In an OpEd piece in the NY Times, and in a TED Talk late last year, Oren Etzioni, PhD, author, and CEO of the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence, suggested an update for Isaac Asimov’s three laws of Artificial Intelligence. Given the widespread media attention emanating from Elon Musk’s (and others) warnings, these updates might be worth reviewing.

In an OpEd piece in the NY Times, and in a TED Talk late last year, Oren Etzioni, PhD, author, and CEO of the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence, suggested an update for Isaac Asimov’s three laws of Artificial Intelligence. Given the widespread media attention emanating from Elon Musk’s (and others) warnings, these updates might be worth reviewing.

The Warnings

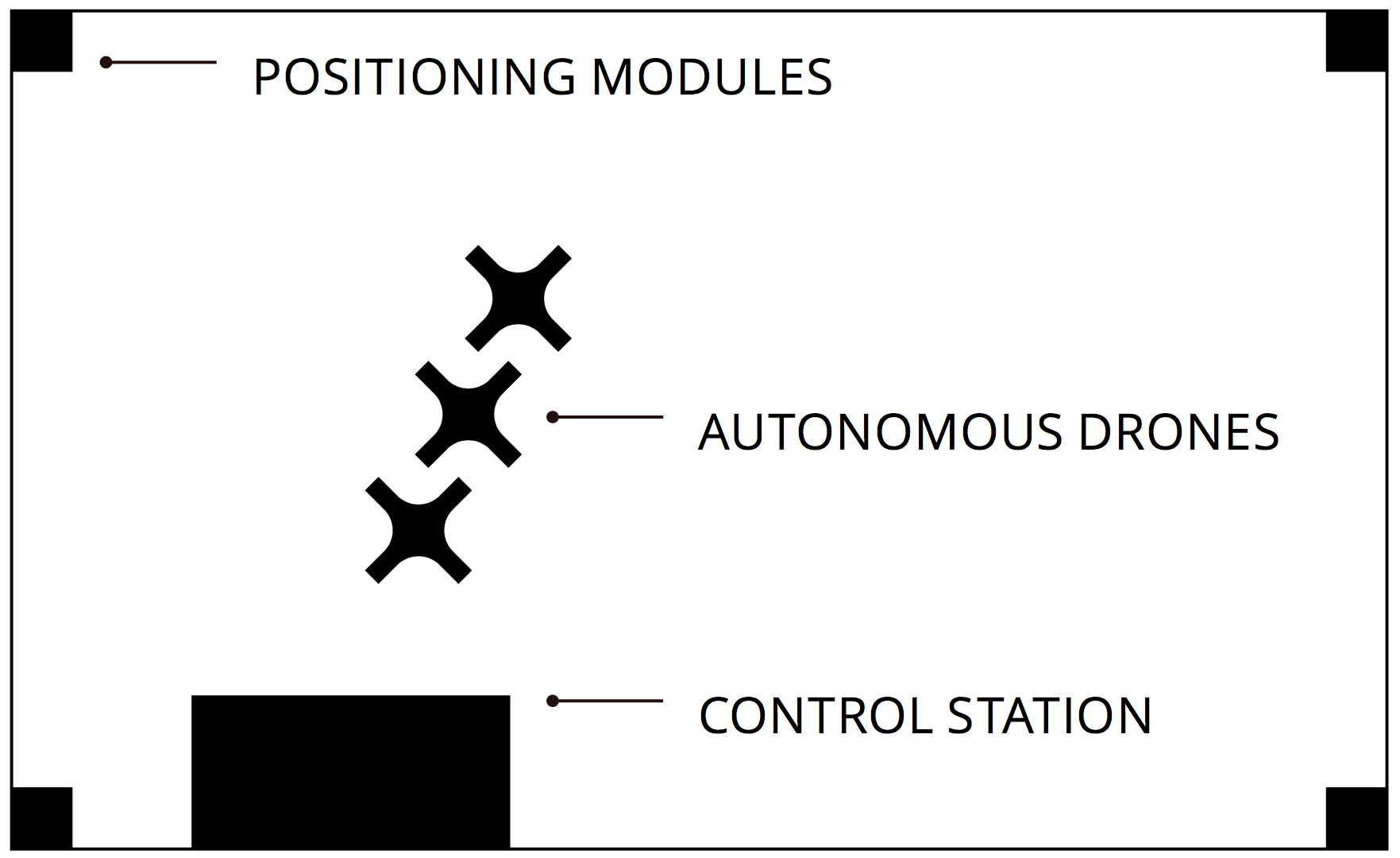

In an open letter to the U.N., a group of specialists from 26 nations and led by Elon Musk called for the United Nations to ban the development and use of autonomous weapons. The signatories included Musk and DeepMind co-founder Mustafa Suleyman, as well as 100+ other leaders in robotics and artificial-intelligence companies. They write that AI technology has reached a point where the deployment of such systems in the form of autonomous weapons is feasible within years, not decades, and many in the defense industry are saying that autonomous weapons will be the third revolution in warfare, after gunpowder and nuclear arms.

In an open letter to the U.N., a group of specialists from 26 nations and led by Elon Musk called for the United Nations to ban the development and use of autonomous weapons. The signatories included Musk and DeepMind co-founder Mustafa Suleyman, as well as 100+ other leaders in robotics and artificial-intelligence companies. They write that AI technology has reached a point where the deployment of such systems in the form of autonomous weapons is feasible within years, not decades, and many in the defense industry are saying that autonomous weapons will be the third revolution in warfare, after gunpowder and nuclear arms.

Another more political warning was recently broadcast on VoA: Russian President Vladimir Putin, speaking to a group of Russian students, called artificial intelligence “not only Russia’s future but the future of the whole of mankind… The one who becomes the leader in this sphere will be the ruler of the world. There are colossal opportunities and threats that are difficult to predict now.”

Asimov’s Three Rules

Isaac Asimov wrote “Runaround” in 1942 in which there was a government Handbook of Robotics (in 2058) which included the following three rules: A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm. A robot must obey orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law. A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

Etzioni’s Updated Rules

Etzioni has updated those three rules in his NY Times op-ed piece to:

Etzioni has updated those three rules in his NY Times op-ed piece to:

- An A.I. system must be subject to the full gamut of laws that apply to its human operator.

- An A.I. system must clearly disclose that it is not human.

- An A.I. system cannot retain or disclose confidential information without explicit approval from the source of that information.

Etzioni offered these updates to begin a discussion that would lead to a non-fictional Handbook of Robotics by the United Nations — and sooner than the 2058 sci-fi date. One that would regulate but not thwart the already growing global AI business.

And growing it is!

China’s Artificial Intelligence Manifesto

China has recently announced their long-term goal to become #1 in A.I. by 2030. They plan to grow their A.I. industry to over $22 billion by 2020, $59 billion by 2025 and $150 billion by 2030. They did this same type of long-term strategic planning for robotics – to make it an in-country industry and to transform the country from a low-cost labor source to a high-tech manufacturing resource… and it’s working.

China has recently announced their long-term goal to become #1 in A.I. by 2030. They plan to grow their A.I. industry to over $22 billion by 2020, $59 billion by 2025 and $150 billion by 2030. They did this same type of long-term strategic planning for robotics – to make it an in-country industry and to transform the country from a low-cost labor source to a high-tech manufacturing resource… and it’s working.

With this major strategic long-term AI push, China is looking to rival U.S. market leaders such as Alphabet/Google, Apple, Amazon, IBM and Microsoft. China is keen not to be left behind in a technology that is increasingly pivotal — from online commerce to self-driving vehicles to energy to consumer products. China aims to catch up by solving issues including a lack of high-end computer chips, software that writes software, and trained personnel. Beijing will play a big role in policy support and regulation as well as providing and funding research, incentives and tax credits.

Premature or not, the time is now

Many in AI and robotics feel that the present state of development in AI, including improvements in machine and deep learning methods, is primitive and decades away from independent thinking. Siri and Alexa, as fun and capable as they are, are still programmed by humans and cannot even initiate a conversation or truly understand its content. Nevertheless, there is a reason why people have expressed that they sense what may be possible in the future when artificial intelligence decides what ‘it’ thinks is best for us. Consequently, global regulation can’t hurt.

Leon Kuperman is the CTO of CUJO IoT Security. He co-founded ZENEDGE, an enterprise web application security platform, and Truition Inc. He is also the CTO of BIDZ.com.

Leon Kuperman is the CTO of CUJO IoT Security. He co-founded ZENEDGE, an enterprise web application security platform, and Truition Inc. He is also the CTO of BIDZ.com.