WeRobotics Global has become a premier forum for social good robotics. The feedback featured below was unsolicited. On June 1, 2017, we convened our first, annual global event, bringing together 34 organizations to New York City (full list below) to shape the global agenda and future use of robotics in the social good sector. WeRobotics Global was kindly hosted by the Rockefeller Foundation, the first donor to support our efforts. They opened the event with welcome remarks and turned it over to Patrick Meier from WeRobotics who provided an overview of WeRobotics and the big picture context for social sector robotics.

I’ve been to countless remote sensing conferences over the past 30 years but WeRobotics Global absolutely ranks as the best event I’ve been to – Remote Sensing Expert

The event was really mind-blowing. I’ve participated in many workshops over the past 20 years. WeR Global was by far the most insightful and practical. It is also amazing how closely together everyone is working — irrespective of who is working where (NGO, UN, private sector, donor). I’ve never seen such a group of people come together this away. – Humanitarian Professional

WeRobotics Global is completely different to any development meeting or workshop I’ve been to in recent years. The discussions flowed seamlessly between real world challenges, genuine bottom-up approaches and appropriate technology solutions. Conversations were always practical and strikingly transparent. This was a highly unusual event. – International Donor

The first panel featured our Flying Labs Coordinators from Tanzania (Yussuf), Peru (Juan) and Nepal (Uttam). Each shared the hard work they’ve been doing over the past 6-10 months on localizing and applying robotics solutions. Yussuf spoke about the lab’s use of aerial robotics for disaster damage assessment following the earthquake in Bukoba and for coastal monitoring, environmental monitoring and forestry management. He emphasized the importance of community engagement and closed with new projects that Tanzania Flying Labs is working on such as mangrove monitoring for the Department of Forestry. Juan presented the work of the labs in the Amazon Rainforest, which is a joint effort with the Peruvian Ministry of Health. Together, they are field-testing the use of affordable and locally repairable flying robots for the delivery of antivenom and other medical payload between local clinics and remote villages. Juan noted that Peru Flying Labs is gearing up to carry out a record number of flight tests this summer using a larger and more diverse fleet of flying robots. Last but not least, Uttam showed how Nepal Flying Labs has been using flying robots for agriculture monitoring, damage assessment and mapping of property rights. He also gave an overview of the social entrepreneurship training and business plan competition recently organized by Nepal Flying Labs. This business incubation training has resulted in the launch of 4 new Nepali start-up companies focused on Robotics-as-a-Service.

The following images provide highlights from each of our Flying Labs: Tanzania, Peru and Nepal.

The second panel featured talks on sector based solutions starting with the International Federation of the Red Cross (IFRC). The Federation (Aarathi) spoke about their joint project with WeRobotics; looking at cross-sectoral needs for various robotics solutions in the South Pacific. IFRC is exploring at the possibility of launching a South Pacific Flying Labs with a strong focus on women and girls. Pix4D (Lorenzo) addressed the role of aerial robotics in agriculture, giving concrete examples of successful applications while providing guidance to our Flying Labs Coordinators. The Wall Street Journal (Sally) spoke about the use of aerial robotics in news gathering and investigative journalism. She specifically emphasized the importance of using flying robots for storytelling. Duke Marine Labs (David) closed the panel with an overview of their projects in nature conservation and marine life protection, highlighting their use of machine learning for automated feature detection for real-time analysis.

The second panel featured talks on sector based solutions starting with the International Federation of the Red Cross (IFRC). The Federation (Aarathi) spoke about their joint project with WeRobotics; looking at cross-sectoral needs for various robotics solutions in the South Pacific. IFRC is exploring at the possibility of launching a South Pacific Flying Labs with a strong focus on women and girls. Pix4D (Lorenzo) addressed the role of aerial robotics in agriculture, giving concrete examples of successful applications while providing guidance to our Flying Labs Coordinators. The Wall Street Journal (Sally) spoke about the use of aerial robotics in news gathering and investigative journalism. She specifically emphasized the importance of using flying robots for storytelling. Duke Marine Labs (David) closed the panel with an overview of their projects in nature conservation and marine life protection, highlighting their use of machine learning for automated feature detection for real-time analysis.

Panel number three addressed the transformation of transportation. UNICEF (Judith) highlighted the field tests they have been carrying out in Malawi; using cargo robotics to transport HIV samples in order to accelerate HIV testing and thus treatment. UNICEF has also launched an air corridor in Malawi to enable further field-testing of flying robots. MSF (Oriol) shared their approach to cargo delivery using aerial robotics. They shared examples from Papua New Guinea (PNG) and emphasized the importance of localizing appropriate robotics solutions that can be maintained locally. MSF also called for the launch of PNG Flying Labs. IAEA was unable to attend WeR Global, so Patrick and Adam from WeRobotics gave the talk instead. WeRobotics is teaming up with IAEA to design and test a release mechanism for sterilized mosquitos in order to reduce the incidence of Zika and other mosquito-borne illnesses. More here. Finally, Llamasoft (Sid) closed the panel with a strong emphasis on the need to collect and share structured data to accurately carry out comparative cost-benefit-analyses of cargo delivery via flying robots versus conventional means. Sid used the analogy of self-driving cars to highlight how problematic the current lack of data vis-a-vis reliably evaluating the impact of cargo robotics.

Panel number three addressed the transformation of transportation. UNICEF (Judith) highlighted the field tests they have been carrying out in Malawi; using cargo robotics to transport HIV samples in order to accelerate HIV testing and thus treatment. UNICEF has also launched an air corridor in Malawi to enable further field-testing of flying robots. MSF (Oriol) shared their approach to cargo delivery using aerial robotics. They shared examples from Papua New Guinea (PNG) and emphasized the importance of localizing appropriate robotics solutions that can be maintained locally. MSF also called for the launch of PNG Flying Labs. IAEA was unable to attend WeR Global, so Patrick and Adam from WeRobotics gave the talk instead. WeRobotics is teaming up with IAEA to design and test a release mechanism for sterilized mosquitos in order to reduce the incidence of Zika and other mosquito-borne illnesses. More here. Finally, Llamasoft (Sid) closed the panel with a strong emphasis on the need to collect and share structured data to accurately carry out comparative cost-benefit-analyses of cargo delivery via flying robots versus conventional means. Sid used the analogy of self-driving cars to highlight how problematic the current lack of data vis-a-vis reliably evaluating the impact of cargo robotics.

The fourth and final panel went beyond aerial robotics. Digger (Thomas) showed how they convert heavy construction vehicles into semi-autonomous platforms to clear landmines and debris in conflict zones like Iraq and Syria. Science in the Wild (Ulyana) was alas unable to attend the event, so Patrick from WeRobotics gave the talk instead. This focused on the use of swimming robots to monitor glacial lakes in the Himalaya. The purpose of the effort is to identify cracks in the lake floors before they trigger what local villagers call the tsunamis of the Himalaya. OpenROV (David) gave a talk on the use of diving robots, sharing real-world examples and providing exciting updates on the new Trident diving robot. Planet Labs (Andrew) gave the closing talk, highlighting how space robotics (satellites) are being used across a wide range of social good projects. He emphasized the importance of integrating both aerial and satellite imagery to support social good projects.

The final session at WeR Global comprised breakout groups to identify next steps for WeRobotics and the social good sector more broadly. Many quality insights and recommendations were shared during the report back. One such recommendation was to hold WeR Global again, and sooner rather than later. So we look forward to organizing WeRobotics Global 2018. We will be providing updates via our blog and email list. We will also use our blog and email list to share select videos of the individual talks from Global 2017 along with their respective slide decks.

In the meantime, a big thanks to all participants and speakers for making Global 2017 such an unforgettable event. And sincerest thanks to the Rockefeller Foundation for hosting us at their headquarters in New York City.

Mosquitos kill more humans every year than any other animal on the planet and conventional methods to reduce mosquito-borne illnesses haven’t worked as well as many hoped. So we’ve been hard at work since receiving this USAID grant six months ago to reduce Zika incidence and related threats to public health.

Mosquitos kill more humans every year than any other animal on the planet and conventional methods to reduce mosquito-borne illnesses haven’t worked as well as many hoped. So we’ve been hard at work since receiving this USAID grant six months ago to reduce Zika incidence and related threats to public health.

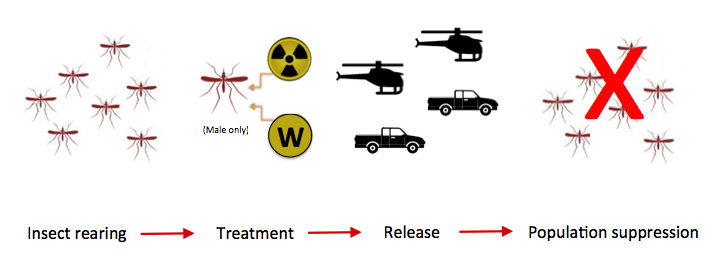

Our approach seeks to complement and extend (not replace) these existing delivery methods. The challenge with manned aircraft is that they are expensive to operate and maintain. They may also not be able to target areas with great accuracy given the altitudes they have to fly at.

Our approach seeks to complement and extend (not replace) these existing delivery methods. The challenge with manned aircraft is that they are expensive to operate and maintain. They may also not be able to target areas with great accuracy given the altitudes they have to fly at. Cars are less expensive, but they rely on ground infrastructure. This can be a challenge in some corners of the world when roads become unusable due to rainy seasons or natural disasters. What’s more, not everyone lives on or even close to a road.

Cars are less expensive, but they rely on ground infrastructure. This can be a challenge in some corners of the world when roads become unusable due to rainy seasons or natural disasters. What’s more, not everyone lives on or even close to a road. Our IAEA colleagues thus envision establishing small mosquito breeding labs in strategic regions in order to release sterilized male mosquitos and reduce the overall mosquito population in select hotspots. The idea would be to use both ground and aerial release methods with cars and flying robots.

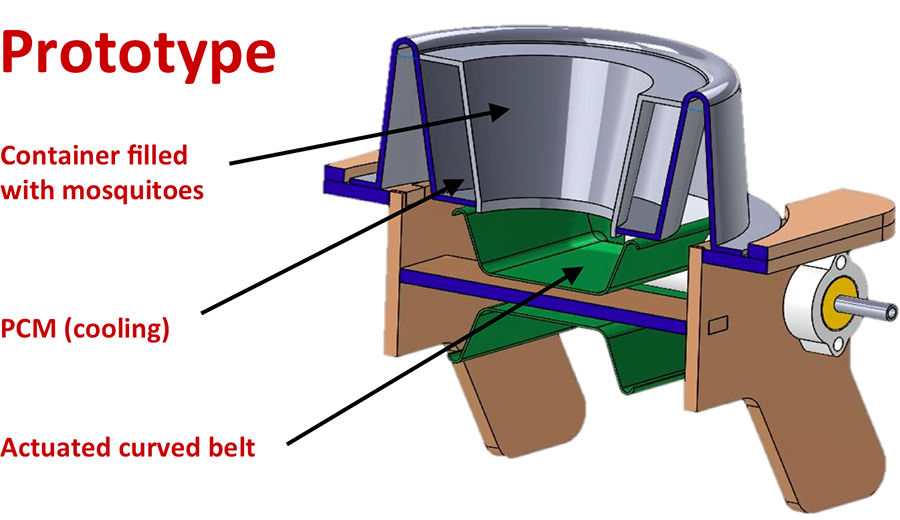

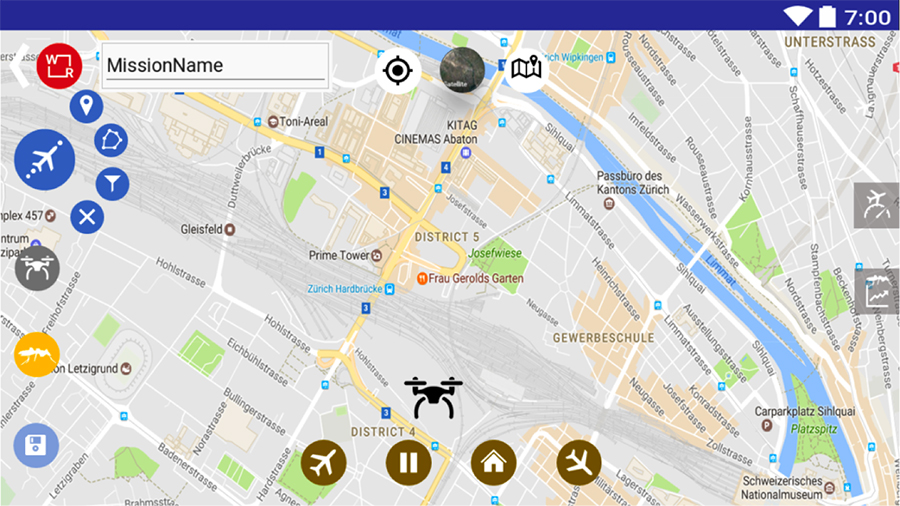

Our IAEA colleagues thus envision establishing small mosquito breeding labs in strategic regions in order to release sterilized male mosquitos and reduce the overall mosquito population in select hotspots. The idea would be to use both ground and aerial release methods with cars and flying robots. The real technical challenge here, besides breeding millions of sterilized mosquitos, is actually not the flying robot (drone/UAV) but rather the engineering that needs to go into developing a release mechanism that attaches to the flying robot. In fact, we’re more interested in developing a release mechanism that will work with any number of flying robots, rather than having a mechanism work with one and only one drone/UAV. Aerial robotics is evolving quickly and it is inevitable that drones/UAVs available in 6-12 months will have greater range and payload capacity than today. So we don’t want to lock our release mechanism into a platform that may be obsolete by the end of the year. So for now we’re just using a DJI Matrice M600 Pro so we can focus on engineering the release mechanism.

The real technical challenge here, besides breeding millions of sterilized mosquitos, is actually not the flying robot (drone/UAV) but rather the engineering that needs to go into developing a release mechanism that attaches to the flying robot. In fact, we’re more interested in developing a release mechanism that will work with any number of flying robots, rather than having a mechanism work with one and only one drone/UAV. Aerial robotics is evolving quickly and it is inevitable that drones/UAVs available in 6-12 months will have greater range and payload capacity than today. So we don’t want to lock our release mechanism into a platform that may be obsolete by the end of the year. So for now we’re just using a DJI Matrice M600 Pro so we can focus on engineering the release mechanism. Developing this release mechanism is anything but trivial. Ironically, mosquitos are particularly fragile. So if they get damaged while being released, game over. What’s more, in order to pack one million mosquitos (about 2.5kg in weight) into a particularly confined space, they need to be chilled or else they’ll get into a brawl and damage each other, i.e., game over. (Recall the last time you were stuck in the middle seat in Economy class on a transcontinental flight). This means that the release mechanism has to include a reliable cooling system. But wait, there’s more. We also need to control the rate of release, i.e., to control how many thousands mosquitos are released per unit of space and time in order to drop said mosquitos in a targeted and homogenous manner. Adding to the challenge is the fact that mosquitos need time to unfreeze during free fall so they can fly away and do their thing, i.e., before they hit the ground or else, game over.

Developing this release mechanism is anything but trivial. Ironically, mosquitos are particularly fragile. So if they get damaged while being released, game over. What’s more, in order to pack one million mosquitos (about 2.5kg in weight) into a particularly confined space, they need to be chilled or else they’ll get into a brawl and damage each other, i.e., game over. (Recall the last time you were stuck in the middle seat in Economy class on a transcontinental flight). This means that the release mechanism has to include a reliable cooling system. But wait, there’s more. We also need to control the rate of release, i.e., to control how many thousands mosquitos are released per unit of space and time in order to drop said mosquitos in a targeted and homogenous manner. Adding to the challenge is the fact that mosquitos need time to unfreeze during free fall so they can fly away and do their thing, i.e., before they hit the ground or else, game over. We’ve already started testing our early prototype using “mosquito substitutes” like cumin and anise as the latter came recommended by mosquito experts. Next month, we’ll be at the FAO/IAEA Pest Control Lab in Vienna to test the release mechanism indoors using dead and live mosquitos. We’ll then have 3 months to develop a second version of the prototype before heading to Latin America to field test the release mechanism with our Peru Flying Labs. One of these tests will involve the the integration of the flying robot and the release mechanism in terms of both hardware and software. In other words, we’ll be testing the integrated system over different types of terrain and weather conditions in Peru specifically.

We’ve already started testing our early prototype using “mosquito substitutes” like cumin and anise as the latter came recommended by mosquito experts. Next month, we’ll be at the FAO/IAEA Pest Control Lab in Vienna to test the release mechanism indoors using dead and live mosquitos. We’ll then have 3 months to develop a second version of the prototype before heading to Latin America to field test the release mechanism with our Peru Flying Labs. One of these tests will involve the the integration of the flying robot and the release mechanism in terms of both hardware and software. In other words, we’ll be testing the integrated system over different types of terrain and weather conditions in Peru specifically.

For now, though, our WeRobotics Engineering Team (below) is busy developing the prototype out of our Zurich office. So if you happen to be passing through, definitely let us know, we’d love to show you the latest and give you a demo. We’ll also be reaching out the Technical University of Peru who are members of our Peru Flying Labs to engage with their engineers as we get closer to the field tests in country.

For now, though, our WeRobotics Engineering Team (below) is busy developing the prototype out of our Zurich office. So if you happen to be passing through, definitely let us know, we’d love to show you the latest and give you a demo. We’ll also be reaching out the Technical University of Peru who are members of our Peru Flying Labs to engage with their engineers as we get closer to the field tests in country. As an aside, our USAID colleagues recently encouraged us to consider an entirely separate, follow up project totally independently of IAEA whereby we’d be giving rides to Wolbachia treated mosquitos. Wolbachia is the name of bacteria that is used to infect male mosquitos so they can’t reproduce. IAEA does not focus on Wolbachia at all, but other USAID grantees do. Point being, the release mechanism could have multiple applications. For example, instead of releasing mosquitos, the mechanism could scatter seeds. Sound far-fetched?

As an aside, our USAID colleagues recently encouraged us to consider an entirely separate, follow up project totally independently of IAEA whereby we’d be giving rides to Wolbachia treated mosquitos. Wolbachia is the name of bacteria that is used to infect male mosquitos so they can’t reproduce. IAEA does not focus on Wolbachia at all, but other USAID grantees do. Point being, the release mechanism could have multiple applications. For example, instead of releasing mosquitos, the mechanism could scatter seeds. Sound far-fetched?