t know from your resume?

My mother suffered from Alzheimer’s disease, and it finally took her this past Christmas. In her memory, my sister and I are working towards building a smart city in her village in Sierra Leone. To do this, we’re raising awareness and funding to build an agricultural school for women and empower them to harvest crops based on new technology that’s sustainable and appropriate for the land, given that it’s a wildlife sanctuary area, and create businesses from farming. Hopefully, by next year we can start working on the curriculum for the school. We’re putting a lot of work into this, but we think it’s a great way to honor our mother’s legacy and enable women to get out of poverty and become future entrepreneurs.

What does it feel like to be working towards translating cutting-edge technology that has the potential to have a real and significant impact on people’s lives and society?

It feels great to be part of such a dynamic environment. I think as an engineer and a technology transfer specialist, it’s the best of all worlds. I’m lucky enough to have worked at some exceptional institutes in some amazing countries, but the Wyss is quite special in that we have a critical mass of world-class, high-impact projects ripe for translation. I’m in my fifth year now and it’s been a great ride so far. I’m looking forward to what comes next.