Learning challenges shape a mechanical engineer’s path

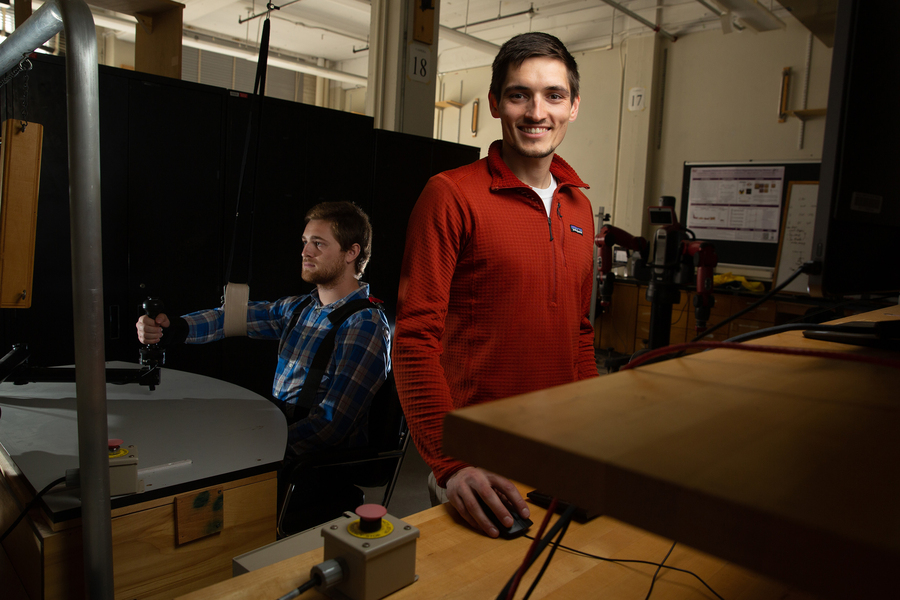

“I observed assistive technologies — developed by scientists and engineers my friends and I never met — which liberated us. My dream has always been to be one of those engineers.” Hermus says. Credit: Tony Pulsone

By Michaela Jarvis | Department of Mechanical Engineering

Before James Hermus started elementary school, he was a happy, curious kid who loved to learn. By the end of first grade, however, all that started to change, he says. As his schoolbooks became more advanced, Hermus could no longer memorize the words on each page, and pretend to be reading. He clearly knew the material the teacher presented in class; his teachers could not understand why he was unable to read and write his assignments. He was accused of being lazy and not trying hard enough.

Hermus was fortunate to have parents who sought out neuropsychology testing — which documented an enormous discrepancy between his native intelligence and his symbol decoding and phonemic awareness. Yet despite receiving a diagnosis of dyslexia, Hermus and his family encountered resistance at his school. According to Hermus, the school’s reading specialist did not “believe” in dyslexia, and, he says, the principal threatened his family with truancy charges when they took him out of school each day to attend tutoring.

Hermus’ school, like many across the country, was reluctant to provide accommodations for students with learning disabilities who were not two years behind in two subjects, Hermus says. For this reason, obtaining and maintaining accommodations, such as extended time and a reader, was a constant battle from first through 12th grade: Students who performed well lost their right to accommodations. Only through persistence and parental support did Hermus succeed in an educational system which he says all too often fails students with learning disabilities.

By the time Hermus was in high school, he had to become a strong self-advocate. In order to access advanced courses, he needed to be able to read more and faster, so he sought out adaptive technology — Kurzweil, a text-to-audio program. This, he says, was truly life-changing. At first, to use this program he had to disassemble textbooks, feed the pages through a scanner, and digitize them.

After working his way to the University of Wisconsin at Madison, Hermus found a research opportunity in medical physics and then later in biomechanics. Interestingly, the steep challenges that Hermus faced during his education had developed in him “the exact skill set that makes a successful researcher,” he says. “I had to be organized, advocate for myself, seek out help to solve problems that others had not seen before, and be excessively persistent.”

While working as a member of Professor Darryl Thelen’s Neuromuscular Biomechanics Lab at Madison, Hermus helped design and test a sensor for measuring tendon stress. He recognized his strengths in mechanical design. During this undergraduate research, he co-authored numerous journal and conference papers. These experiences and a desire to help people with physical disabilities propelled him to MIT.

“MIT is an incredible place. The people in MechE at MIT are extremely passionate and unassuming. I am not unusual at MIT,” Hermus says. Credit: Tony Pulsone

In September 2022, Hermus completed his PhD in mechanical engineering from MIT. He has been an author on seven papers in peer-reviewed journals, three as first author and four of them published when he was an undergraduate. He has won awards for his academics and for his mechanical engineering research and has served as a mentor and an advocate for disability awareness in several different contexts.

His work as a researcher stems directly from his personal experience, Hermus says. As a student in a special education classroom, “I observed assistive technologies — developed by scientists and engineers my friends and I never met — which liberated us. My dream has always been to be one of those engineers.”

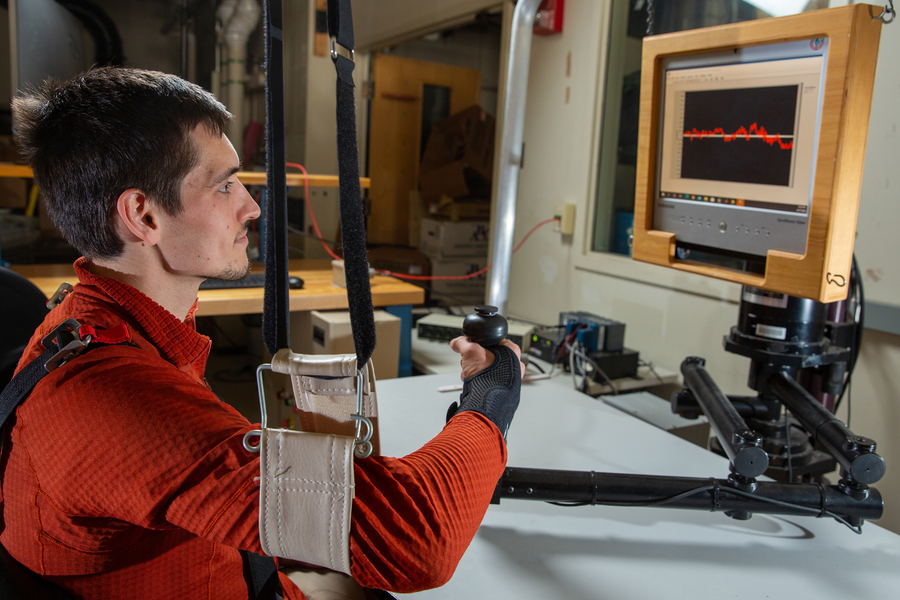

Hermus’ work aims to investigate and model human interaction with objects where both substantial motion and force are present. His research has demonstrated that the way humans perform such everyday actions as turning a steering wheel or opening a door is very different from much of robotics. He showed specific patterns exist in the behavior that provide insight into neural control. In 2020, Hermus was the first author on a paper on this topic, which was published in the Journal of Neurophysiology and later won first place in the MIT Mechanical Engineering Research Exhibition. Using this insight, Hermus and his colleagues implemented these strategies on a Kuka LBR iiwa robot to learn about how humans regulate their many degrees of freedom. This work was published in IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2022. More recently, Hermus has collaborated with researchers at the University of Pittsburgh to see if these ideas prove useful in the development of brain computer interfaces — using electrodes implanted in the brain to control a prosthetic robotic arm.

While the hardware of prosthetics and exoskeletons is advancing, Hermus says, there are daunting limitations to the field in the descriptive modeling of human physical behavior, especially during contact with objects. Without these descriptive models, developing generalizable implementations of prosthetics, exoskeletons, and rehabilitation robotics will prove challenging.

“We need competent descriptive models of human physical interaction,” he says.

While earning his master’s and doctoral degrees at MIT, Hermus worked with Neville Hogan, the Sun Jae Professor of Mechanical Engineering, in the Eric P. and Evelyn E. Newman Laboratory for Biomechanics and Human Rehabilitation. Hogan has high praise for the research Hermus has conducted over his six years in the Newman lab.

“James has done superb work for both his master’s and doctoral theses. He tackled a challenging problem and made excellent and timely progress towards its solution. He was a key member of my research group,” Hogan says. “James’ commitment to his research is unquestionably a reflection of his own experience.”

Following postdoctoral research at MIT, where he has also been a part-time lecturer, Hermus is now beginning postdoctoral work with Professor Aude Billard at EPFL in Switzerland, where he hopes to gain experience with learning and optimization methods to further his human motor control research.

Hermus’ enthusiasm for his research is palpable, and his zest for learning and life shines through despite the hurdles his dyslexia presented. He demonstrates a similar kind of excitement for ski-touring and rock-climbing with the MIT Outing Club, working at MakerWorkshop, and being a member of the MechE community.

“MIT is an incredible place. The people in MechE at MIT are extremely passionate and unassuming. I am not unusual at MIT,” he says. “Nearly every person I know well has a unique story with an unconventional path.”

Israeli firm deploys robots to speed up online shopping

End-of-Arm-Tooling powered by Stäubli Fluid Connectors

A bat-inspired framework to equip robots with sound-based localization and mapping capabilities

The Essential Role of Conveyors in Your Material Handling System

Q&A with Cortona3D

Researchers design a new efficient automated garage system

RoboHouse Interview Trilogy, part I: Christian Geckeler and the origami gripper

Part one of our RoboHouse Interview Trilogy: The Working Life of Robotics Engineers seeks out Christian Geckeler. Christian is a PhD student at the Environmental Robotics Lab of ETH Zürich. He speaks with Rens van Poppel about the experience of getting high into the wild.

What if drones could help place sensors in forests more easily? What if a sensor device could automatically grab and hold a tree branch? Which flexible material is also strong and biodegradable? These leaps of imagination lead Christian to a new kind of gripper, inspired by the Japanese art of folding.

His origami design wraps itself around tree branches close enough to trigger an unfolding movement. This invention may in the future improve our insight into hard-to-access forest canopies, in a way that is environmentally friendly and pleasant for human operators.

What is it like to work in the forest as a researcher with this technology?

“Robotic solutions deployed in forests are currently scarce,” says Christian. “So developing solutions for such an environment is challenging, but also rewarding. Personally I also enjoy being outdoors. Compared to a lab, the forest is wilder and more unpredictable. Which I find wonderful, except when it’s cold.”

Are there limits as to where the gripper can be deployed?

“The gripper is quite versatile. Rather than the type of trees, it is the diameter and angle of the branch that dictate whether the gripper can attach. Even so, dense foliage could hinder the drone, and there should be sufficient space for the gripper to attach.”

Are the used materials environmentally friendly?

“Currently not all components are biodegradable, and the gripper must be recollected after sampling is finished. However, we are currently working on a fully biodegradable gripper, which releases itself and falls on the ground after being exposed to sufficient amounts of water, which makes collection much easier.”

How good at outdoor living do aspiring tree-canopy researchers need to be?

“Everything is a learning process,” says Christian philosophically. “Rather than existing expertise, a willingness to learn and passion for the subject is much more important.”

What happens when the drone gets stuck in a tree?

“As a safety measure, the drone has a protective net on top which prevents leaves and branches from coming in contact with the propeller. And we avoid interaction between the drone and foliage, so this has never happened.”

What struck you when took the gripper into the wild?

“Perhaps the most surprising thing was the great variance that is found in nature; no two trees are alike and every branch is different. The only way of finding out if your solution works is by testing outside as soon and as often as possible.”

Christian ends with a note on the importance of social and technical interplay in robotics: “You may think you develop a robot perfectly, but you must make sure society actually wants it and that it is easy to use for not technically-minded people too.”

The post RoboHouse Interview Trilogy, Part I: Christian Geckeler and The Origami Gripper appeared first on RoboHouse.

Nimble autonomous robots help researchers explore the ocean, no ship required

North America Sees Record Robot Sales in 2022

Is the Built Industry Ready to Embrace Robotics in 2023?

Robot Talk Episode 36 – Interview with Ignazio Maria Viola

Claire chatted to Professor Ignazio Maria Viola from the University of Edinburgh all about aerodynamics, dandelion-inspired drones, and swarm sensing.

Ignazio Maria Viola is Professor of Fluid Mechanics and Bioinspired Engineering at the School of Engineering, University of Edinburgh, and Fellow of the Royal Institution of Naval Architects. He is the recipient of the ERC Consolidator Grant Dandidrone to explore the unsteady aerodynamics of dandelion-inspired drones.