Year-to-Date Numbers Show Decline in Robotics (18%), Machine Vision (8%), and Motion Control (6%) Orders Compared to 2019

The human touch – Robots for completing tasks that require human senses

Amateur drone videos could aid in natural disaster damage assessment

Simplifying Motion Control through Integration of All System Components

AI and Decision Science – A forced marriage that is largely ignored

You might not be aware or do this unconsciously but, if you work with AI you also work in the decision science space.

Imagine this: You have made an AI model that can take in support tickets and classify them into different subjects and sentiments. With that you can prioritize support tickets by how critical they are and have them directed to the appropriate support team. Sounds great right? But is it really that simple? No. With the AI model in place we are really only halfway to the finish line. If you decided to make an AI like the one I just described you must have had the goal of optimizing the support ticket workflow. Either for happier customers or to lower costs or maybe some other business objective. Either way, the way we choose to act on the data we get as a result of the AI is equally important to the actual AI, if not more. When we take a stand on how to act on the data we get we actually make a decision model. The science that goes into these models are not as simple as it might sound. Look at this example:

The support ticket AI suggests that with 60% likelihood a new ticket is about termination, 30% about a new feature and scores medium critical on the sentiment analysis. Now it doesn’t seem so easy anymore does it? How do we handle this information? Who should get this ticket? And isn’t a termination critical no matter the sentiment score?

I’m in no way a decision scientist and cannot teach anyone much here. But what I can tell you for certain is that the decision models on top of AI are way too often left to be a secondary priority with no conscience or strategic approach. And even worse - The decision model is only discussed after we are finished with the AI models. I would argue that it is in the making of the decision model that we actually get to understand what data we really need, so making the AI first rarely makes sense since we don’t know what we actually need.

There’s also a lot of traps to be aware of in decision making such as survival bias(Thinking you made the right decision because you got the right result) and many of us think we are better decision makers than we really are.

If you want to learn more about decision science my best advice is to follow the Chief Decision Scientist at Google Cassie Kozyrkov. She really succeeds at taking decision science to an understandable level.

So to sum up. If we want to have better results with our AI solutions we should pay more attention to decision making and in many cases start with that before we go modelling.

Cutting surgical robots down to size

By Lindsay Brownell

Minimally invasive laparoscopic surgery, in which a surgeon uses tools and a tiny camera inserted into small incisions to perform operations, has made surgical procedures safer for both patients and doctors over the last half-century. Recently, surgical robots have started to appear in operating rooms to further assist surgeons by allowing them to manipulate multiple tools at once with greater precision, flexibility, and control than is possible with traditional techniques. However, these robotic systems are extremely large, often taking up an entire room, and their tools can be much larger than the delicate tissues and structures on which they operate.

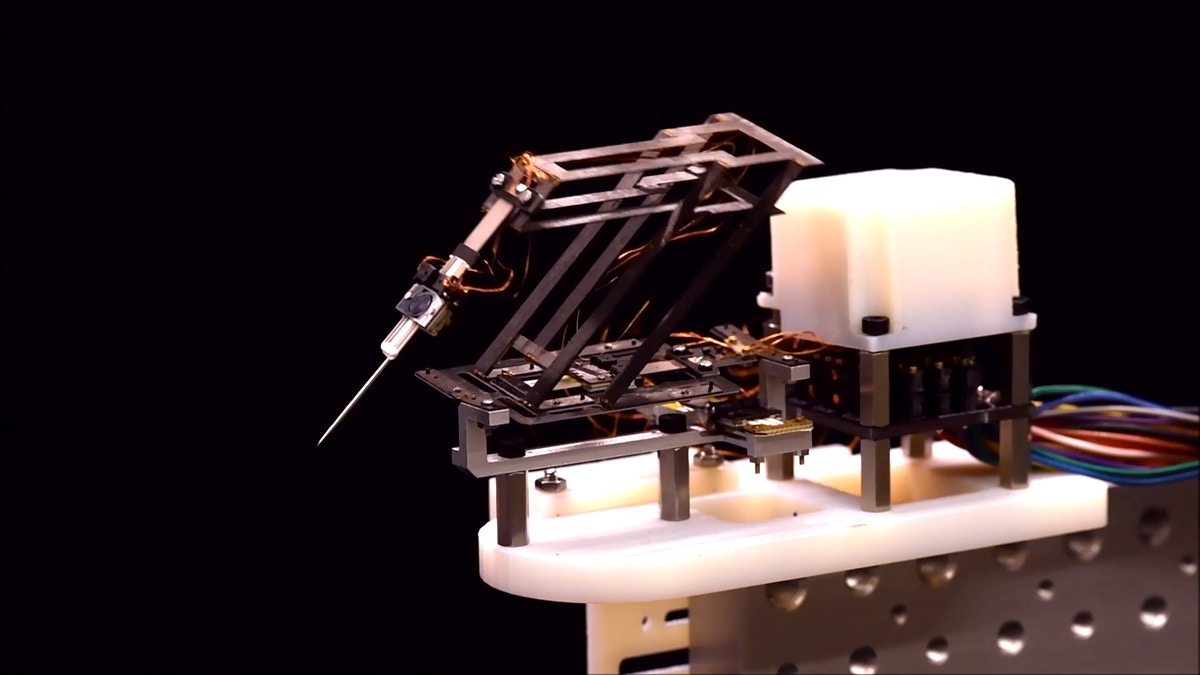

A collaboration between Wyss Associate Faculty member Robert Wood, Ph.D. and Robotics Engineer Hiroyuki Suzuki of Sony Corporation has brought surgical robotics down to the microscale by creating a new, origami-inspired miniature remote center of motion manipulator (the “mini-RCM”). The robot is the size of a tennis ball, weighs about as much as a penny, and successfully performed a difficult mock surgical task, as described in a recent issue of Nature Machine Intelligence.

“The Wood lab’s unique technical capabilities for making micro-robots have led to a number of impressive inventions over the last few years, and I was convinced that it also had the potential to make a breakthrough in the field of medical manipulators as well,” said Suzuki, who began working with Wood on the mini-RCM in 2018 as part of a Harvard-Sony collaboration. “This project has been a great success.”

A mini robot for micro tasks

To create their miniature surgical robot, Suzuki and Wood turned to the Pop-Up MEMS manufacturing technique developed in Wood’s lab, in which materials are deposited on top of each other in layers that are bonded together, then laser-cut in a specific pattern that allows the desired three-dimensional shape to “pop up,” as in a children’s pop-up picture book. This technique greatly simplifies the mass-production of small, complex structures that would otherwise have to be painstakingly constructed by hand.

The team created a parallelogram shape to serve as the main structure of the robot, then fabricated three linear actuators (mini-LAs) to control the robot’s movement: one parallel to the bottom of the parallelogram that raises and lowers it, one perpendicular to the parallelogram that rotates it, and one at the tip of the parallelogram that extends and retracts the tool in use. The result was a robot that is much smaller and lighter than other microsurgical devices previously developed in academia.

The mini-LAs are themselves marvels in miniature, built around a piezoelectric ceramic material that changes shape when an electrical field is applied. The shape change pushes the mini-LA’s “runner unit” along its “rail unit” like a train on train tracks, and that linear motion is harnessed to move the robot. Because piezoelectric materials inherently deform as they change shape, the team also integrated LED-based optical sensors into the mini-LA to detect and correct any deviations from the desired movement, such as those caused by hand tremors.

Steadier than a surgeon’s hands

To mimic the conditions of a teleoperated surgery, the team connected the mini-RCM to a Phantom Omni device, which manipulated the mini-RCM in response to the movements of a user’s hand controlling a pen-like tool. Their first test evaluated a human’s ability to trace a tiny square smaller than the tip of a ballpoint pen, looking through a microscope and either tracing it by hand, or tracing it using the mini-RCM. The mini-RCM tests dramatically improved user accuracy, reducing error by 68% compared to manual operation – an especially important quality given the precision required to repair small and delicate structures in the human body.

After the mini-RCM’s success on the tracing test, the researchers then created a mock version of a surgical procedure called retinal vein cannulation, in which a surgeon must carefully insert a needle through the eye to inject therapeutics into the tiny veins at the back of the eyeball. They fabricated a silicone tube the same size as the retinal vein (about twice the thickness of a human hair), and successfully punctured it with a needle attached to the end of the mini-RCM without causing local damage or disruption.

In addition to its efficacy in performing delicate surgical maneuvers, the mini-RCM’s small size provides another important benefit: it is easy to set up and install and, in the case of a complication or electrical outage, the robot can be easily removed from a patient’s body by hand.

“The Pop-Up MEMS method is proving to be a valuable approach in a number of areas that require small yet sophisticated machines, and it was very satisfying to know that it has the potential to improve the safety and efficiency of surgeries to make them even less invasive for patients,” said Wood, who is also the Charles River Professor of Engineering and Applied Sciences at Harvard’s John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS).

The researchers aim to increase the force of the robot’s actuators to cover the maximum forces experienced during an operation, and improve its positioning precision. They are also investigating using a laser with a shorter pulse during the machining process, to improve the mini-LAs’ sensing resolution.

“This unique collaboration between the Wood lab and Sony illustrates the benefits that can arise from combining the real-world focus of industry with the innovative spirit of academia, and we look forward to seeing the impact this work will have on surgical robotics in the near future,” said Wyss Institute Founding Director Don Ingber, M.D., Ph.D., who is also the the Judah Folkman Professor of Vascular Biology at Harvard Medical School and Boston Children’s Hospital, and Professor of Bioengineering at SEAS.

Microscopic robots ‘walk’ thanks to laser tech

A model for autonomous navigation and obstacle avoidance in UAVs

Putting Food Safety First With Robots – Could Robots Lead the Fight Against Contamination in Food Production Lines?

5 Ways COVID-19 Could Benefit the Robotics Market

Robotic arms extend the reach of UV disinfection

#317: Environmental Monitoring with the SlothBot, with Gennaro Notomista

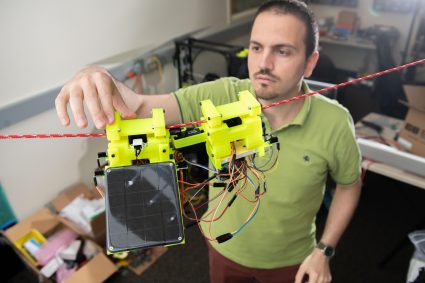

In this episode, Lauren Klein interviews Gennaro Notimista, a robotics PhD student in the Georgia Robotics and InTelligent Systems Laboratory at Georgia Tech. Gennaro discusses the SlothBot, a solar-powered robot that slowly traverses wires, like its animal namesake, to monitor the environment.

Gennaro Notomista

Gennaro Notomista is a robotics PhD student in the Georgia Robotics and InTelligent Systems Laboratory at Georgia Tech. Gennaro studies control frameworks, with the goal of making robots robust against a changing environment so they can handle long-duration deployments. Toward this goal, he explores constraints-driven control and approaches to coverage control, or enabling robots to traverse closed environments. In addition to the SlothBot, Gennaro has applied his research to areas such as autonomous driving and swarm robotics.

Links