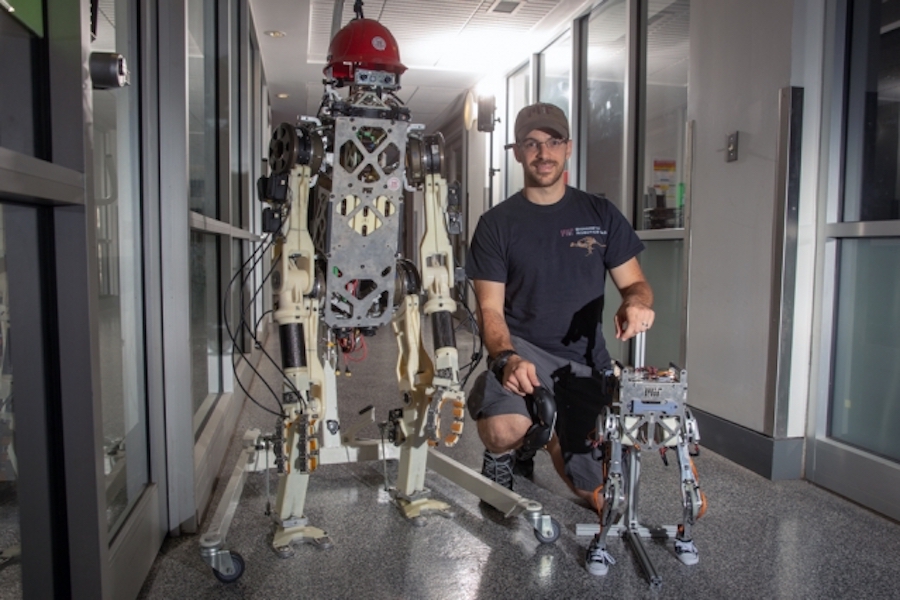

Photo: Tony Pulsone

By Jennifer Chu

Rescuing victims from a burning building, a chemical spill, or any disaster that is inaccessible to human responders could one day be a mission for resilient, adaptable robots. Imagine, for instance, rescue-bots that can bound through rubble on all fours, then rise up on two legs to push aside a heavy obstacle or break through a locked door.

Engineers are making strides on the design of four-legged robots and their ability to run, jump and even do backflips. But getting two-legged, humanoid robots to exert force or push against something without falling has been a significant stumbling block.

Now engineers at MIT and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign have developed a method to control balance in a two-legged, teleoperated robot — an essential step toward enabling a humanoid to carry out high-impact tasks in challenging environments.

The team’s robot, physically resembling a machined torso and two legs, is controlled remotely by a human operator wearing a vest that transmits information about the human’s motion and ground reaction forces to the robot.

Through the vest, the human operator can both direct the robot’s locomotion and feel the robot’s motions. If the robot is starting to tip over, the human feels a corresponding pull on the vest and can adjust in a way to rebalance both herself and, synchronously, the robot.

In experiments with the robot to test this new “balance feedback” approach, the researchers were able to remotely maintain the robot’s balance as it jumped and walked in place in sync with its human operator.

“It’s like running with a heavy backpack — you can feel how the dynamics of the backpack move around you, and you can compensate properly,” says Joao Ramos, who developed the approach as an MIT postdoc. “Now if you want to open a heavy door, the human can command the robot to throw its body at the door and push it open, without losing balance.”

Ramos, who is now an assistant professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, has detailed the approach in a study appearing today in Science Robotics. His co-author on the study is Sangbae Kim, associate professor of mechanical engineering at MIT.

More than motion

Previously, Kim and Ramos built the two-legged robot HERMES (for Highly Efficient Robotic Mechanisms and Electromechanical System) and developed methods for it to mimic the motions of an operator via teleoperation, an approach that the researchers say comes with certain humanistic advantages.

“Because you have a person who can learn and adapt on the fly, a robot can perform motions that it’s never practiced before [via teleoperation],” Ramos says.

In demonstrations, HERMES has poured coffee into a cup, wielded an ax to chop wood, and handled an extinguisher to put out a fire.

All these tasks have involved the robot’s upper body and algorithms to match the robot’s limb positioning with that of its operator’s. HERMES was able to carry out high-impact motions because the robot was rooted in place. Balance, in these cases, was much simpler to maintain. If the robot were required to take any steps, however, it would have likely tipped over in attempting to mimic the operator’s motions.

“We realized in order to generate high forces or move heavy objects, just copying motions wouldn’t be enough, because the robot would fall easily,” Kim says. “We needed to copy the operator’s dynamic balance.”

Enter Little HERMES, a miniature version of HERMES that is about a third the size of an average human adult. The team engineered the robot as simply a torso and two legs, and designed the system specifically to test lower-body tasks, such as locomotion and balance. As with its full-body counterpart, Little HERMES is designed for teleoperation, with an operator suited up in a vest to control the robot’s actions.

For the robot to copy the operator’s balance rather than just their motions, the team had to first find a simple way to represent balance. Ramos eventually realized that balance could be stripped down to two main ingredients: a person’s center of mass and their center of pressure — basically, a point on the ground where a force equivalent to all supporting forces is exerted.

The location of the center of mass in relation to the center of pressure, Ramos found, relates directly to how balanced a person is at any given time. He also found that the position of these two ingredients could be physically represented as an inverted pendulum. Imagine swaying from side to side while staying rooted to the same spot. The effect is similar to the swaying of an upside-down pendulum, the top end representing a human’s center of mass (usually in the torso) and the bottom representing their center of pressure on the ground.

Heavy lifting

To define how center of mass relates to center of pressure, Ramos gathered human motion data, including measurements in the lab, where he swayed back and forth, walked in place, and jumped on a force plate that measured the forces he exerted on the ground, as the position of his feet and torso were recorded. He then condensed this data into measurements of the center of mass and the center of pressure, and developed a model to represent each in relation to the other, as an inverted pendulum.

He then developed a second model, similar to the model for human balance but scaled to the dimensions of the smaller, lighter robot, and he developed a control algorithm to link and enable feedback between the two models.

The researchers tested this balance feedback model, first on a simple inverted pendulum that they built in the lab, in the form of a beam about the same height as Little HERMES. They connected the beam to their teleoperation system, and it swayed back and forth along a track in response to an operator’s movements. As the operator swayed to one side, the beam did likewise — a movement that the operator could also feel through the vest. If the beam swayed too far, the operator, feeling the pull, could lean the other way to compensate, and keep the beam balanced.

The experiments showed that the new feedback model could work to maintain balance on the beam, so the researchers then tried the model on Little HERMES. They also developed an algorithm for the robot to automatically translate the simple model of balance to the forces that each of its feet would have to generate, to copy the operator’s feet.

In the lab, Ramos found that as he wore the vest, he could not only control the robot’s motions and balance, but he also could feel the robot’s movements. When the robot was struck with a hammer from various directions, Ramos felt the vest jerk in the direction the robot moved. Ramos instinctively resisted the tug, which the robot registered as a subtle shift in the center of mass in relation to center of pressure, which it in turn mimicked. The result was that the robot was able to keep from tipping over, even amidst repeated blows to its body.

Little HERMES also mimicked Ramos in other exercises, including running and jumping in place, and walking on uneven ground, all while maintaining its balance without the aid of tethers or supports.

“Balance feedback is a difficult thing to define because it’s something we do without thinking,” Kim says. “This is the first time balance feedback is properly defined for the dynamic actions. This will change how we control a teleoperated humanoid.”

Kim and Ramos will continue to work on developing a full-body humanoid with similar balance control, to one day be able to gallop through a disaster zone and rise up to push away barriers as part of rescue or salvage missions.

“Now we can do heavy door opening or lifting or throwing heavy objects, with proper balance communication,” Kim says.

This research was supported, in part, by Hon Hai Precision Industry Co. Ltd. and Naver Labs Corporation.