In recent years, the best-performing artificial-intelligence systems — in areas such as autonomous driving, speech recognition, computer vision, and automatic translation — have come courtesy of software systems known as neural networks.

But neural networks take up a lot of memory and consume a lot of power, so they usually run on servers in the cloud, which receive data from desktop or mobile devices and then send back their analyses.

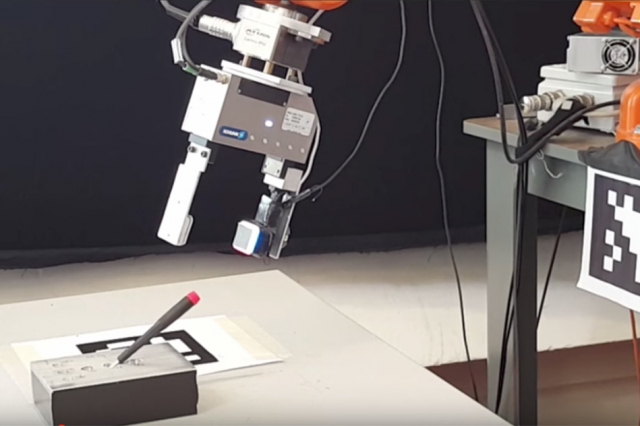

Last year, MIT associate professor of electrical engineering and computer science Vivienne Sze and colleagues unveiled a new, energy-efficient computer chip optimized for neural networks, which could enable powerful artificial-intelligence systems to run locally on mobile devices.

Now, Sze and her colleagues have approached the same problem from the opposite direction, with a battery of techniques for designing more energy-efficient neural networks. First, they developed an analytic method that can determine how much power a neural network will consume when run on a particular type of hardware. Then they used the method to evaluate new techniques for paring down neural networks so that they’ll run more efficiently on handheld devices.

The researchers describe the work in a paper they’re presenting next week at the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference. In the paper, they report that the methods offered as much as a 73 percent reduction in power consumption over the standard implementation of neural networks, and as much as a 43 percent reduction over the best previous method for paring the networks down.

Energy evaluator

Loosely based on the anatomy of the brain, neural networks consist of thousands or even millions of simple but densely interconnected information-processing nodes, usually organized into layers. Different types of networks vary according to their number of layers, the number of connections between the nodes, and the number of nodes in each layer.

The connections between nodes have “weights” associated with them, which determine how much a given node’s output will contribute to the next node’s computation. During training, in which the network is presented with examples of the computation it’s learning to perform, those weights are continually readjusted, until the output of the network’s last layer consistently corresponds with the result of the computation.

“The first thing we did was develop an energy-modeling tool that accounts for data movement, transactions, and data flow,” Sze says. “If you give it a network architecture and the value of its weights, it will tell you how much energy this neural network will take. One of the questions that people had is ‘Is it more energy efficient to have a shallow network and more weights or a deeper network with fewer weights?’ This tool gives us better intuition as to where the energy is going, so that an algorithm designer could have a better understanding and use this as feedback. The second thing we did is that, now that we know where the energy is actually going, we started to use this model to drive our design of energy-efficient neural networks.”

In the past, Sze explains, researchers attempting to reduce neural networks’ power consumption used a technique called “pruning.” Low-weight connections between nodes contribute very little to a neural network’s final output, so many of them can be safely eliminated, or pruned.

Principled pruning

With the aid of their energy model, Sze and her colleagues — first author Tien-Ju Yang and Yu-Hsin Chen, both graduate students in electrical engineering and computer science — varied this approach. Although cutting even a large number of low-weight connections can have little effect on a neural net’s output, cutting all of them probably would, so pruning techniques must have some mechanism for deciding when to stop.

The MIT researchers thus begin pruning those layers of the network that consume the most energy. That way, the cuts translate to the greatest possible energy savings. They call this method “energy-aware pruning.”

Weights in a neural network can be either positive or negative, so the researchers’ method also looks for cases in which connections with weights of opposite sign tend to cancel each other out. The inputs to a given node are the outputs of nodes in the layer below, multiplied by the weights of their connections. So the researchers’ method looks not only at the weights but also at the way the associated nodes handle training data. Only if groups of connections with positive and negative weights consistently offset each other can they be safely cut. This leads to more efficient networks with fewer connections than earlier pruning methods did.

“Recently, much activity in the deep-learning community has been directed toward development of efficient neural-network architectures for computationally constrained platforms,” says Hartwig Adam, the team lead for mobile vision at Google. “However, most of this research is focused on either reducing model size or computation, while for smartphones and many other devices energy consumption is of utmost importance because of battery usage and heat restrictions. This work is taking an innovative approach to CNN [convolutional neural net] architecture optimization that is directly guided by minimization of power consumption using a sophisticated new energy estimation tool, and it demonstrates large performance gains over computation-focused methods. I hope other researchers in the field will follow suit and adopt this general methodology to neural-network-model architecture design.”