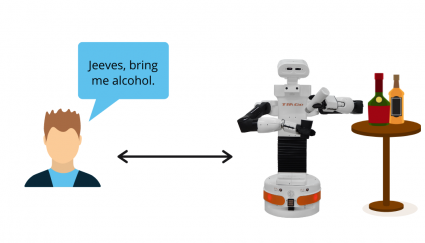

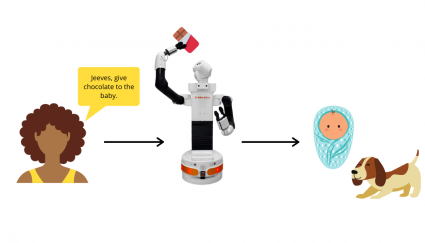

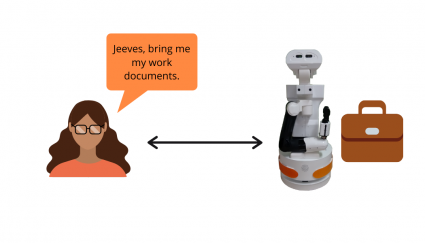

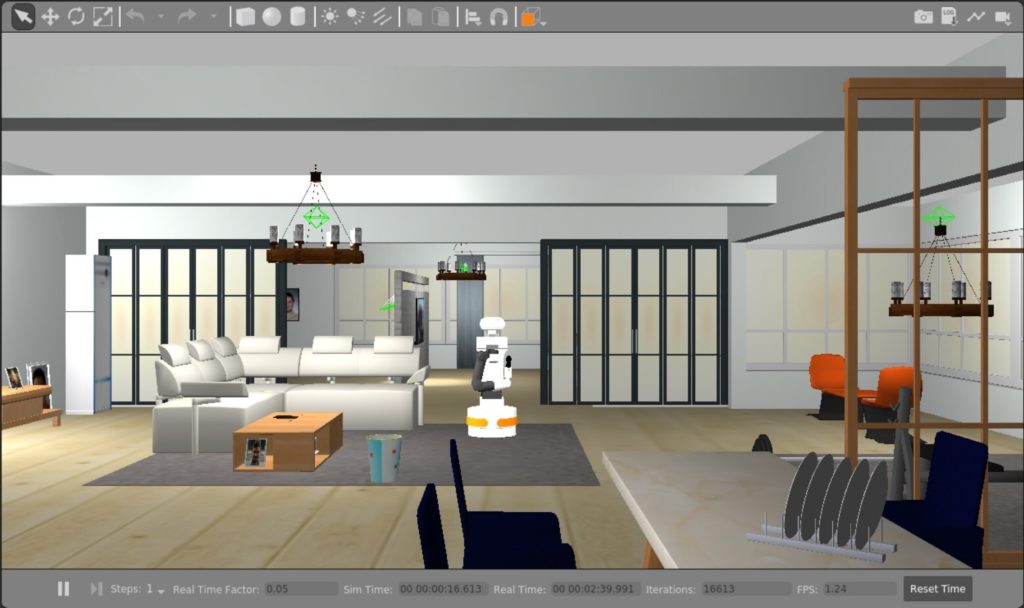

On August 8th, 2021, a team of four graduate students from the University of Toronto presented their ethical design in the world’s first ever roboethics competition, the RO-MAN 2021 Roboethics to Design & Development Competition. During the competition, design teams tackled a challenging yet relatable scenario—introducing a robot helper to the household. The students’ solution, entitled ”Jeeves, the Ethically Designed Interface (JEDI)”, demonstrated how home robots can act safely and according to social and cultural norms. Click here to watch their video submission. JEEVES acted as an extension of the mother and the interface rules accommodated her priorities. For example, the delivery of alcohol was prohibited when the mother was not home. Moreover, JEEVES was cautious about delivering hazardous material to minors and animals.

Judges from around the world, with diverse backgrounds ranging from industry professionals to lawyers and professors in ethics, gave their feedback on the team’s submission. Open Roboethics Institute also hosted an online opinion poll to hear what the general public thinks about the solution for this challenge. We polled 172 participants who were mostly from the U.S, as we used SurveyMonkey to get responses. Full results from the surveys can be found here.

I think that JEEVES suggests a reasonable and fair solution for the robot-human interactions that could happen in our everyday lives within a

household.RO-MAN Roboethics Competition Judge

The evaluation of JEEVES from the judges and the public was positive and yet critical.

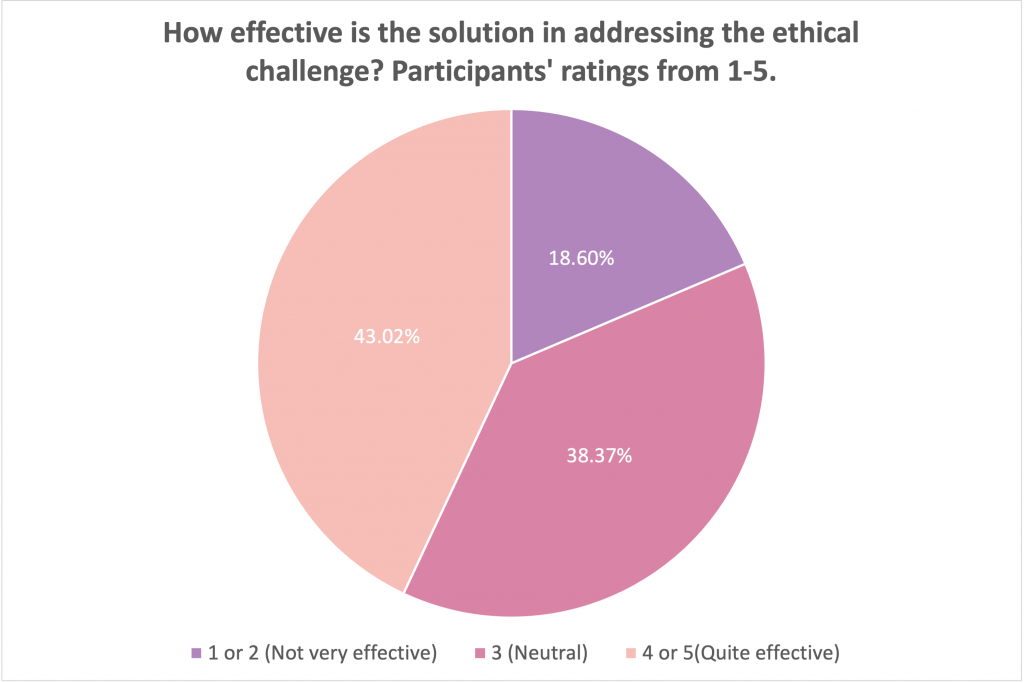

The judges generally felt that the team’s solution is understandable, accessible, and simple to implement. In our public opinion poll, the public also felt similarly about JEEVES. “I think that JEEVES suggests a reasonable and fair solution for the robot-human interactions that could happen in our everyday lives within a household”, said MinYoung Yoo, a PhD student studying Human-Computer Interaction at Simon Fraser University. “The three grounding principles are rock solid and [the robot’s] decisions meet moral expectations.” The public’s opinion echoed these thoughts. Of the 172 people we surveyed, around 43% felt that the solution was effective in addressing the ethical challenges posed by the home robot.

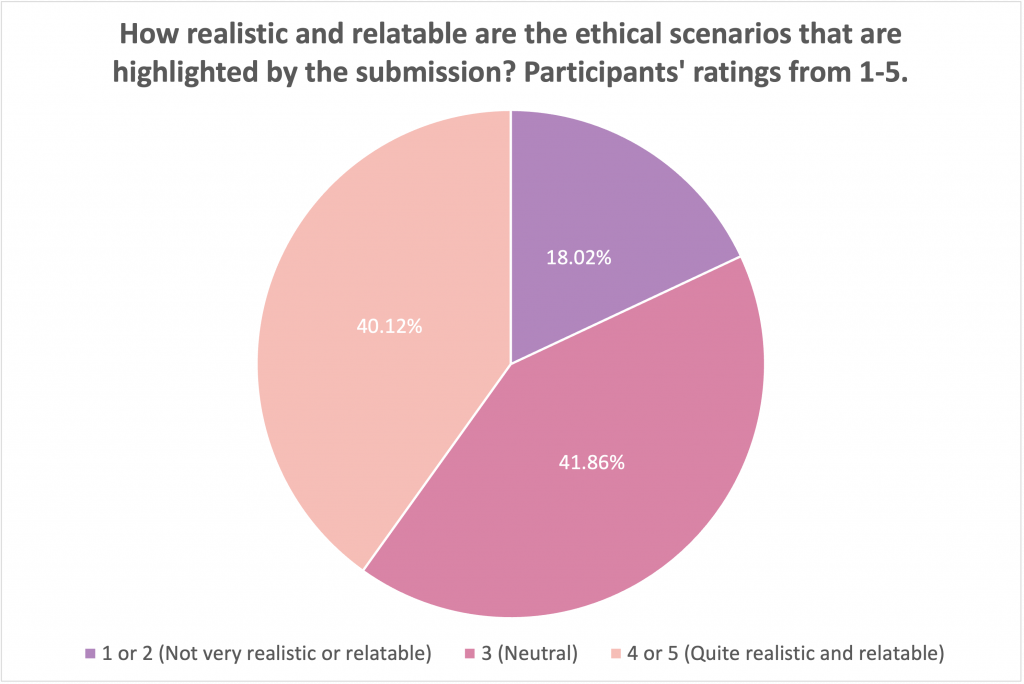

In addition, about 40% of respondents also evaluated the JEDI solution as realistic and relatable.

However, about 38 – 41% of the poll participants were indecisive about how effective or relatable the solution and about 18% thought it was neither effective or relatable. The judge’s discussion could inform why the participants had this perspective.

Concerns about JEEVES being limited in scope and not generalizable came up throughout the conversation with the judges. With any solution, it is really important to consider how the design would apply in a variety of different scenarios. Although this competition presents the challenge of how a robot may interact with a single-mother household, the judges asked what would happen if there was a second adult in the home. For example, if the mom had a long-term girlfriend and they bought the robot together, would the robot still defer to the mother for important decisions, such as when to give alcohol to the teenage daughter and her boyfriend? In another scenario, the mom purchases a new piece of jewellery for her daughter. This piece of jewellery is her birthday present and because of its size and its shape it could be hazardous for the dog and the baby. Should the robot deliver this item to the daughter if she asks for it while the dog and baby are in the room?

[The JEEVES solution] assumes a single owner and thus puts the responsibility on one person only. What happens when there are two parents and they disagree on things?

A public opinion poll participant

As reflected in the earlier scenario, a major topic of discussion was on ownership and who should be responsible for the robot’s decisions. A respondent of the public opinion poll was also worried about the ownership of the home robot: “[The JEEVES solution] assumes a single owner and thus puts the responsibility on one person only. What happens when there are two parents and they disagree on things?”

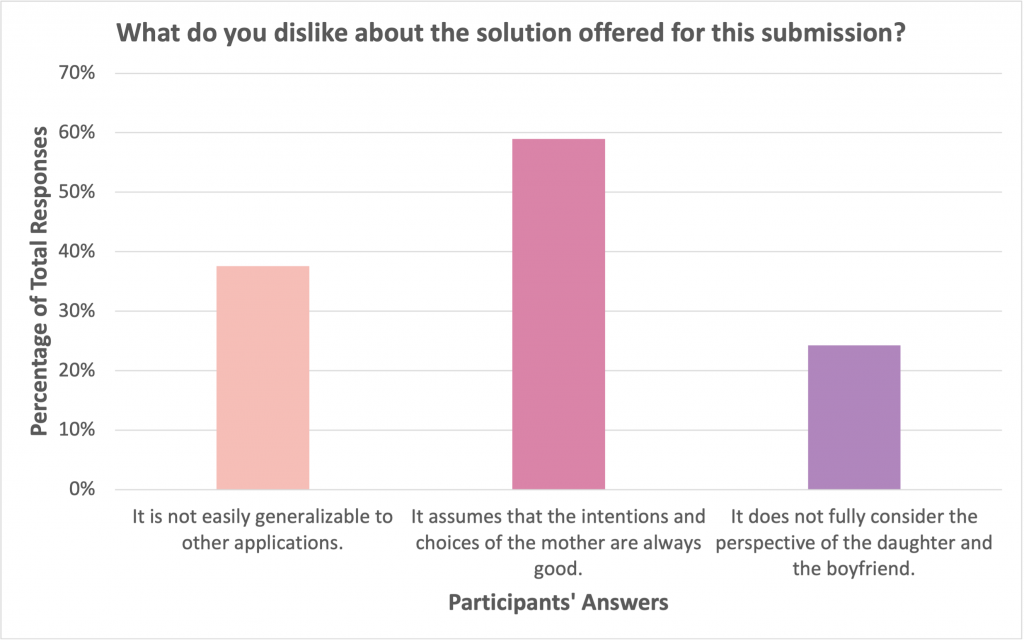

Timothy Lee, one of the judges and an industry expert in mechatronics, posed a similar worry, “What if the mother is intoxicated and makes the wrong call?” Placing the onus on only one individual to make the right decisions is risky. Correspondingly, a majority of the participants (about 60%) disliked that the solution assumes that the intentions and choices of the mother are always good. Interestingly, a smaller portion of participants thought that the daughter or boyfriend’s perspective should be taken into account. ORI had explored how ownership of a robot should affect a robot’s action in a previous poll, and it was clear that people were divided on what a robot should do based on ownership. Humans have a strong sense of ownership and this is reflected in law (ex. Product liability, company ownership, etc). How robotic platform ownership should be managed is a major research and legal question.

The crux of the JEEVES solution lies in the robot’s ability to categorize objects as harmless (i.e. food and water), hazardous, and personal possessions. However, how objects are categorized can change over time. Dr. Tae Wan Kim, a professor in business ethics, posed an interesting thought regarding the categorization of the mother’s gun. The team initially designed the robot to only give the gun to the mother and no other member of the household. However, Dr. Kim presented an interesting potential counterexample—what if an armed thief breaks into the house and the daughter needs the gun for self-defense? In this particular situation, should the robot give the gun to the daughter even though it is considered a hazardous object? Or perhaps, does it become more hazardous to not give the gun to the daughter? In response to this scenario, a member of the design team added that the baby will also grow up and certain objects will no longer be hazardous.

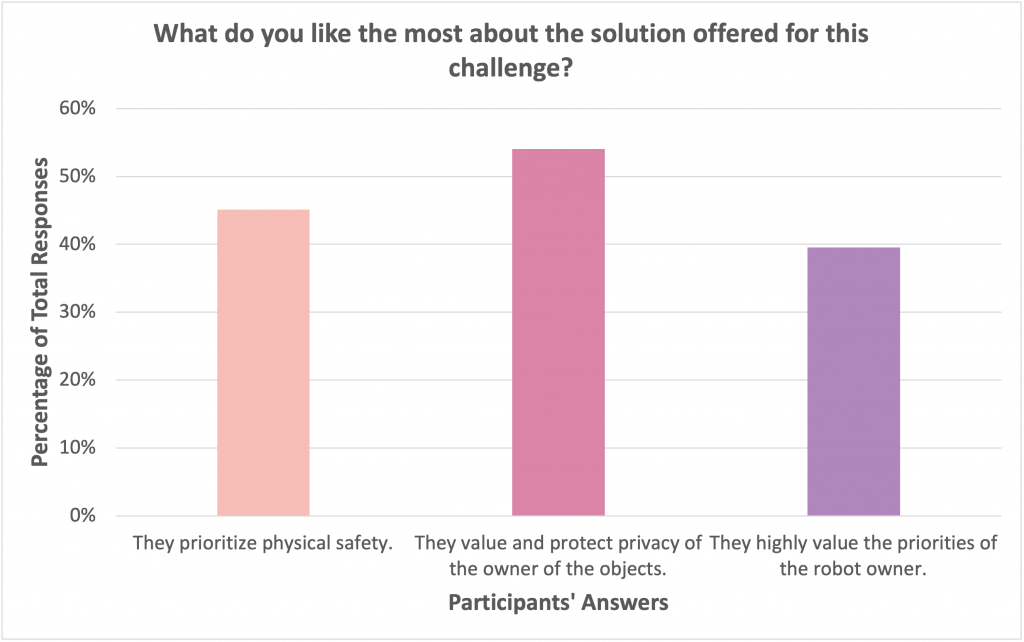

JEEVES ultimately prioritizes the safety of the household members in its ethical design, as reflected in the team’s report: “The first priority is the prevention of harm to users, the robot, and the environment.” Interestingly, the public seemed to have a slightly different opinion. The majority of poll respondents liked that the solution values and protects the privacy for the owner of the objects. In fact, more people seemed to value privacy over physical safety, which is a somewhat surprising result. But perhaps this is because the public doesn’t believe that the home robot can really cause physical harm. Alternatively, the public might be more concerned about their privacy considering the association between smart technologies and data breaches in the media over the past few years. Finally, It is important to highlight that all of the participants were from the United States or Canada where privacy is highly valued in society. Other cultures could have a very different perspective on which values should be prioritized.

Another notable point is that these ethical issues in robotics are exceptionally difficult to solve. “There’s no right answer, and that’s the beauty of itthere are just a whole bunch of answers with different reasoning that we can discuss”, said one of the judges at the end of the evaluation session. As reflected by our poll results where a significant number of people were unclear about how they felt, as well as the ongoing debates between experts in the field, and the judges’ open-ended comments, developing an ethical robot is an immense challenge. Any attempt is a commendable feat—and JEEVES is an excellent start.

There’s no right answer, and that’s the beauty of itthere are just a whole bunch of answers with different reasoning that we can discuss.

RO-MAN Roboethics Competition Judge