Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems in Stuttgart have developed a soft robotic tool that promises to one day transform minimally invasive endovascular surgery. The two-part magnetic tool can help to visualise in real time the fine morphological details of partial vascular blockages such as stenoses, even in the narrowest and most curved vessels. It can also find its way through severe blockages such as chronic total occlusions. This tool could one day take the perception of endovascular medical devices a step further.

Intravascular imaging techniques and microcatheter procedures are becoming ever more advanced, revolutionizing the diagnosis and treatment of many diseases. However, current methods often fail to accurately detect the fine features of vascular disease, such as those seen from within occluded vessels, due to limitations such as uneven contrast agent diffusion and difficulty in safely accessing occluded vessels. Such limitations can delay rapid intervention and treatment of a patient.

Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems in Stuttgart have looked at this problem. They have leveraged the concepts of soft robotics and microfabrication to develop a miniature soft magnetic tool that looks like a very slim eel. This tool may one day take the perception capabilities of endovascular devices one step further. In a paper and in a video, the team shows how the tool, which is propelled forward by the blood flow, travels through the narrowest artificial vessels – whether there is a sharp bend, curve, or obstacle.

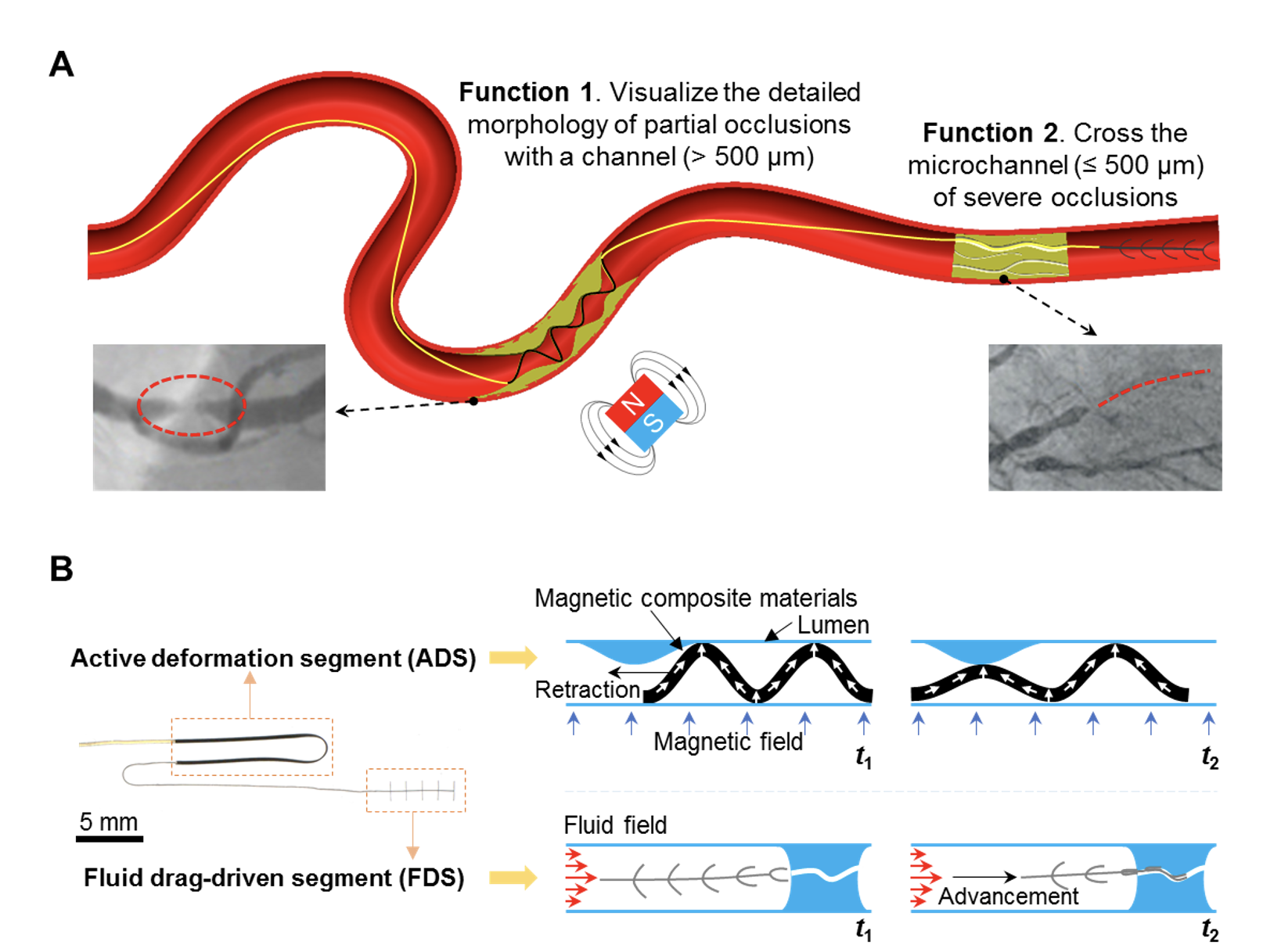

When the tool reaches an occlusion like a partially blocked artery, it performs a wave-like deformation given the external magnetic field (more on that below). Then, the deformed soft body will be gently in contact with the surrounding occluded structures. Lastly, the real-time shapes of the device when we retract it will ‘visualize’ the morphological details inside the vessel, which facilitates the drug release at occlusion, as well as the sizing and placement of medical devices like stents and balloons for following treatment.

When there is a severe occlusion with only tiny microchannels for the blood to flow through, the tool can utilize the force from the blood to easily slide through these narrow channels. Which way was chosen indicates to the surgeon which access route to take for the following medical operation.

“The methods of diagnosing and treating endovascular narrow diseases such as vascular stenosis or chronic total occlusion are still very limited. It is difficult to accurately detect and cross these areas in the very complex network of vessels inside the body”, says Yingbo Yan, who is a guest researcher in the Physical Intelligence Department at MPI-IS. He is the first author of the paper “Magnetically-assisted soft milli-tools for occluded lumen morphology detection”, which was published in Science Advances on August 18, 2023. “We hope that our new soft robotic tool can one day help accurately detect and navigate through the many complex and narrow vessels inside a body, and perform treatments more effectively, reducing potential risks.”

This tiny and soft tool has a 20 mm long magnetic Active Deformation Segment (ADS) and a 5mm long Fluid Drag-driven Segment (FDS). The magnetization profile of ADS is pre-programmed with a vibrating-sample magnetometer, providing a uniform magnetic field. Under an external magnetic field, this part can deform into a sinusoidal shape, easily adapting to the surrounding environment and deforming into various shapes. Thus, continuous monitoring of the shape changes of ADS while retracting it can provide detailed morphological information of the partial occlusions inside a vessel.

The FDS was fabricated using a soft polymer. Small beams on its side are bent by the fluidic drag from the incoming flow. In this way, the entire tool is carried towards the area with the highest flow velocity. Therefore, learning the location of the FDS while advancing it can point to the location and the route of the microchannel inside the severe occlusions.

“Detection of vascular diseases in the distal and hard-to-reach vascular regions such as the brain can be more challenging clinically, and our tool could work with Stentbot in the untethered mode”, says Tianlu Wang, a postdoc in the Physical Intelligence Department at MPI-IS and another first author of the work. “Stentbot is a wireless robot used for locomotion and medical functions in the distal vasculature we recently developed in our research group. We believe this new soft robotic tool can add new capabilities to wireless robots and contribute new solutions in these challenging regions.”

“Our tool shows potential to greatly improve minimally invasive medicine. This technology can reach and detect areas that were previously difficult to access. We expect that our robot can help make the diagnosis and treatment of, for instance, stenosis or a CTO more precise and timelier”, says Metin Sitti, Director of the Physical Intelligence Department at MPI-IS, Professor at Koç University and ETH Zurich.