Finding inspiration in starfish larva

The new microbot inspired by starfish larva stirs up plastic beads. (Image: Cornel Dillinger/ETH Zurich)

By Rahel Künzler

Among scientists, there is great interest in tiny machines that are set to revolutionise medicine. These microrobots, often only a fraction of the diameter of a hair, are made to swim through the body to deliver medication to specific areas and perform the smallest surgical procedures.

The designs of these robots are often inspired by natural microorganisms such as bacteria or algae. Now, for the first time, a research group at ETH Zurich has developed a microrobot design inspired by starfish larva, which use ciliary bands on their surface to swim and feed. The ultrasound-activated synthetic system mimics the natural arrangements of starfish ciliary bands and leverages nonlinear acoustics to replicate the larva’s motion and manipulation techniques.

Hairs to push liquid away or suck it in

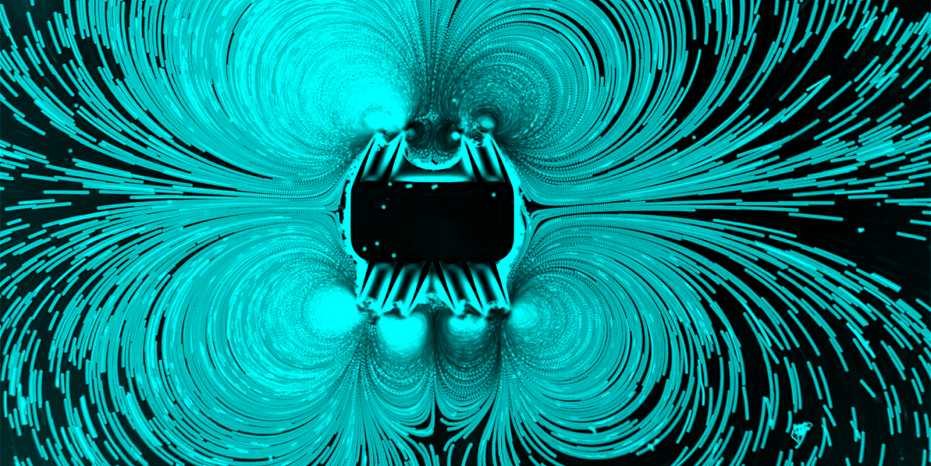

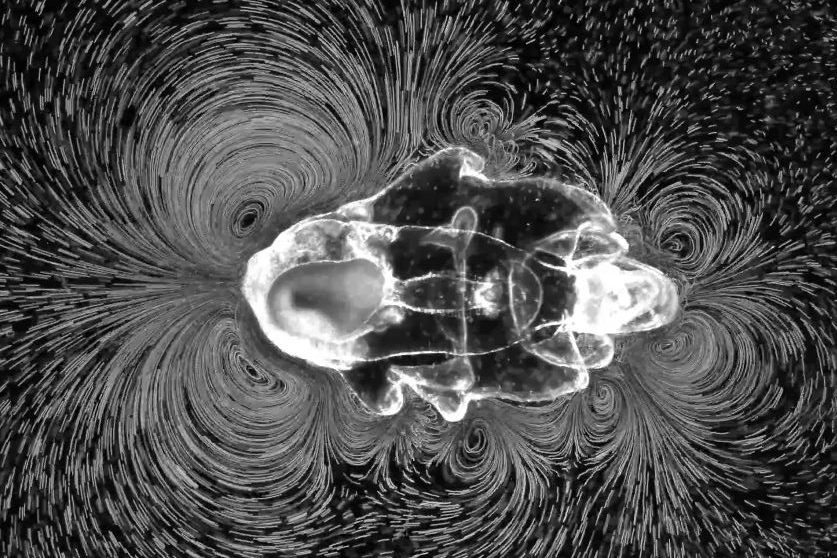

Depending on whether it is swimming or feeding, the starfish larva generates different patterns of vortices. (Image: Prakash Lab, Stanford University)

At first glance, the microrobots bear only scant similarity to starfish larva. In its larval stage, a starfish has a lobed body that measures just a few millimetres across. Meanwhile, the microrobot is a rectangle and ten times smaller, only a quarter of a millimetre across. But the two do share one important feature: a series of fine, movable hairs on the surface, called cilia.

A starfish larva is blanketed with hundreds of thousands of these hairs. Arranged in rows, they beat back and forth in a coordinated fashion, creating eddies in the surrounding water. The relative orientation of two rows determines the end result: Inclining two bands of beating cilia toward each other creates a vortex with a thrust effect, propelling the larva. On the other hand, inclining two bands away from each other creates a vortex that draws liquid in, trapping particles on which the larva feeds.

Artificial swimmers beat faster

These cilia were the key design element for the new microrobot developed by ETH researchers led by Daniel Ahmed, who is a Professor of Acoustic Robotics for life sciences and healthcare. “In the beginning,” Ahmed said, “we simply wanted to test whether we could create vortices similar to those of the starfish larva with rows of cilia inclined toward or away from each other.

To this end, the researchers used photolithography to construct a microrobot with appropriately inclined ciliary bands. They then applied ultrasound waves from an external source to make the cilia oscillate. The synthetic versions beat back and forth more than ten thousand times per second – about a thousand times faster than those of a starfish larva. And as with the larva, these beating cilia can be used to generate a vortex with a suction effect at the front and a vortex with a thrust effect at the rear, the combined effect “rocketing” the robot forward.

Besides swimming, the new microrobot can collect particles and steer them in a predetermined direction. (Video: Cornel Dillinger/ETH Zurich)

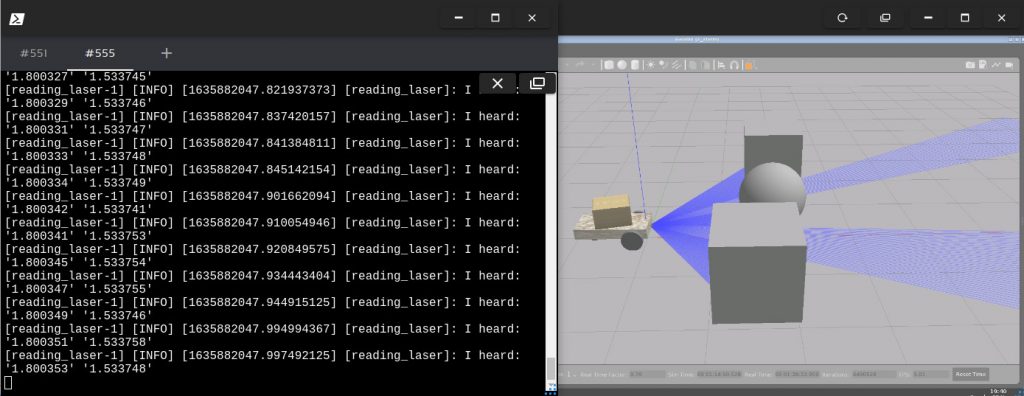

In their lab, the researchers showed that the microrobots can swim in a straight line through liquid such as water. Adding tiny plastic beads to the water made it possible to visualize the vortices created by the microrobot. The result is astonishing: both starfish larva and microrobots generate virtually identical flow patterns.

Next, the researchers arranged the ciliary bands so that a suction vortex was positioned next to a thrust vortex, imitating the feeding technique used by starfish larva. This arrangement enabled the robots to collect particles and send them out in a predetermined direction.

Ultrasound offers many advantages

Ahmed is convinced that this new type of microrobot will be ready for use in medicine in the foreseeable future. This is because a system that relies only on ultrasound offers decisive advantages: ultrasound waves are already widely used in imaging, penetrate deep inside the body, and pose no health risks.

“Our vision is to use ultrasound for propulsion, imaging and drug delivery.”

– Daniel Ahmed

The fact that this therapy requires only an ultrasound device makes it cheap, he adds, and hence suitable for use in both developed and developing countries.

Ahmed believes one initial field of application could be the treatment of gastric tumours. Uptake of conventional drugs by diffusion is inefficient, but having microrobots transport a drug specifically to the site of a stomach tumour and then deliver it there might make the drug’s uptake into tumour cells more efficient and reduce side effects.

Sharper images thanks to contrast agents

But before this vision can be realized, a major challenge remains to be overcome: imaging. Steering the tiny machines to the right place requires that a sharp image be generated in real time. The researchers have plans to make the microrobots more visible by incorporating contrast agents such as those already used in medical imaging with ultrasound.

In addition to medical applications, Ahmed anticipates this starfish-inspired design to have important implications for the manipulation of smallest liquid volumes in research and in industry. Bands of beating cilia could execute tasks such as mixing, pumping and particle trapping.

3D Vision System Nets the Right Tuna

Jason Richards: Robotic Food Delivery, Crowdfunding, and Working with Lawmakers | Sense Think Act Podcast #7

In this episode, Audrow Nash speaks to Jason Richards, CEO at DaxBot. DaxBot makes a charismatic robot for food delivery. Jason speaks on their delivery robot, their crowdfunding campaign, DaxBot’s revenue model, working with lawmakers to have robots on the sidewalks, and Jason teases their realtime operating system, DaxOS.

Episode Links

Podcast info

Machine Vision of Tomorrow: How 3D Scanning in Motion Revolutionizes Automation

Social robots deserve our appreciation, bioethicist says

Emerging Applications for Robotics in the Aerospace Industry: 5 Innovations

Exploring ROS2 with wheeled robot – #2 – How to subscribe to ROS2 laser scan topic

By Marco Arruda

This is the second chapter of the series “Exploring ROS2 with a wheeled robot”. In this episode, you’ll learn how to subscribe to a ROS2 topic using ROS2 C++.

You’ll learn:

- How to create a node with ROS2 and C++

- How to subscribe to a topic with ROS2 and C++

- How to launch a ROS2 node using a launch file

1 – Setup environment – Launch simulation

Before anything else, make sure you have the rosject from the previous post, you can copy it from here.

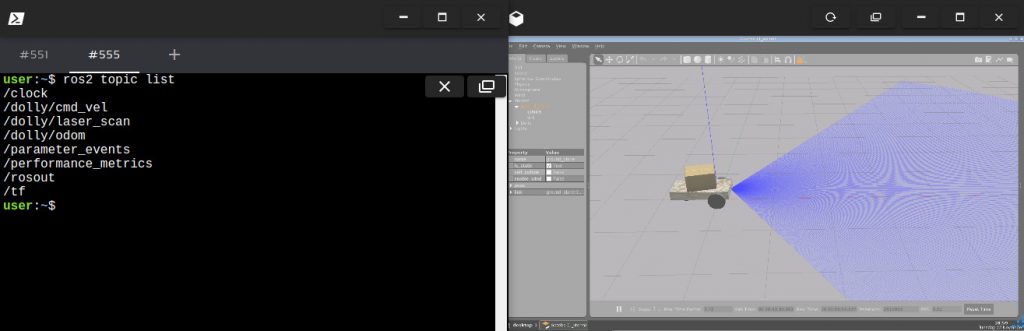

Launch the simulation in one webshell and in a different tab, checkout the topics we have available. You must get something similar to the image below:

2 – Create a ROS2 node

Our goal is to read the laser data, so create a new file called reading_laser.cpp:

touch ~/ros2_ws/src/my_package/reading_laser.cpp

And paste the content below:

#include "rclcpp/rclcpp.hpp"

#include "sensor_msgs/msg/laser_scan.hpp"

using std::placeholders::_1;

class ReadingLaser : public rclcpp::Node {

public:

ReadingLaser() : Node("reading_laser") {

auto default_qos = rclcpp::QoS(rclcpp::SystemDefaultsQoS());

subscription_ = this->create_subscription(

"laser_scan", default_qos,

std::bind(&ReadingLaser::topic_callback, this, _1));

}

private:

void topic_callback(const sensor_msgs::msg::LaserScan::SharedPtr _msg) {

RCLCPP_INFO(this->get_logger(), "I heard: '%f' '%f'", _msg->ranges[0],

_msg->ranges[100]);

}

rclcpp::Subscription::SharedPtr subscription_;

};

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

rclcpp::init(argc, argv);

auto node = std::make_shared();

RCLCPP_INFO(node->get_logger(), "Hello my friends");

rclcpp::spin(node);

rclcpp::shutdown();

return 0;

}

We are creating a new class ReadingLaser that represents the node (it inherits rclcpp::Node). The most important about that class are the subscriber attribute and the method callback. In the main function we are initializing the node and keep it alive (spin) while its ROS connection is valid.

The subscriber constructor expects to get a QoS, that stands for the middleware used for the quality of service. You can have more information about it in the reference attached, but in this post we are just using the default QoS provided. Keep in mind the following parameters:

- topic name

- callback method

The callback method needs to be binded, which means it will not be execute at the subscriber declaration, but when the callback is called. So we pass the reference of the method and setup the this reference for the current object to be used as callback, afterall the method itself is a generic implementation of a class.

3 – Compile and run

In order to compile the cpp file, we must add some instructions to the ~/ros2_ws/src/my_package/src/CMakeLists.txt:

- Look for find dependencies and include the sensor_msgs library

- Just before the install instruction add the executable and target its dependencies

- Append another install instruction for the new executable we’ve just created

# find dependencies

find_package(ament_cmake REQUIRED)

find_package(rclcpp REQUIRED)

find_package(sensor_msgs REQUIRED)

...

...

add_executable(reading_laser src/reading_laser.cpp)

ament_target_dependencies(reading_laser rclcpp std_msgs sensor_msgs)

...

...

install(TARGETS

reading_laser

DESTINATION lib/${PROJECT_NAME}/

)

Compile it:

colcon build --symlink-install --packages-select my_package

4 – Run the node and mapping the topic

In order to run the executable created, you can use:

ros2 run my_package reading_laser

Although the the laser values won’t show up. That’s because we have a “hard coded” topic name laser_scan. No problem at all, when we can map topics using launch files. Create a new launch file ~/ros2_ws/src/my_package/launch/reading_laser.py:

from launch import LaunchDescription

from launch_ros.actions import Node

def generate_launch_description():

reading_laser = Node(

package='my_package',

executable='reading_laser',

output='screen',

remappings=[

('laser_scan', '/dolly/laser_scan')

]

)

return LaunchDescription([

reading_laser

])

In this launch file there is an instance of a node getting the executable as argument and it is setup the remappings attribute in order to remap from laser_scan to /dolly/laser_scan.

Run the same node using the launch file this time:

ros2 launch my_package reading_laser.launch.py

Add some obstacles to the world and the result must be similar to: