Self-organization: What robotics can learn from amoebae

Ottonomy.IO Partners with Pittsburgh International Airport’s xBridge to Innovate Customer Experiences at the Airport

Benchmarking the next generation of never-ending learners

Benchmarking the next generation of never-ending learners

Benchmarking the next generation of never-ending learners

Benchmarking the next generation of never-ending learners

Benchmarking the next generation of never-ending learners

Benchmarking the next generation of never-ending learners

Benchmarking the next generation of never-ending learners

Benchmarking the next generation of never-ending learners

Multiple swimming robots able to create a vortex for transportation of microplastics

General Purpose Programming Languages Are the Future for the Industrial Automation Industry and Are Overtaking Traditional PLC IEC 61131-3

TRINITY, the European network for Agile Manufacturing

The fast-changing customer demands in modern society seek flexibility, innovation and a rapid response from manufacturers and organisations that, in order to respond to market needs, are creating tools and processes in order to adopt an approach that welcomes change.

That approach is found to be Agile Manufacturing – and the Trinity project is the magnet that connects every segment of agile with everyone involved, creating a network that supports people, organisations, production and processes.

The main objective of TRINITY is to create a network of multidisciplinary and synergistic local digital innovation hubs (DIHs) composed of research centres, companies, and university groups that cover a wide range of topics that can contribute to agile production: advanced robotics as the driving force and digital tools, data privacy and cyber security technologies to support the introduction of advanced robotic systems in the production processes.

Trinity network

The Trinity project is funded by Horizon 2020 the European Union research and innovation programme.

Currently, Trinity brings together a network of 16 Digital Innovation Hubs (DIHs) and so far has 37 funded projects with 8.1 million euros in funding.

The network starts its operation by developing demonstrators in the areas of robotics it identified as the most promising to advance agile production, e.g. collaborative robotics including sensory systems to ensure safety, effective user interfaces based on augmented reality and speech, reconfigurable robot workcells and peripheral equipment (fixtures, jigs, grippers, …), programming by demonstration, IoT, secure wireless networks, etc.

These demonstrators will serve as a reference implementation for two rounds of open calls for application experiments, where companies with agile production needs and sound business plans will be supported by TRINITY DIHs to advance their manufacturing processes.

Trinity services

Besides technology-centred services, primary laboratories with advanced robot technologies and know-how to develop innovative application experiments, the TRINITY network of DIHS also offers training and consulting services, including support for business planning and access to financing.

All the data (including the current network list with partners, type of organisation and contact information) is available to everybody searching for the right type of help and guidance. The list also contains information regarding the Trinity funded projects and can be found on the website.

Robotics solution catalogue

Discover a wide range of Trinity solutions – from use cases like Predictable bin picking of shafts and axles, Robotic solution for accurate grinding of complex metal parts, End-to-end automatic handling of small packages and many more, to modules such are Additive TiG welding, Depth-sensor Safety Model for HRC, Environment Detection, Mobile Robot Motion Control and other, all that can be found in robotics solution catalogue on Trinity website.

Each of the solutions is followed up by a video that shows what made them successful, so whether it‘s about catalogue, modules, training materials, SME results, webinars or Trinity-related topics, the Trinity YouTube channel is where you will find it all.

Join us

Trinity wants to expand its current community made of more than 90 SMEs and around 20 organisations. If you are a Digital Innovation Hub, an innovative SME, a technical university, or a research centre focused on agile manufacturing, do not hesitate to contact us and exploit all the opportunities that Trinity offers.

You will be on board an ecosystem full of sectoral industry experts, facilities to put in practice your innovative ideas, and several partners with whom to develop new projects. Everything is on a user-centric platform and you will receive continuous support from the community!

Discuss with us

Be a part of the Trinity world by joining in on the discussions on agile production on social media or stay in touch with the latest news by signing in for the newsletter or simply by visiting the Trinity website.

Whatever your preferred type of communication is, all the contact information can be found here – so let‘s stay in touch!

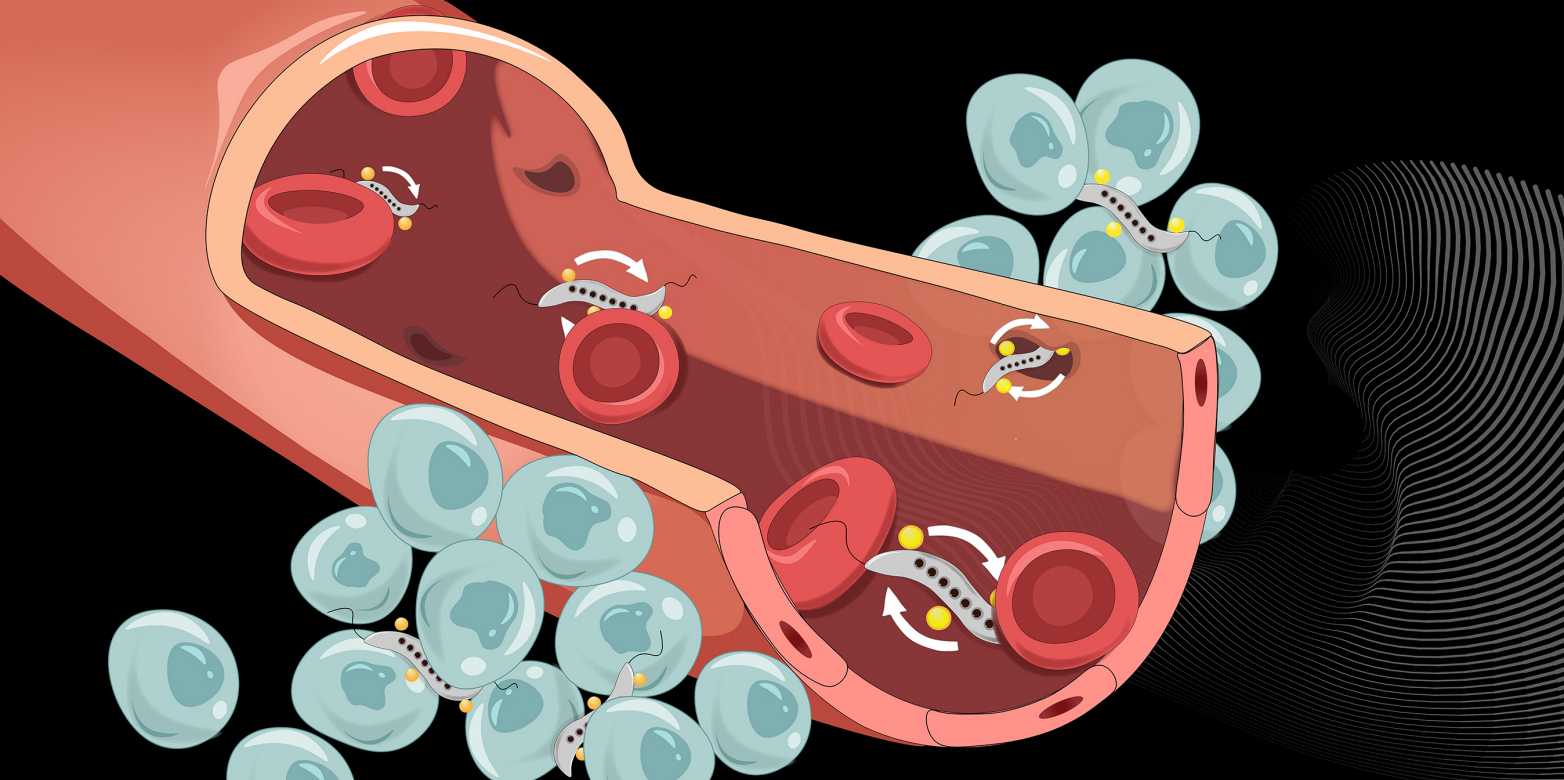

Fighting tumours with magnetic bacteria

Magnetic bacteria (grey) can squeeze through narrow intercellular spaces to cross the blood vessel wall and infiltrate tumours. (Visualisations: Yimo Yan / ETH Zurich)

By Fabio Bergamin

Scientists around the world are researching how anti-cancer drugs can most efficiently reach the tumours they target. One possibility is to use modified bacteria as “ferries” to carry the drugs through the bloodstream to the tumours. Researchers at ETH Zurich have now succeeded in controlling certain bacteria so that they can effectively cross the blood vessel wall and infiltrate tumour tissue.

Led by Simone Schürle, Professor of Responsive Biomedical Systems, the ETH Zurich researchers chose to work with bacteria that are naturally magnetic due to iron oxide particles they contain. These bacteria of the genus Magnetospirillum respond to magnetic fields and can be controlled by magnets from outside the body; for more on this, see an earlier article in ETH News.

Exploiting temporary gaps

In cell cultures and in mice, Schürle and her team have now shown that a rotating magnetic field applied at the tumour improves the bacteria’s ability to cross the vascular wall near the cancerous growth. At the vascular wall, the rotating magnetic field propels the bacteria forward in a circular motion.

To better understand the mechanism to cross the vessel wall works, a detailed look is necessary: The blood vessel wall consists of a layer of cells and serves as a barrier between the bloodstream and the tumour tissue, which is permeated by many small blood vessels. Narrow spaces between these cells allow certain molecules from the to pass through the vessel wall. How large these intercellular spaces are is regulated by the cells of the vessel wall, and they can be temporarily wide enough to allow even bacteria to pass through the vessel wall.

Strong propulsion and high probability

With the help of experiments and computer simulations, the ETH Zurich researchers were able to show that propelling the bacteria using a rotating magnetic field is effective for three reasons. First, propulsion via a rotating magnetic field is ten times more powerful than propulsion via a static magnetic field. The latter merely sets the direction and the bacteria have to move under their own power.

The second and most critical reason is that bacteria driven by the rotating magnetic field are constantly in motion, travelling along the vascular wall. This makes them more likely to encounter the gaps that briefly open between vessel wall cells compared to other propulsion types, in which the bacteria’s motion is less explorative. And third, unlike other methods, the bacteria do not need to be tracked via imaging. Once the magnetic field is positioned over the tumour, it does not need to be readjusted.

“Cargo” accumulates in tumour tissue

“We make use of the bacteria’s natural and autonomous locomotion as well,” Schürle explains. “Once the bacteria have passed through the blood vessel wall and are in the tumour, they can independently migrate deep into its interior.” For this reason, the scientists use the propulsion via the external magnetic field for just one hour – long enough for the bacteria to efficiently pass through the vascular wall and reach the tumour.

Such bacteria could carry anti-cancer drugs in the future. In their cell culture studies, the ETH Zurich researchers simulated this application by attaching liposomes (nanospheres of fat-like substances) to the bacteria. They tagged these liposomes with a fluorescent dye, which allowed them to demonstrate in the Petri dish that the bacteria had indeed delivered their “cargo” inside the cancerous tissue, where it accumulated. In a future medical application, the liposomes would be filled with a drug.

Bacterial cancer therapy

Using bacteria as ferries for drugs is one of two ways that bacteria can help in the fight against cancer. The other approach is over a hundred years old and currently experiencing a revival: using the natural propensity of certain species of bacteria to damage tumour cells. This may involve several mechanisms. In any case, it is known that the bacteria stimulate certain cells of the immune system, which then eliminate the tumour.

“We think that we can increase the efficacy of bacterial cancer therapy by using a engineering approach.”

– Simone Schürle

Multiple research projects are currently investigating the efficacy of E. coli bacteria against tumours. Today, it is possible to modify bacteria using synthetic biology to optimise their therapeutic effect, reduce side effects and make them safer.

Making non-magnetic bacteria magnetic

Yet to use the inherent properties of bacteria in cancer therapy, the question of how these bacteria can reach the tumour efficiently still remains. While it is possible to inject the bacteria directly into tumours near the surface of the body, this is not possible for tumours deep inside the body. That is where Professor Schürle’s microrobotic control comes in. “We believe we can use our engineering approach to increase the efficacy of bacterial cancer therapy,” she says.

E. coli used in the cancer studies is not magnetic and thus cannot be propelled and controlled by a magnetic field. In general, magnetic responsiveness is a very rare phenomenon among bacteria. Magnetospirillum is one of the few genera of bacteria that have this property.

Schürle therefore wants to make E. coli bacteria magnetic as well. This could one day make it possible to use a magnetic field to control clinically used therapeutic bacteria that have no natural magnetism.