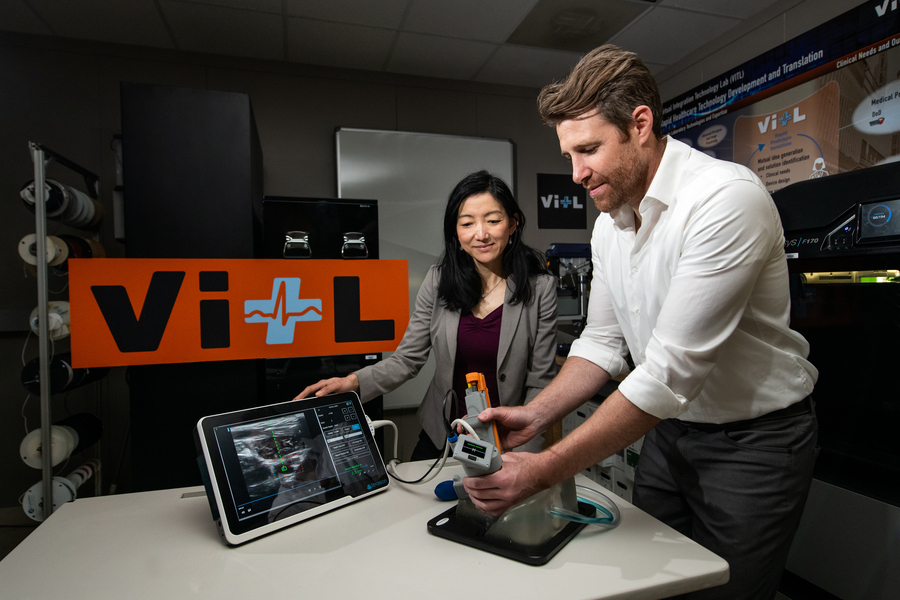

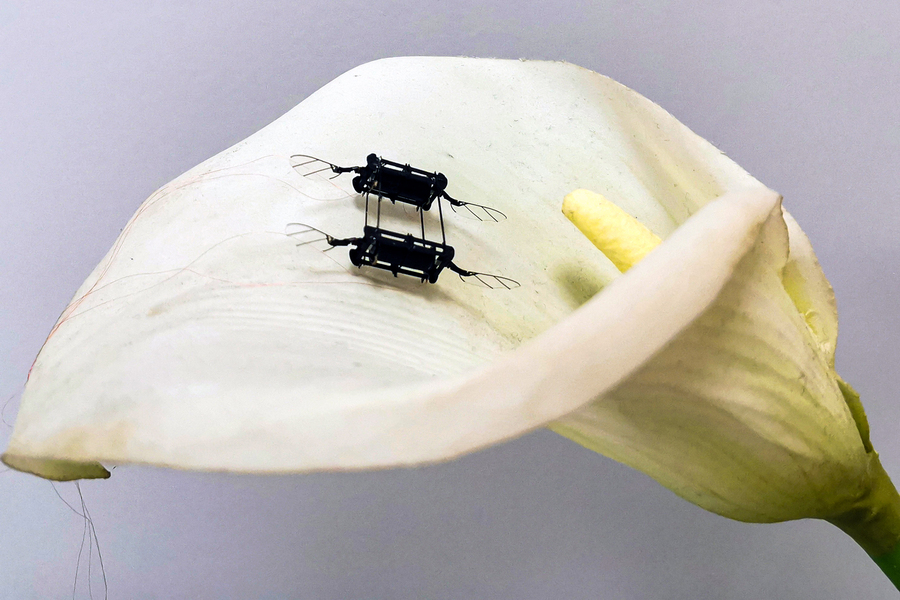

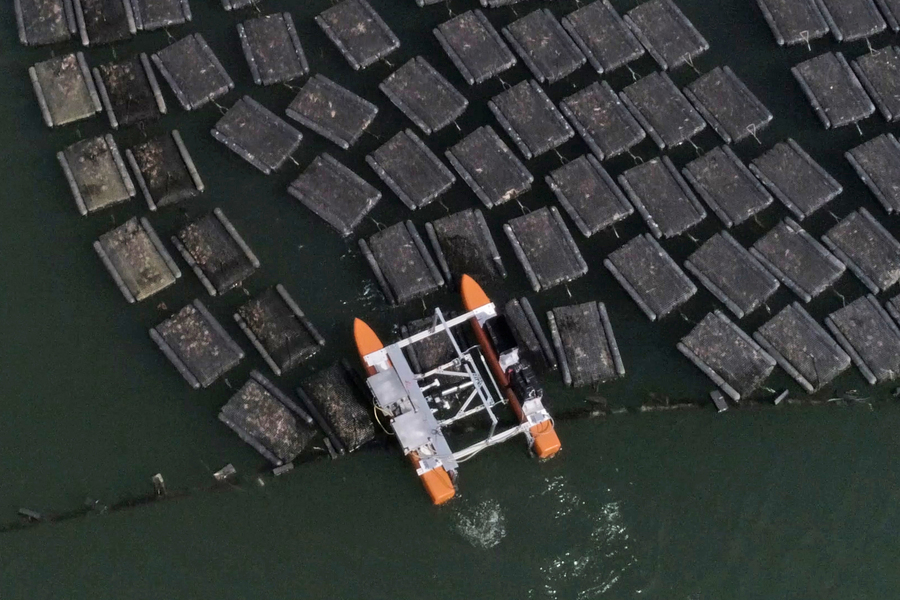

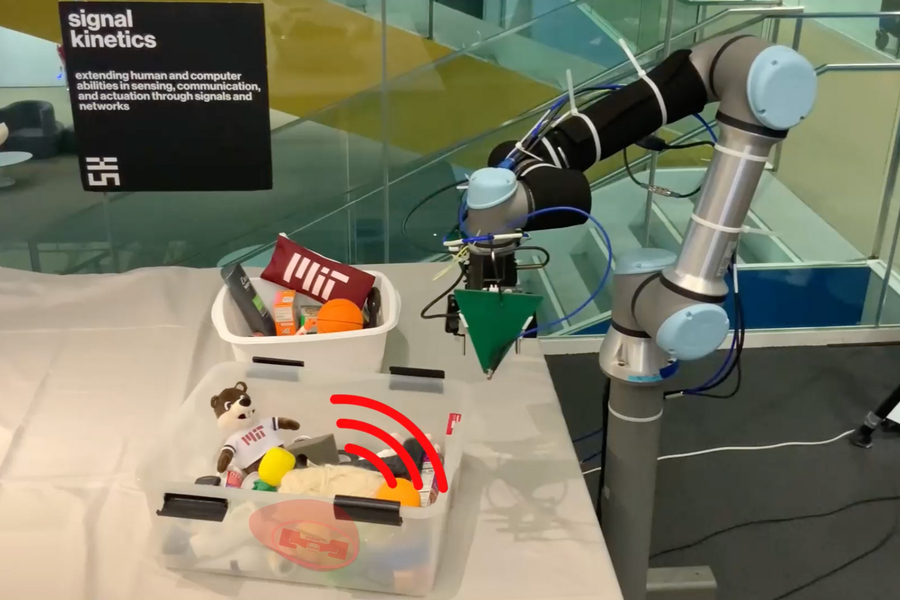

The robot seen here can’t see the human arm during the entire dressing process, yet it manages to successfully get a jacket sleeve pulled onto the arm. Photo courtesy of MIT CSAIL.

By Steve Nadis | MIT CSAIL

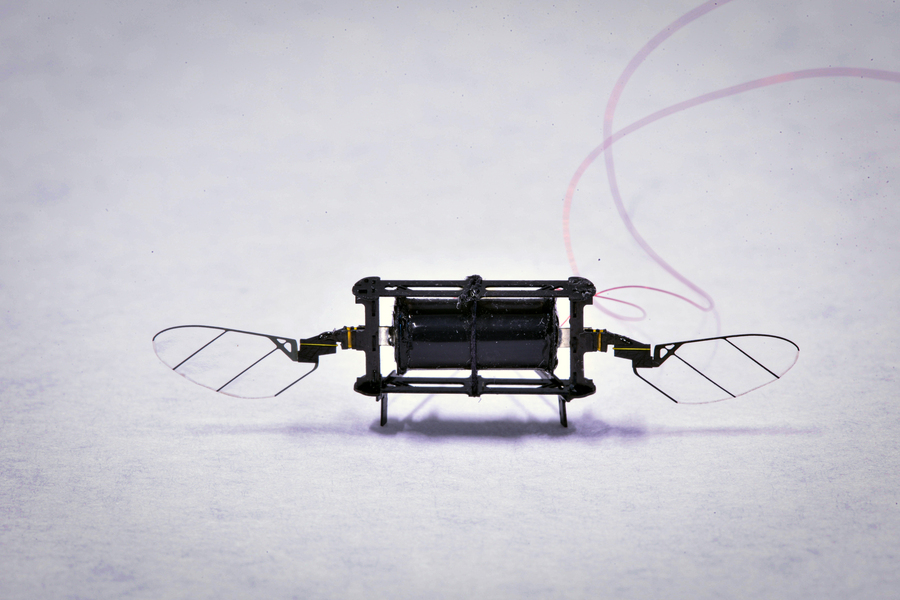

Robots are already adept at certain things, such as lifting objects that are too heavy or cumbersome for people to manage. Another application they’re well suited for is the precision assembly of items like watches that have large numbers of tiny parts — some so small they can barely be seen with the naked eye.

“Much harder are tasks that require situational awareness, involving almost instantaneous adaptations to changing circumstances in the environment,” explains Theodoros Stouraitis, a visiting scientist in the Interactive Robotics Group at MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL).

“Things become even more complicated when a robot has to interact with a human and work together to safely and successfully complete a task,” adds Shen Li, a PhD candidate in the MIT Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics.

Li and Stouraitis — along with Michael Gienger of the Honda Research Institute Europe, Professor Sethu Vijayakumar of the University of Edinburgh, and Professor Julie A. Shah of MIT, who directs the Interactive Robotics Group — have selected a problem that offers, quite literally, an armful of challenges: designing a robot that can help people get dressed. Last year, Li and Shah and two other MIT researchers completed a project involving robot-assisted dressing without sleeves. In a new work, described in a paper that appears in an April 2022 issue of IEEE Robotics and Automation, Li, Stouraitis, Gienger, Vijayakumar, and Shah explain the headway they’ve made on a more demanding problem — robot-assisted dressing with sleeved clothes.

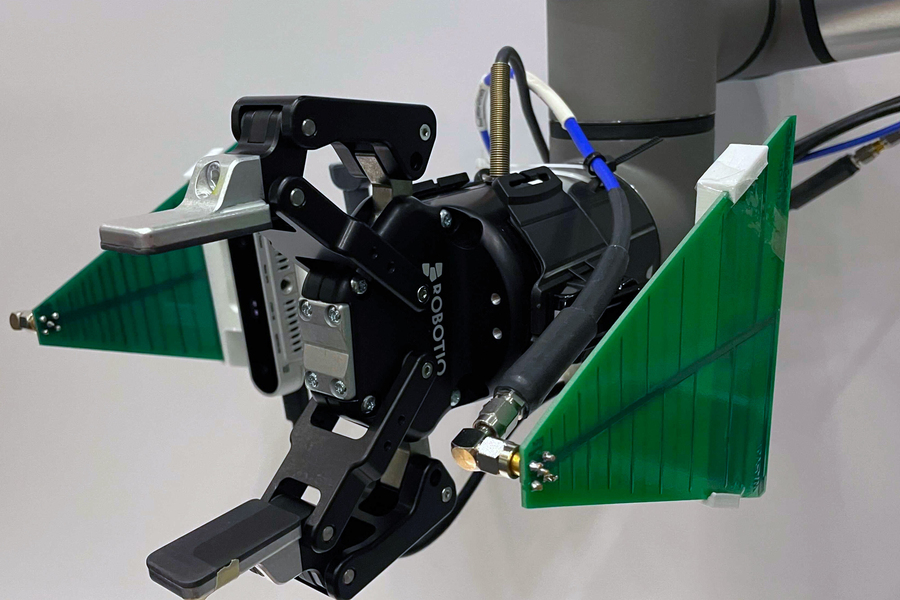

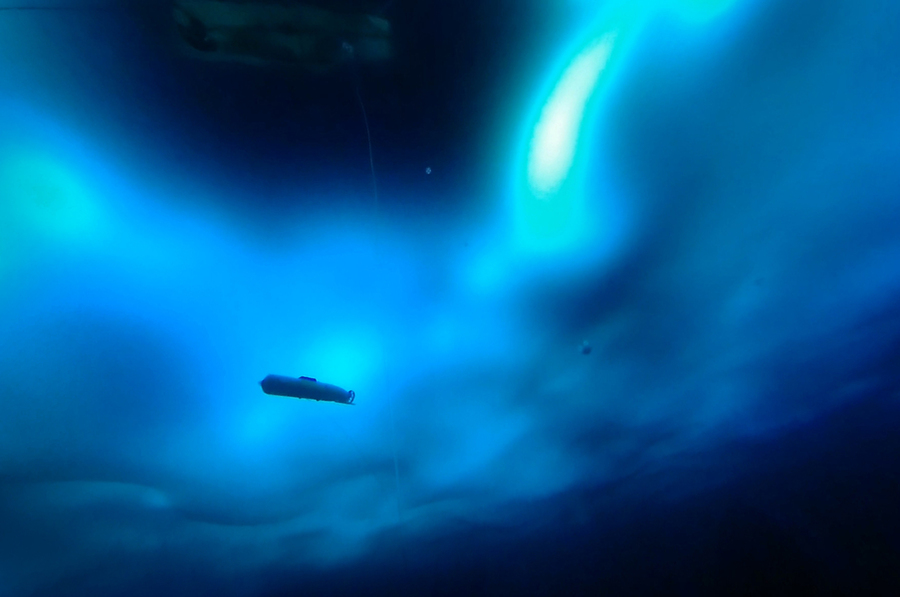

The big difference in the latter case is due to “visual occlusion,” Li says. “The robot cannot see the human arm during the entire dressing process.” In particular, it cannot always see the elbow or determine its precise position or bearing. That, in turn, affects the amount of force the robot has to apply to pull the article of clothing — such as a long-sleeve shirt — from the hand to the shoulder.

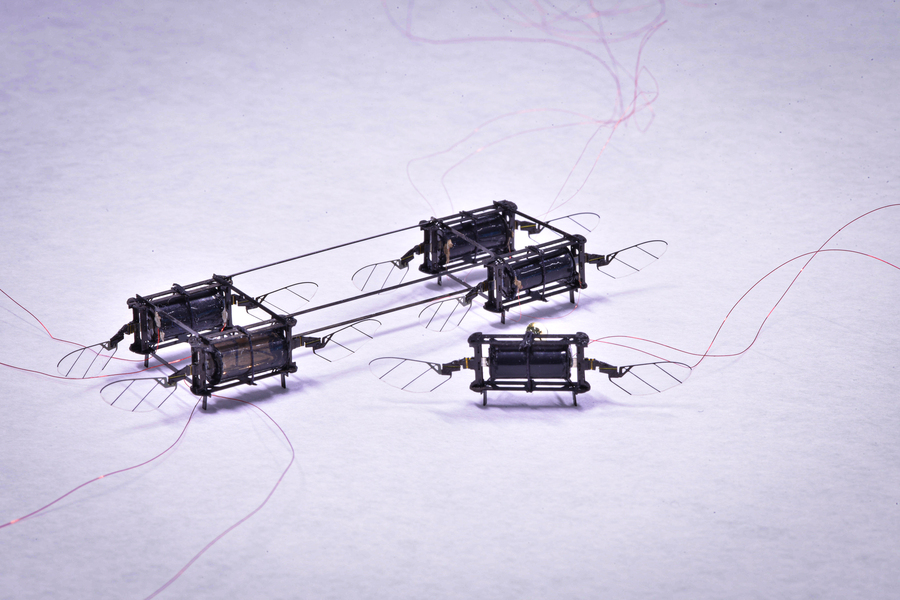

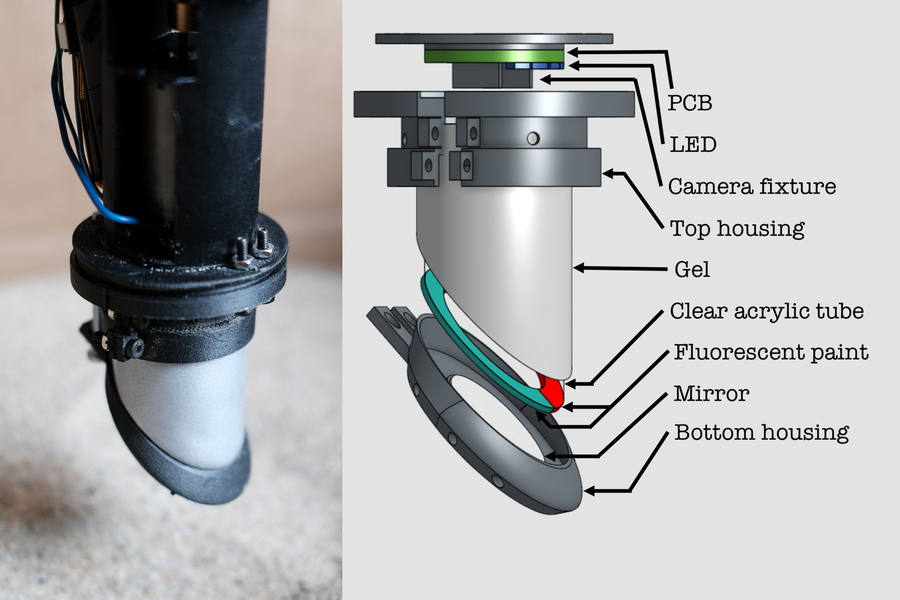

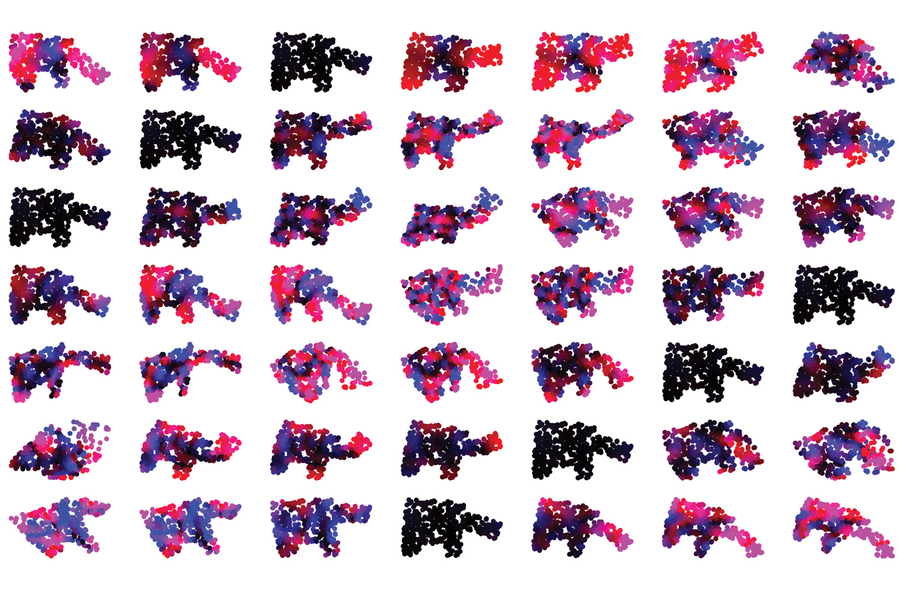

To deal with obstructed vision in trying to dress a human, an algorithm takes a robot’s measurement of the force applied to a jacket sleeve as input and then estimates the elbow’s position. Image: MIT CSAIL

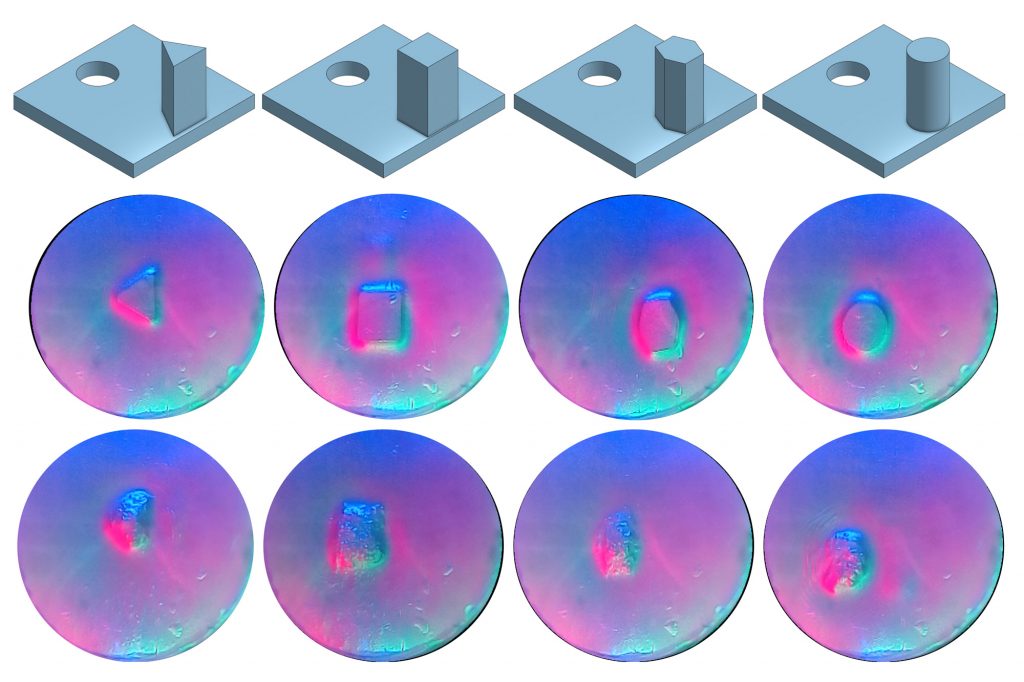

To deal with the issue of obstructed vision, the team has developed a “state estimation algorithm” that allows them to make reasonably precise educated guesses as to where, at any given moment, the elbow is and how the arm is inclined — whether it is extended straight out or bent at the elbow, pointing upwards, downwards, or sideways — even when it’s completely obscured by clothing. At each instance of time, the algorithm takes the robot’s measurement of the force applied to the cloth as input and then estimates the elbow’s position — not exactly, but placing it within a box or volume that encompasses all possible positions.

That knowledge, in turn, tells the robot how to move, Stouraitis says. “If the arm is straight, then the robot will follow a straight line; if the arm is bent, the robot will have to curve around the elbow.” Getting a reliable picture is important, he adds. “If the elbow estimation is wrong, the robot could decide on a motion that would create an excessive, and unsafe, force.”

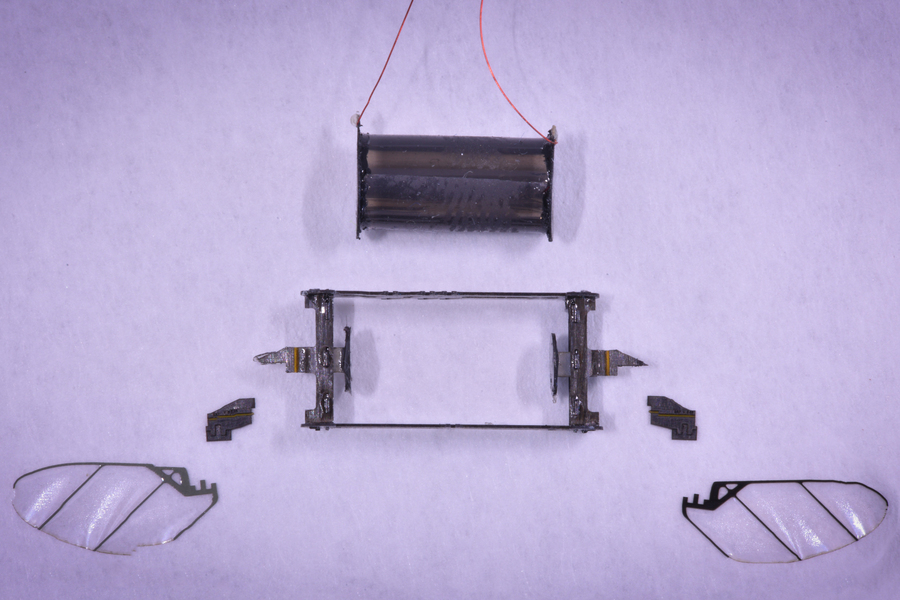

The algorithm includes a dynamic model that predicts how the arm will move in the future, and each prediction is corrected by a measurement of the force that’s being exerted on the cloth at a particular time. While other researchers have made state estimation predictions of this sort, what distinguishes this new work is that the MIT investigators and their partners can set a clear upper limit on the uncertainty and guarantee that the elbow will be somewhere within a prescribed box.

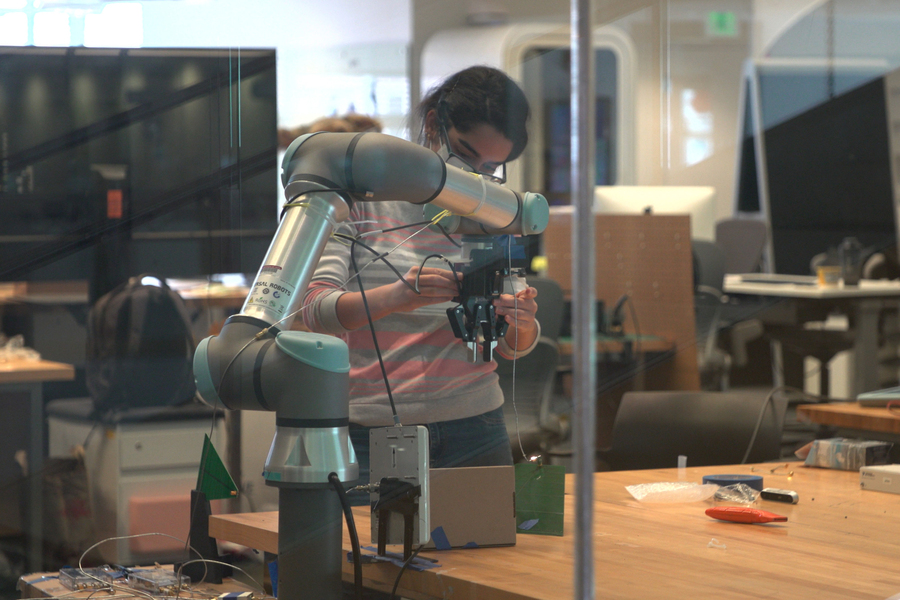

The model for predicting arm movements and elbow position and the model for measuring the force applied by the robot both incorporate machine learning techniques. The data used to train the machine learning systems were obtained from people wearing “Xsens” suits with built-sensors that accurately track and record body movements. After the robot was trained, it was able to infer the elbow pose when putting a jacket on a human subject, a man who moved his arm in various ways during the procedure — sometimes in response to the robot’s tugging on the jacket and sometimes engaging in random motions of his own accord.

This work was strictly focused on estimation — determining the location of the elbow and the arm pose as accurately as possible — but Shah’s team has already moved on to the next phase: developing a robot that can continually adjust its movements in response to shifts in the arm and elbow orientation.

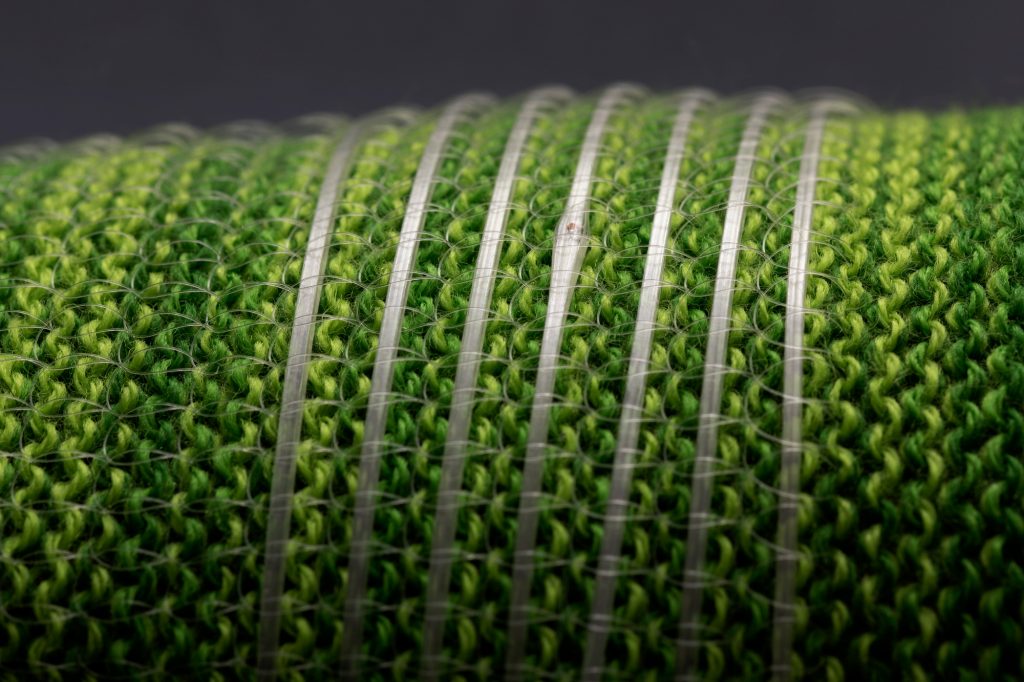

In the future, they plan to address the issue of “personalization” — developing a robot that can account for the idiosyncratic ways in which different people move. In a similar vein, they envision robots versatile enough to work with a diverse range of cloth materials, each of which may respond somewhat differently to pulling.

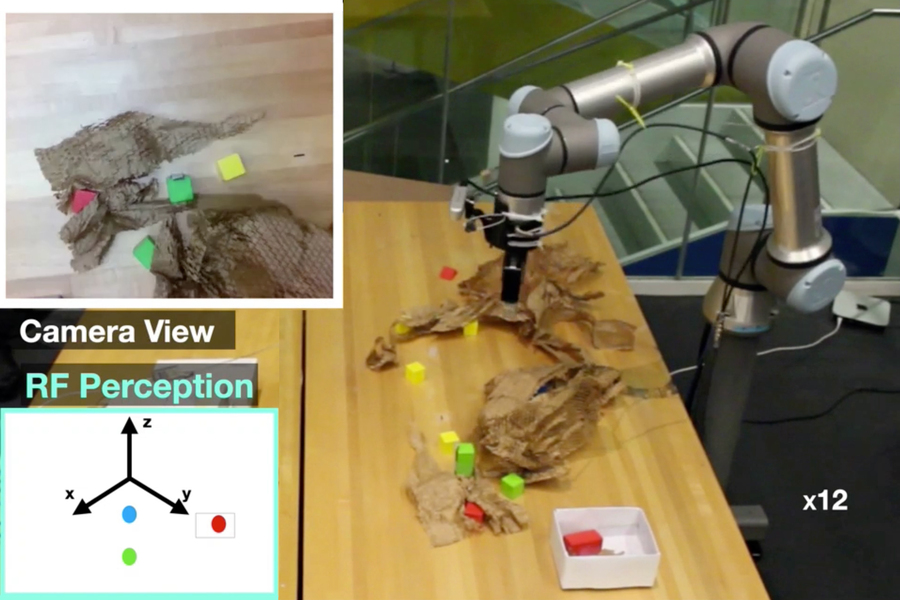

Although the researchers in this group are definitely interested in robot-assisted dressing, they recognize the technology’s potential for far broader utility. “We didn’t specialize this algorithm in any way to make it work only for robot dressing,” Li notes. “Our algorithm solves the general state estimation problem and could therefore lend itself to many possible applications. The key to it all is having the ability to guess, or anticipate, the unobservable state.” Such an algorithm could, for instance, guide a robot to recognize the intentions of its human partner as it works collaboratively to move blocks around in an orderly manner or set a dinner table.

Here’s a conceivable scenario for the not-too-distant future: A robot could set the table for dinner and maybe even clear up the blocks your child left on the dining room floor, stacking them neatly in the corner of the room. It could then help you get your dinner jacket on to make yourself more presentable before the meal. It might even carry the platters to the table and serve appropriate portions to the diners. One thing the robot would not do would be to eat up all the food before you and others make it to the table. Fortunately, that’s one “app” — as in application rather than appetite — that is not on the drawing board.

This research was supported by the U.S. Office of Naval Research, the Alan Turing Institute, and the Honda Research Institute Europe.