Volatolomics: Robot noses may one day be able to ‘smell’ disease on your breath

Mimicking the function of Ruffini receptors using a bio-inspired artificial skin

Exploring the Design and Benefits of Modular Conveyor Systems

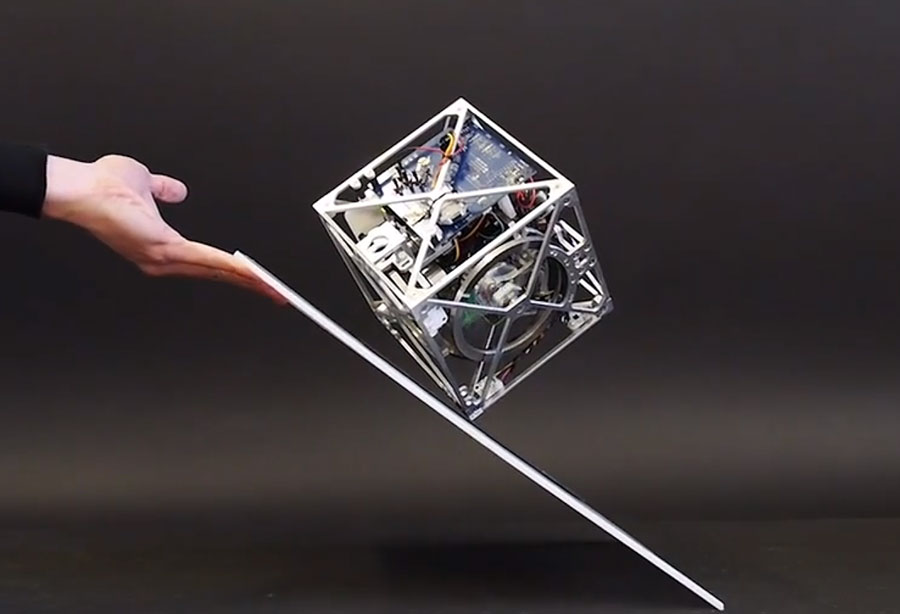

The one-wheel Cubli

Researchers Matthias Hofer, Michael Muehlebach and Raffaello D’Andrea have developed the one-wheel Cubli, a three-dimensional pendulum system that can balance on its pivot using a single reaction wheel. How is it possible to stabilize the two tilt angles of the system with only a single reaction wheel?

The key is to design the system such that the inertia in one direction is higher than in the other direction by attaching two masses far away from the center. As a consequence, the system moves faster in the direction with the lower inertia and slower in the direction with the higher inertia. The controller can leverage this property and stabilize both directions simultaneously.

This work was carried out at the Institute for Dynamic Systems and Control, ETH Zurich, Switzerland.

Almost a decade has passed since the first Cubli

The Cubli robot started with a simple idea: Can we build a 15cm sided cube that can jump up, balance on its corner, and walk across our desk using off-the-shelf motors, batteries, and electronic components? The educational article Cubli – A cube that can jump up, balance, and walk across your desk shows all the design principles and prototypes that led to the development of the robot.

Cubli, from ETH Zurich.

‘Fake’ data helps robots learn the ropes faster

Self-driving truck firm Waymo to deliver goods for Wayfair on Interstate 45

Robotic Welding Trends for 2022

Robot overcomes uncertainty to retrieve buried objects

A novel Kalman filter for target tracking in space

Open-source and open hardware autonomous quadrotor flies fast and avoids obstacles

Everything Under Control

At the forefront of building with biology

Ritu Raman, the d’Arbeloff Career Development Assistant Professor of Mechanical Engineering, focuses on building with biology, using living cells. Photo: David Sella

By Daniel de Wolff | MIT Industrial Liaison Program

It would seem that engineering is in Ritu Raman’s blood. Her mother is a chemical engineer, her father is a mechanical engineer, and her grandfather is a civil engineer. A common thread among her childhood experiences was witnessing firsthand the beneficial impact that engineering careers could have on communities. One of her earliest memories is watching her parents build communication towers to connect the rural villages of Kenya to the global infrastructure. She recalls the excitement she felt watching the emergence of a physical manifestation of innovation that would have a lasting positive impact on the community.

Raman is, as she puts it, “a mechanical engineer through and through.” She earned her BS, MS, and PhD in mechanical engineering. Her postdoc at MIT was funded by a L’Oréal USA for Women in Science Fellowship and a Ford Foundation Fellowship from the National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine.

Today, Ritu Raman leads the Raman Lab and is an assistant professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering. But Raman is not tied to traditional notions of what mechanical engineers should be building or the materials typically associated with the field. “As a mechanical engineer, I’ve pushed back against the idea that people in my field only build cars and rockets from metals, polymers, and ceramics. I’m interested in building with biology, with living cells,” she says.

Our machines, from our phones to our cars, are designed with very specific purposes. And they aren’t cheap. But a dropped phone or a crashed car could mean the end of it, or at the very least an expensive repair bill. For the most part, that isn’t the case with our bodies. Biological materials have an unparalleled ability to sense, process, and respond to their environment in real-time. “As humans, if we cut our skin or if we fall, we’re able to heal,” says Raman. “So, I started wondering, ‘Why aren’t engineers building with the materials that have these dynamically responsive capabilities?’”

These days, Raman is focused on building actuators (devices that provide movement) powered by neurons and skeletal muscle that can teach us more about how we move and how we navigate the world. Specifically, she’s creating millimeter-scale models of skeletal muscle controlled by the motor neurons that help us plan and execute movement as well as the sensory neurons that tell us how to respond to dynamic changes in our environment.

Eventually, her actuators may guide the way to building better robots. Today, even our most advanced robots are a far cry from being able to reproduce human motion — our ability to run, leap, pivot on a dime, and change direction. But bioengineered muscle made in Raman’s lab has the potential to create robots that are more dynamically responsive to their environments.