Image courtesy of the researchers.

By Anne Trafton

MIT engineers have designed tiny robots that can help drug-delivery nanoparticles push their way out of the bloodstream and into a tumor or another disease site. Like crafts in “Fantastic Voyage” — a 1960s science fiction film in which a submarine crew shrinks in size and roams a body to repair damaged cells — the robots swim through the bloodstream, creating a current that drags nanoparticles along with them.

The magnetic microrobots, inspired by bacterial propulsion, could help to overcome one of the biggest obstacles to delivering drugs with nanoparticles: getting the particles to exit blood vessels and accumulate in the right place.

“When you put nanomaterials in the bloodstream and target them to diseased tissue, the biggest barrier to that kind of payload getting into the tissue is the lining of the blood vessel,” says Sangeeta Bhatia, the John and Dorothy Wilson Professor of Health Sciences and Technology and Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, a member of MIT’s Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research and its Institute for Medical Engineering and Science, and the senior author of the study.

“Our idea was to see if you can use magnetism to create fluid forces that push nanoparticles into the tissue,” adds Simone Schuerle, a former MIT postdoc and lead author of the paper, which appears in the April 26 issue of Science Advances.

In the same study, the researchers also showed that they could achieve a similar effect using swarms of living bacteria that are naturally magnetic. Each of these approaches could be suited for different types of drug delivery, the researchers say.

Tiny robots

Schuerle, who is now an assistant professor at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH Zurich), first began working on tiny magnetic robots as a graduate student in Brad Nelson’s Multiscale Robotics Lab at ETH Zurich. When she came to Bhatia’s lab as a postdoc in 2014, she began investigating whether this kind of bot could help to make nanoparticle drug delivery more efficient.

In most cases, researchers target their nanoparticles to disease sites that are surrounded by “leaky” blood vessels, such as tumors. This makes it easier for the particles to get into the tissue, but the delivery process is still not as effective as it needs to be.

The MIT team decided to explore whether the forces generated by magnetic robots might offer a better way to push the particles out of the bloodstream and into the target site.

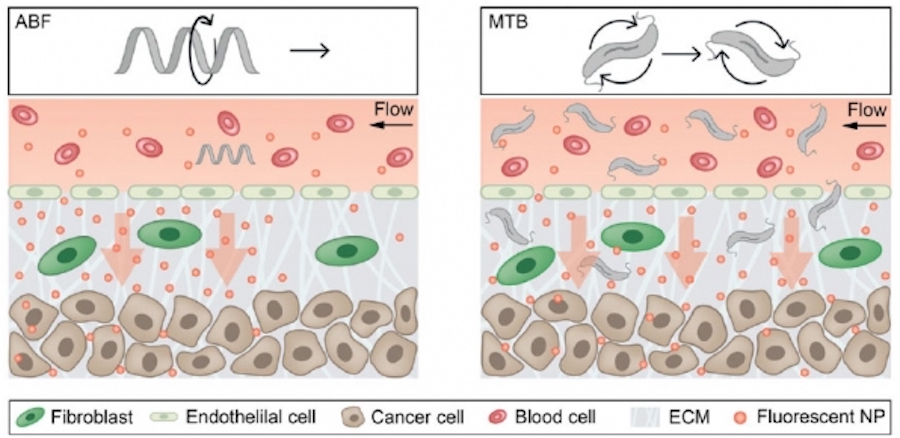

The robots that Schuerle used in this study are 35 hundredths of a millimeter long, similar in size to a single cell, and can be controlled by applying an external magnetic field. This bioinspired robot, which the researchers call an “artificial bacterial flagellum,” consists of a tiny helix that resembles the flagella that many bacteria use to propel themselves. These robots are 3-D-printed with a high-resolution 3-D printer and then coated with nickel, which makes them magnetic.

To test a single robot’s ability to control nearby nanoparticles, the researchers created a microfluidic system that mimics the blood vessels that surround tumors. The channel in their system, between 50 and 200 microns wide, is lined with a gel that has holes to simulate the broken blood vessels seen near tumors.

Using external magnets, the researchers applied magnetic fields to the robot, which makes the helix rotate and swim through the channel. Because fluid flows through the channel in the opposite direction, the robot remains stationary and creates a convection current, which pushes 200-nanometer polystyrene particles into the model tissue. These particles penetrated twice as far into the tissue as nanoparticles delivered without the aid of the magnetic robot.

This type of system could potentially be incorporated into stents, which are stationary and would be easy to target with an externally applied magnetic field. Such an approach could be useful for delivering drugs to help reduce inflammation at the site of the stent, Bhatia says.

Bacterial swarms

The researchers also developed a variant of this approach that relies on swarms of naturally magnetotactic bacteria instead of microrobots. Bhatia has previously developed bacteria that can be used to deliver cancer-fighting drugs and to diagnose cancer, exploiting bacteria’s natural tendency to accumulate at disease sites.

For this study, the researchers used a type of bacteria called Magnetospirillum magneticum, which naturally produces chains of iron oxide. These magnetic particles, known as magnetosomes, help bacteria orient themselves and find their preferred environments.

The researchers discovered that when they put these bacteria into the microfluidic system and applied rotating magnetic fields in certain orientations, the bacteria began to rotate in synchrony and move in the same direction, pulling along any nanoparticles that were nearby. In this case, the researchers found that nanoparticles were pushed into the model tissue three times faster than when the nanoparticles were delivered without any magnetic assistance.

This bacterial approach could be better suited for drug delivery in situations such as a tumor, where the swarm, controlled externally without the need for visual feedback, could generate fluidic forces in vessels throughout the tumor.

The particles that the researchers used in this study are big enough to carry large payloads, including the components required for the CRISPR genome-editing system, Bhatia says. She now plans to collaborate with Schuerle to further develop both of these magnetic approaches for testing in animal models.

The research was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation, the Branco Weiss Fellowship, the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.