The fast-changing customer demands in modern society seek flexibility, innovation and a rapid response from manufacturers and organisations that, in order to respond to market needs, are creating tools and processes in order to adopt an approach that welcomes change.

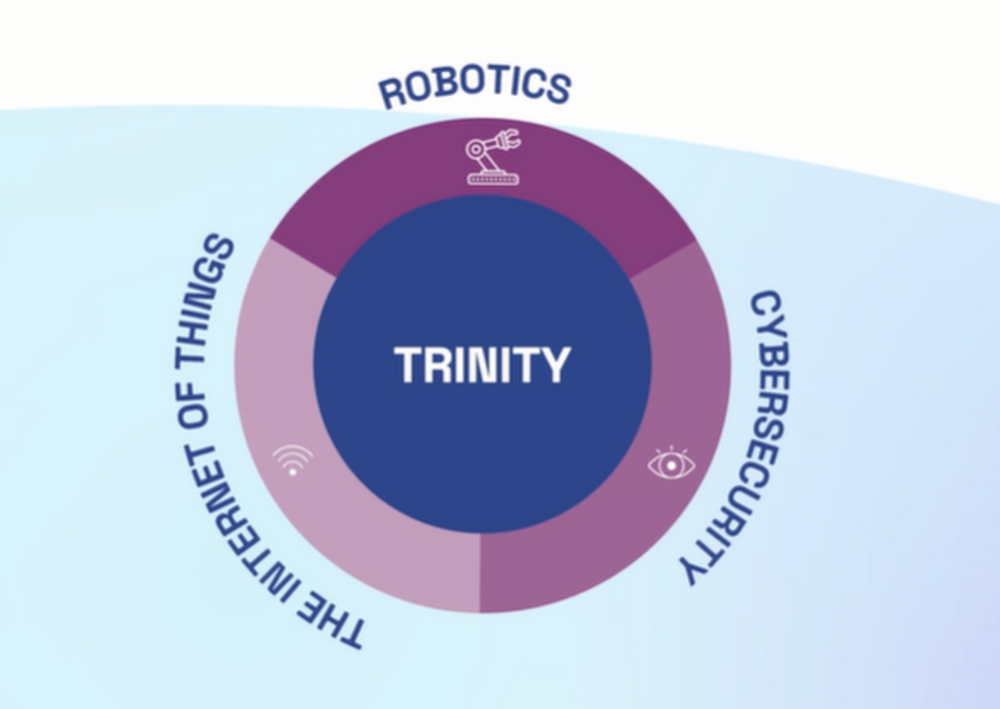

That approach is found to be Agile Manufacturing – and the Trinity project is the magnet that connects every segment of agile with everyone involved, creating a network that supports people, organisations, production and processes.

The main objective of TRINITY is to create a network of multidisciplinary and synergistic local digital innovation hubs (DIHs) composed of research centres, companies, and university groups that cover a wide range of topics that can contribute to agile production: advanced robotics as the driving force and digital tools, data privacy and cyber security technologies to support the introduction of advanced robotic systems in the production processes.

Trinity network

The Trinity project is funded by Horizon 2020 the European Union research and innovation programme.

Currently, Trinity brings together a network of 16 Digital Innovation Hubs (DIHs) and so far has 37 funded projects with 8.1 million euros in funding.

The network starts its operation by developing demonstrators in the areas of robotics it identified as the most promising to advance agile production, e.g. collaborative robotics including sensory systems to ensure safety, effective user interfaces based on augmented reality and speech, reconfigurable robot workcells and peripheral equipment (fixtures, jigs, grippers, …), programming by demonstration, IoT, secure wireless networks, etc.

These demonstrators will serve as a reference implementation for two rounds of open calls for application experiments, where companies with agile production needs and sound business plans will be supported by TRINITY DIHs to advance their manufacturing processes.

Trinity services

Besides technology-centred services, primary laboratories with advanced robot technologies and know-how to develop innovative application experiments, the TRINITY network of DIHS also offers training and consulting services, including support for business planning and access to financing.

All the data (including the current network list with partners, type of organisation and contact information) is available to everybody searching for the right type of help and guidance. The list also contains information regarding the Trinity funded projects and can be found on the website.

Robotics solution catalogue

Discover a wide range of Trinity solutions – from use cases like Predictable bin picking of shafts and axles, Robotic solution for accurate grinding of complex metal parts, End-to-end automatic handling of small packages and many more, to modules such are Additive TiG welding, Depth-sensor Safety Model for HRC, Environment Detection, Mobile Robot Motion Control and other, all that can be found in robotics solution catalogue on Trinity website.

Each of the solutions is followed up by a video that shows what made them successful, so whether it‘s about catalogue, modules, training materials, SME results, webinars or Trinity-related topics, the Trinity YouTube channel is where you will find it all.

Join us

Trinity wants to expand its current community made of more than 90 SMEs and around 20 organisations. If you are a Digital Innovation Hub, an innovative SME, a technical university, or a research centre focused on agile manufacturing, do not hesitate to contact us and exploit all the opportunities that Trinity offers.

You will be on board an ecosystem full of sectoral industry experts, facilities to put in practice your innovative ideas, and several partners with whom to develop new projects. Everything is on a user-centric platform and you will receive continuous support from the community!

Discuss with us

Be a part of the Trinity world by joining in on the discussions on agile production on social media or stay in touch with the latest news by signing in for the newsletter or simply by visiting the Trinity website.

Whatever your preferred type of communication is, all the contact information can be found here – so let‘s stay in touch!