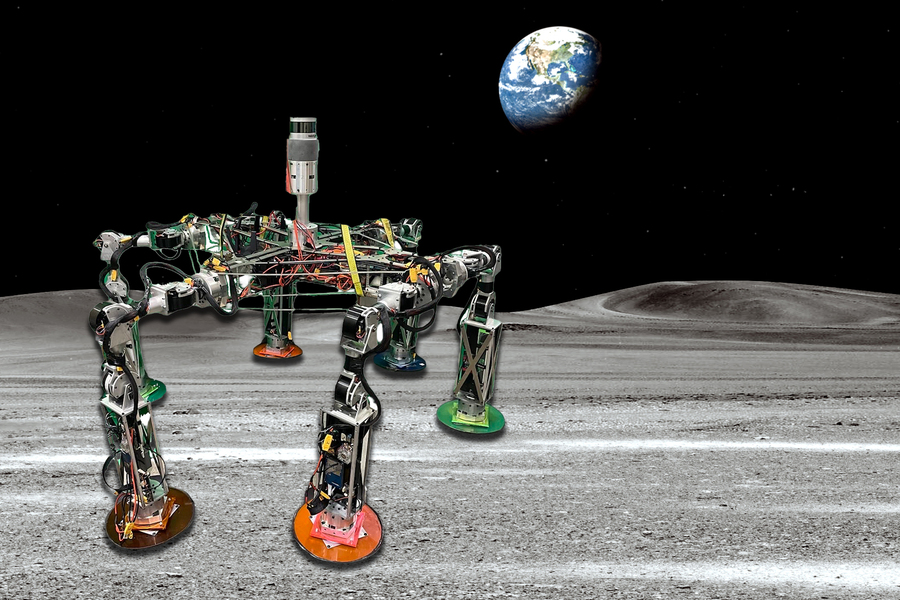

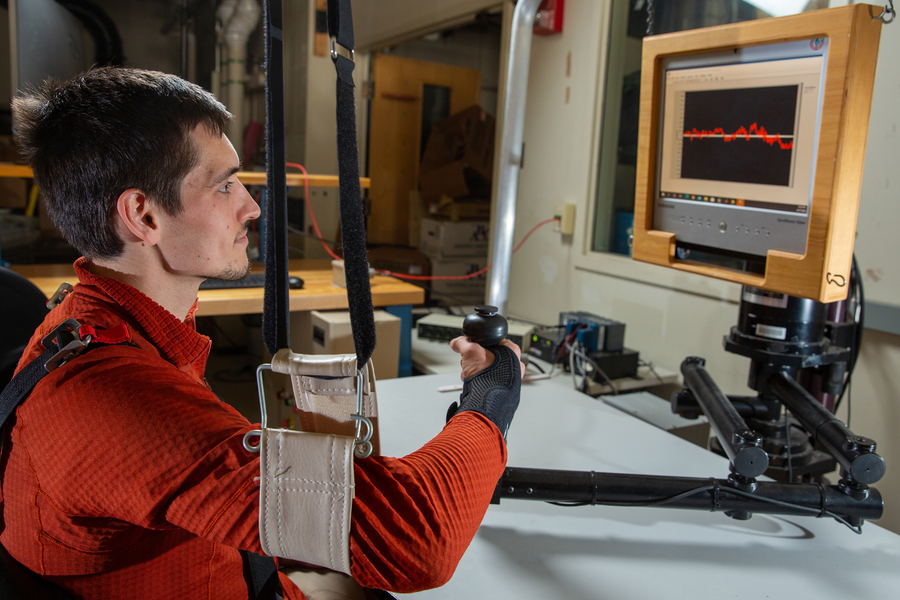

MIT researchers developed a machine-learning technique that can autonomously drive a car or fly a plane through a very difficult “stabilize-avoid” scenario, in which the vehicle must stabilize its trajectory to arrive at and stay within some goal region, while avoiding obstacles. Image: Courtesy of the researchers

By Adam Zewe | MIT News Office

In the film “Top Gun: Maverick,” Maverick, played by Tom Cruise, is charged with training young pilots to complete a seemingly impossible mission — to fly their jets deep into a rocky canyon, staying so low to the ground they cannot be detected by radar, then rapidly climb out of the canyon at an extreme angle, avoiding the rock walls. Spoiler alert: With Maverick’s help, these human pilots accomplish their mission.

A machine, on the other hand, would struggle to complete the same pulse-pounding task. To an autonomous aircraft, for instance, the most straightforward path toward the target is in conflict with what the machine needs to do to avoid colliding with the canyon walls or staying undetected. Many existing AI methods aren’t able to overcome this conflict, known as the stabilize-avoid problem, and would be unable to reach their goal safely.

MIT researchers have developed a new technique that can solve complex stabilize-avoid problems better than other methods. Their machine-learning approach matches or exceeds the safety of existing methods while providing a tenfold increase in stability, meaning the agent reaches and remains stable within its goal region.

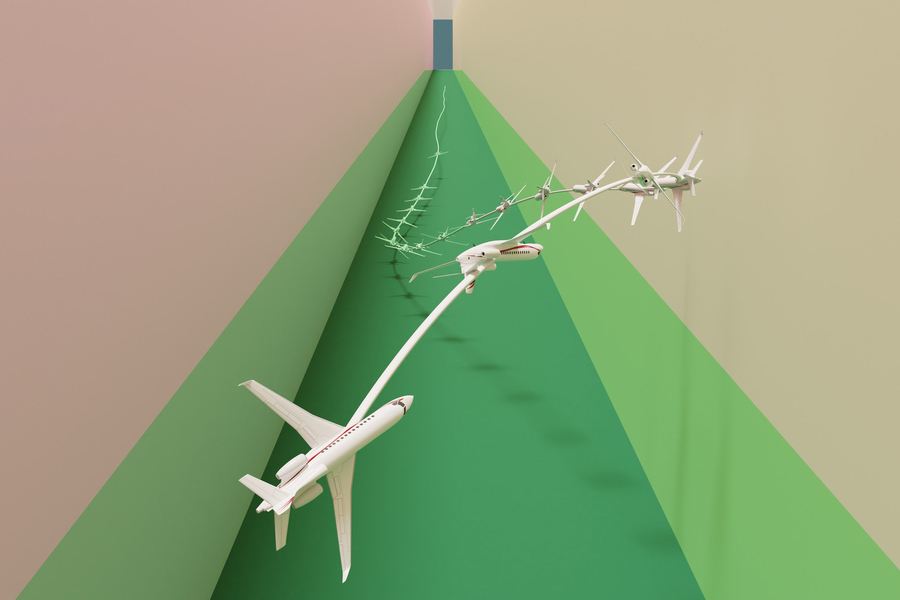

In an experiment that would make Maverick proud, their technique effectively piloted a simulated jet aircraft through a narrow corridor without crashing into the ground.

“This has been a longstanding, challenging problem. A lot of people have looked at it but didn’t know how to handle such high-dimensional and complex dynamics,” says Chuchu Fan, the Wilson Assistant Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics, a member of the Laboratory for Information and Decision Systems (LIDS), and senior author of a new paper on this technique.

Fan is joined by lead author Oswin So, a graduate student. The paper will be presented at the Robotics: Science and Systems conference.

The stabilize-avoid challenge

Many approaches tackle complex stabilize-avoid problems by simplifying the system so they can solve it with straightforward math, but the simplified results often don’t hold up to real-world dynamics.

More effective techniques use reinforcement learning, a machine-learning method where an agent learns by trial-and-error with a reward for behavior that gets it closer to a goal. But there are really two goals here — remain stable and avoid obstacles — and finding the right balance is tedious.

The MIT researchers broke the problem down into two steps. First, they reframe the stabilize-avoid problem as a constrained optimization problem. In this setup, solving the optimization enables the agent to reach and stabilize to its goal, meaning it stays within a certain region. By applying constraints, they ensure the agent avoids obstacles, So explains.

Then for the second step, they reformulate that constrained optimization problem into a mathematical representation known as the epigraph form and solve it using a deep reinforcement learning algorithm. The epigraph form lets them bypass the difficulties other methods face when using reinforcement learning.

“But deep reinforcement learning isn’t designed to solve the epigraph form of an optimization problem, so we couldn’t just plug it into our problem. We had to derive the mathematical expressions that work for our system. Once we had those new derivations, we combined them with some existing engineering tricks used by other methods,” So says.

No points for second place

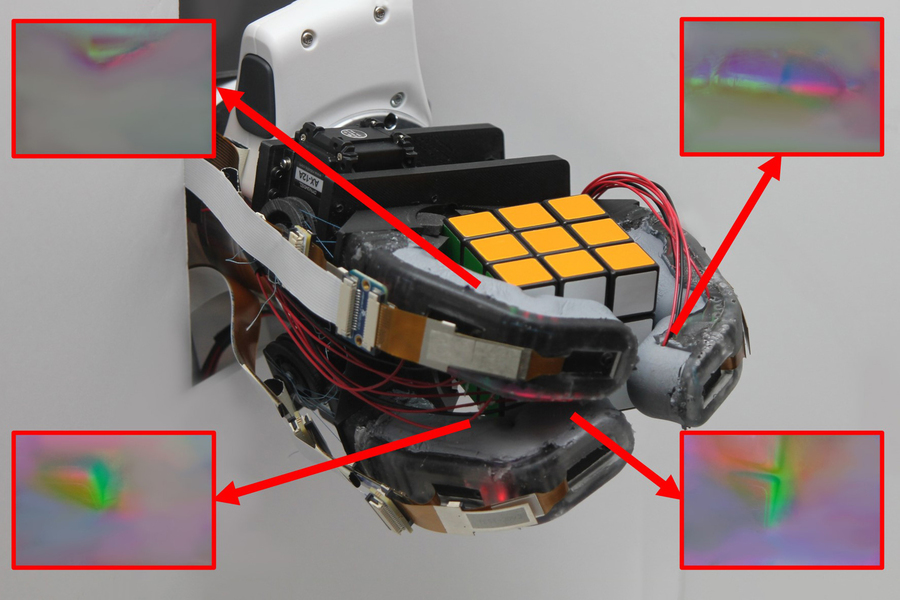

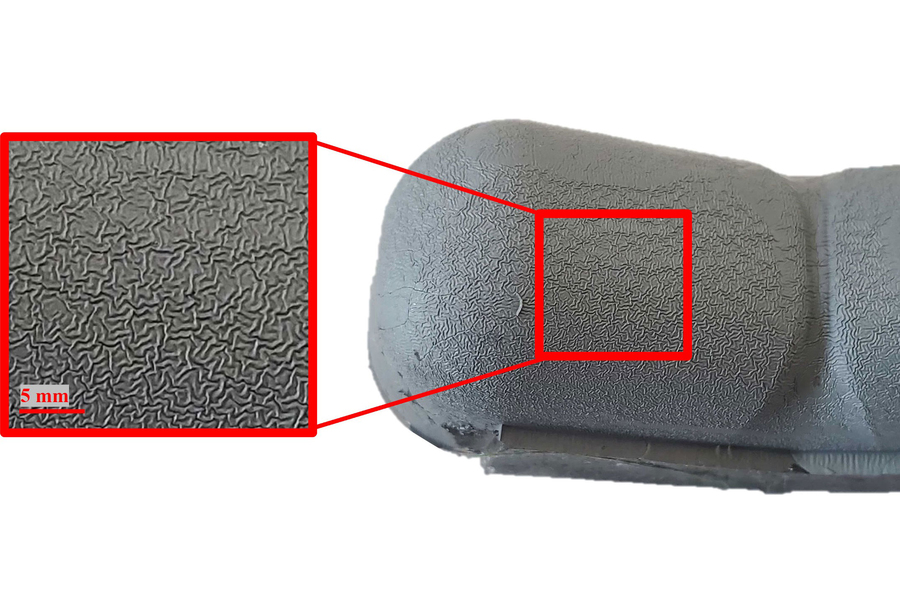

To test their approach, they designed a number of control experiments with different initial conditions. For instance, in some simulations, the autonomous agent needs to reach and stay inside a goal region while making drastic maneuvers to avoid obstacles that are on a collision course with it.

This video shows how the researchers used their technique to effectively fly a simulated jet aircraft in a scenario where it had to stabilize to a target near the ground while maintaining a very low altitude and staying within a narrow flight corridor. Courtesy of the researchers.

When compared with several baselines, their approach was the only one that could stabilize all trajectories while maintaining safety. To push their method even further, they used it to fly a simulated jet aircraft in a scenario one might see in a “Top Gun” movie. The jet had to stabilize to a target near the ground while maintaining a very low altitude and staying within a narrow flight corridor.

This simulated jet model was open-sourced in 2018 and had been designed by flight control experts as a testing challenge. Could researchers create a scenario that their controller could not fly? But the model was so complicated it was difficult to work with, and it still couldn’t handle complex scenarios, Fan says.

The MIT researchers’ controller was able to prevent the jet from crashing or stalling while stabilizing to the goal far better than any of the baselines.

In the future, this technique could be a starting point for designing controllers for highly dynamic robots that must meet safety and stability requirements, like autonomous delivery drones. Or it could be implemented as part of larger system. Perhaps the algorithm is only activated when a car skids on a snowy road to help the driver safely navigate back to a stable trajectory.

Navigating extreme scenarios that a human wouldn’t be able to handle is where their approach really shines, So adds.

“We believe that a goal we should strive for as a field is to give reinforcement learning the safety and stability guarantees that we will need to provide us with assurance when we deploy these controllers on mission-critical systems. We think this is a promising first step toward achieving that goal,” he says.

Moving forward, the researchers want to enhance their technique so it is better able to take uncertainty into account when solving the optimization. They also want to investigate how well the algorithm works when deployed on hardware, since there will be mismatches between the dynamics of the model and those in the real world.

“Professor Fan’s team has improved reinforcement learning performance for dynamical systems where safety matters. Instead of just hitting a goal, they create controllers that ensure the system can reach its target safely and stay there indefinitely,” says Stanley Bak, an assistant professor in the Department of Computer Science at Stony Brook University, who was not involved with this research. “Their improved formulation allows the successful generation of safe controllers for complex scenarios, including a 17-state nonlinear jet aircraft model designed in part by researchers from the Air Force Research Lab (AFRL), which incorporates nonlinear differential equations with lift and drag tables.”

The work is funded, in part, by MIT Lincoln Laboratory under the Safety in Aerobatic Flight Regimes program.