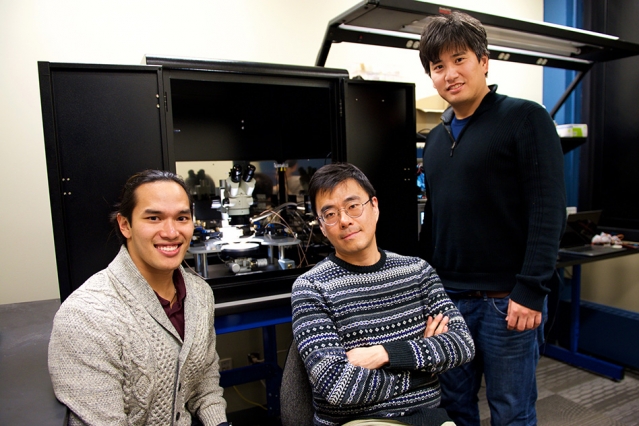

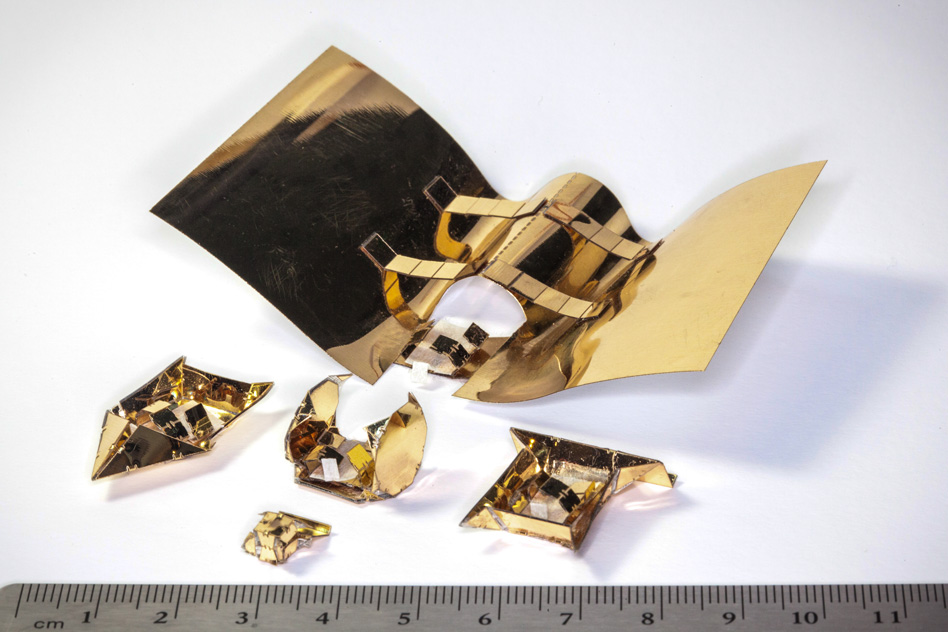

Photo: David Sella

By Eric Brown

If you were to ask someone to name a new technology that emerged from MIT in the 21st century, there’s a good chance they would name the robotic cheetah. Developed by the MIT Department of Mechanical Engineering’s Biomimetic Robotics Lab under the direction of Associate Professor Sangbae Kim, the quadruped MIT Cheetah has made headlines for its dynamic legged gait, speed, jumping ability, and biomimetic design.

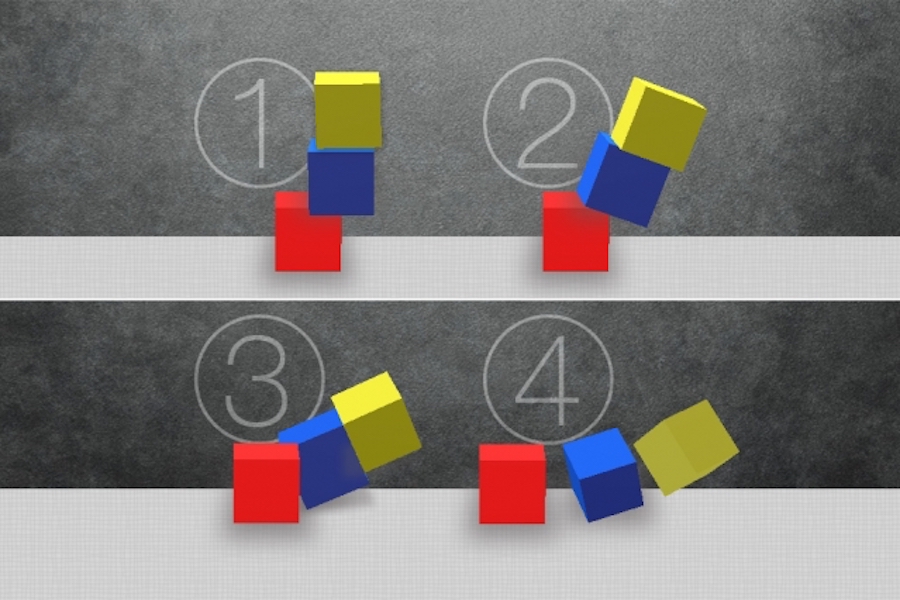

The dog-sized Cheetah II can run on four articulated legs at up to 6.4 meters per second, make mild running turns, and leap to a height of 60 centimeters. The robot can also autonomously determine how to avoid or jump over obstacles.

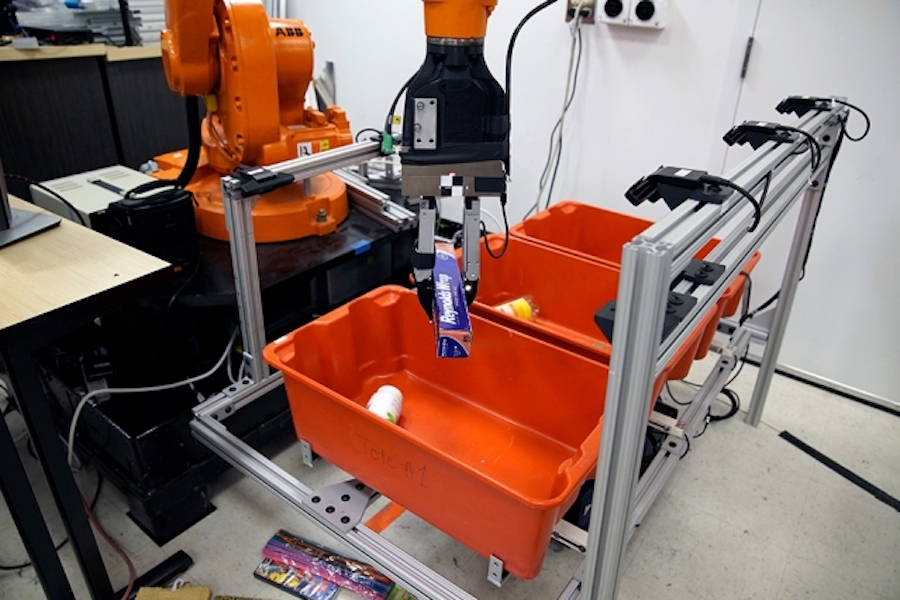

Kim is now developing a third-generation robot, the Cheetah III. Instead of improving the Cheetah’s speed and jumping capabilities, Kim is converting the Cheetah into a commercially viable robot with enhancements such as a greater payload capability, wider range of motion, and a dexterous gripping function. The Cheetah III will initially act as a spectral inspection robot in hazardous environments such as a compromised nuclear plant or chemical factory. It will then evolve to serve other emergency response needs.

“The Cheetah II was focused on high speed locomotion and agile jumping, but was not designed to perform other tasks,” says Kim. “With the Cheetah III, we put a lot of practical requirements on the design so it can be an all-around player. It can do high-speed motion and powerful actions, but it can also be very precise.”

The Biomimetic Robotics Lab is also finishing up a smaller, stripped down version of the Cheetah, called the Mini Cheetah, designed for robotics research and education. Other projects include a teleoperated humanoid robot called the Hermes that provides haptic feedback to human operators. There’s also an early stage investigation into applying Cheetah-like actuator technology to address mobility challenges among the disabled and elderly.

Conquering mobility on the land

“With the Cheetah project, I was initially motivated by copying land animals, but I also realized there was a gap in ground mobility,” says Kim. “We have conquered air and water transportation, but we haven’t conquered ground mobility because our technologies still rely on artificially paved roads or rails. None of our transportation technologies can reliably travel over natural ground or even man-made environments with stairs and curbs. Dynamic legged robots can help us conquer mobility on the ground.”

One challenge with legged systems is that they “need high torque actuators,” says Kim. “A human hip joint can generate more torque than a sports car, but achieving such condensed high torque actuation in robots is a big challenge.”

Robots tend to achieve high torque at the expense of speed and flexibility, says Kim. Factory robots use high torque actuators but they are rigid and cannot absorb energy upon the impact that results from climbing steps. Hydraulically powered, dynamic legged robots, such as the larger, higher-payload, quadruped Big Dog from Boston Dynamics, can achieve very high force and power, but at the expense of efficiency. “Efficiency is a serious issue with hydraulics, especially when you move fast,” he adds.

A chief goal of the Cheetah project has been to create actuators that can generate high torque in designs that imitate animal muscles while also achieving efficiency. To accomplish this, Kim opted for electric rather than hydraulic actuators. “Our high torque electric motors have exceeded the efficiency of animals with biological muscles, and are much more efficient, cheaper, and faster than hydraulic robots,” he says.

Cheetah III: More than a speedster

Unlike the earlier versions, the Cheetah III design was motivated more by potential applications than pure research. Kim and his team studied the requirements for an emergency response robot and worked backward.

“We believe the Cheetah III will be able to navigate in a power plant with radiation in two or three years,” says Kim. “In five to 10 years it should be able to do more physical work like disassembling a power plant by cutting pieces and bringing them out. In 15 to 20 years, it should be able to enter a building fire and possibly save a life.”

In situations such as the Fukushima nuclear disaster, robots or drones are the only safe choice for reconnaissance. Drones have some advantages over robots, but they cannot apply large forces necessary for tasks such as opening doors, and there are many disaster situations in which fallen debris prohibits drone flight.

By comparison, the Cheetah III can apply human-level forces to the environment for hours at a time. It can often climb or jump over debris, or even move it out of the way. Compared to a drone, it’s also easier for a robot to closely inspect instrumentation, flip switches, and push buttons, says Kim. “The Cheetah III can measure temperatures or chemical compounds, or close and open valves.”

Advantages over tracked robots include the ability to maneuver over debris and climb stairs. “Stairs are some of the biggest obstacles for robots,” says Kim. “We think legged robots are better in man-made environments, especially in disaster situations where there are even more obstacles.”

The Cheetah III was slowed down a bit compared to the Cheetah II, but also given greater strength and flexibility. “We increased the torque so it can open the heavy doors found in power plants,” says Kim. “We increased the range of motion to 12 degrees of freedom by using 12 electric motors that can articulate the body and the limbs.”

This is still far short of the flexibility of animals, which have over 600 muscles. Yet, the Cheetah III can compensate somewhat with other techniques. “We maximize each joint’s work space to achieve a reasonable amount of reachability,” says Kim.

The design can even use the legs for manipulation. “By utilizing the flexibility of the limbs, the Cheetah III can open the door with one leg,” says Kim. “It can stand on three legs and equip the fourth limb with a customized swappable hand to open the door or close a valve.”

The Cheetah III has an improved payload capability to carry heavier sensors and cameras, and possibly even to drop off supplies to disabled victims. However, it’s a long way from being able to rescue them. The Cheetah III is still limited to a 20-kilogram payload, and can travel untethered for four to five hours with a minimal payload.

“Eventually, we hope to develop a machine that can rescue a person,” says Kim. “We’re not sure if the robot would carry the victim or bring a carrying device,” he says. “Our current design can at least see if there are any victims or if there are any more potential dangerous events.”

Experimenting with human-robot interaction

The semiautonomous Cheetah III can make ambulatory and navigation decisions on its own. However, for disaster work, it will primarily operate by remote control.

“Fully autonomous inspection, especially in disaster response, would be very hard,” says Kim. Among other issues, autonomous decision making often takes time, and can involve trial and error, which could delay the response.

“People will control the Cheetah III at a high level, offering assistance, but not handling every detail,” says Kim. “People could tell it to go to a specific location at the map, find this place, and open that door. When it comes to hand action or manipulation, the human will take over more control and tell the robot what tool to use.”

Humans may also be able to assist with more instinctive controls. For example, if the Cheetah uses one of its legs as an arm and then applies force, it’s hard to maintain balance. Kim is now investigating whether human operators can use “balanced feedback” to keep the Cheetah from falling over while applying full force.

“Even standing on two or three legs, it would still be able to perform high force actions that require complex balancing,” says Kim. “The human operator can feel the balance, and help the robot shift its momentum to generate more force to open or hammer a door.”

The Biomimetic Robotics Lab is exploring balanced feedback with another robot project called Hermes (Highly Efficient Robotic Mechanisms and Electromechanical System). Like the Cheetah III, it’s a fully articulated, dynamic legged robot designed for disaster response. Yet, the Hermes is bipedal, and completely teleoperated by a human who wears a telepresence helmet and a full body suit. Like the Hermes, the suit is rigged with sensors and haptic feedback devices.

“The operator can sense the balance situation and react by using body weight or directly implementing more forces,” says Kim.

The latency required for such intimate real-time feedback is difficult to achieve with Wi-Fi, even when it’s not blocked by walls, distance, or wireless interference. “In most disaster situations, you would need some sort of wired communication,” says Kim. “Eventually, I believe we’ll use reinforced optical fibers.”

Improving mobility for the elderly

Looking beyond disaster response, Kim envisions an important role for agile, dynamic legged robots in health care: improving mobility for the fast-growing elderly population. Numerous robotics projects are targeting the elderly market with chatty social robots. Kim is imagining something more fundamental.

“We still don’t have a technology that can help impaired or elderly people seamlessly move from the bed to the wheelchair to the car and back again,” says Kim. “A lot of elderly people have problems getting out of bed and climbing stairs. Some elderly with knee joint problems, for example, are still pretty mobile on flat ground, but can’t climb down the stairs unassisted. That’s a very small fraction of the day when they need help. So we’re looking for something that’s lightweight and easy to use for short-time help.”

Kim is currently working on “creating a technology that could make the actuator safe,” he says. “The electric actuators we use in the Cheetah are already safer than other machines because they can easily absorb energy. Most robots are stiff, which would cause a lot of impact forces. Our machines give a little.”

By combining such safe actuator technology with some of the Hermes technology, Kim hopes to develop a robot that can help elderly people in the future. “Robots can not only address the expected labor shortages for elder care, but also the need to maintain privacy and dignity,” he says.