Using AI to fight climate change

Using AI to fight climate change

Using AI to fight climate change

Ireland’s ‘RoboÉireann’ robot soccer team wins international RoboCup challenge shield

NVIDIA Brings Advanced Autonomy to Mobile Robots With Isaac AMR

Robot swarms neutralize harmful Byzantine robots using a blockchain-based token economy

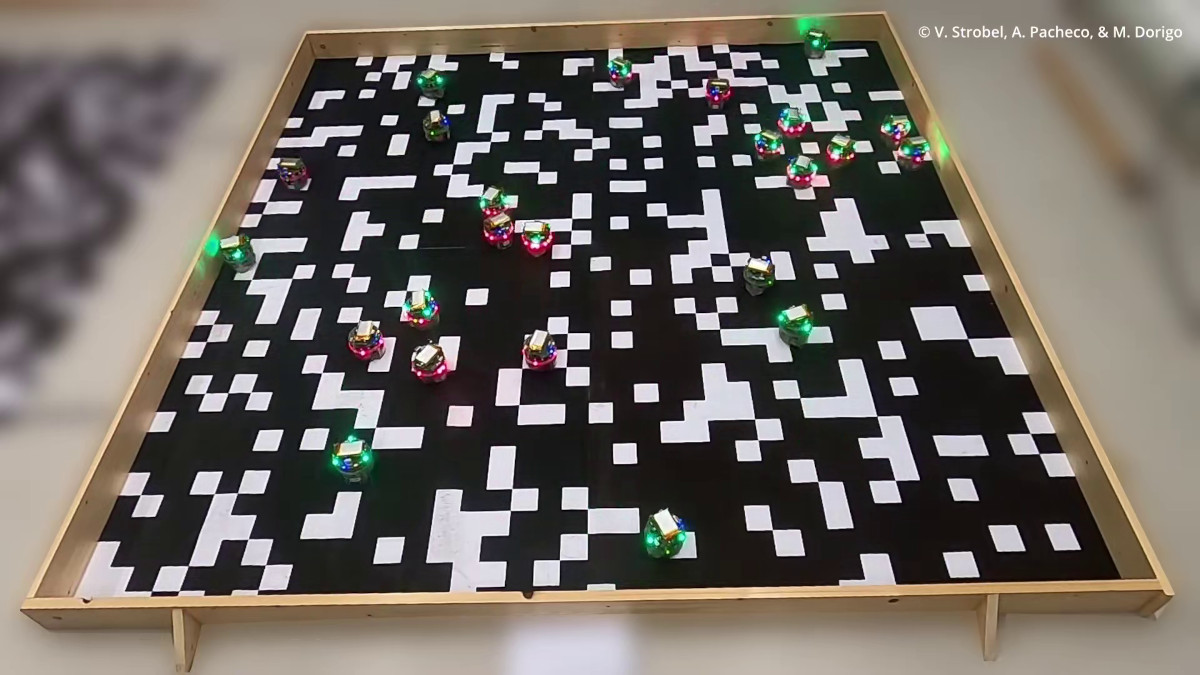

Dr. Volker Strobel, postdoctoral researcher; Prof. Marco Dorigo, research director of the F.R.S.-FNRS; and Alexandre Pacheco, doctoral student. The researchers from the Université Libre de Bruxelles, Belgium. Credit: IRIDIA, Université Libre de Bruxelles

In a new study, we demonstrate the potential of blockchain technology, known from cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin and Ethereum, to secure the coordination of robot swarms. In experiments conducted with both real and simulated robots, we show how blockchain technology enables a robot swarm to neutralize harmful robots without human intervention, thus enabling the deployment of autonomous and safe robot swarms.

Robot swarms are multi-robot systems that consist of many robots that collaborate in order to perform a task. They do not need a central control unit but the collective behavior of the swarm is rather a result of local interactions among robots. Thanks to this decentralization, robot swarms can work independently of external infrastructure, such as the Internet. This makes them particularly suitable for applications in a wide range of different environments such as underground, underwater, at sea, and in space.

Even though current swarm robotics applications are exclusively demonstrated in research environments, experts anticipate that in the non-distant future, robot swarms will support us in our everyday life. Robot swarms might perform environmental monitoring, underwater exploration, infrastructure inspection, and waste management—and thus make significant contributions to the transition into a fossil-free future with low pollution and high quality of life. In some of these activities, robot swarms will even outperform humans, leading to higher-quality results while ensuring our safety.

Once robot swarms are deployed in the real world, however, it is very likely that some robots in a swarm will break down (for example, due to harsh weather conditions) or might even be hacked. Such robots will not behave as intended and are called “Byzantine” robots. Recent research has shown that the actions of a very small minority of such Byzantine robots in a swarm can—similar to a virus—spread in the swarm and thus break down the whole system. Although security issues are crucial for the real-world deployment of robot swarms, security research in swarm robotics is lacking behind.

In Internet networks, Byzantine users such as hackers, have been successfully prevented from manipulating information by using blockchain technology. Blockchain technology is the technology behind Bitcoin: it enables users to agree on `who owns what’ without requiring a trusted third party such as a bank. Originally, blockchain technology was only meant to exchange units of a digital currency, such as Bitcoin. However, some years after Bitcoin’s release, blockchain-based smart contracts were introduced by the Ethereum framework: these smart contracts are programming code executed in a blockchain network. As no one can manipulate or stop this code, smart contracts enable “code is law”: contracts are automatically executed and do not need a trusted third party, such as a court, to be enforced.

So far, it was not clear whether large robot swarms could be controlled using blockchain and smart contracts. To address this open question, we presented a comprehensive study with both real and simulated robots in a collective-sensing scenario: the goal of the robot swarm is to provide an estimate of an environmental feature. To do so the robots need to sample the environment and then agree on the feature value. In our experiments, each robot is a member of a blockchain network maintained by the robots themselves. The robots send their estimates of environmental features to a smart contract that is shared by all the robots in the swarm. These estimates are aggregated by the smart contract that uses them to generate the requested estimate of the environmental feature. In this smart contract, we implemented economic mechanisms that ensure that good (non-Byzantine) robots are rewarded for sending useful information, whereas harmful Byzantine robots are penalized. The resulting robot economy prevents the Byzantine robots from participating in the swarm activities and influencing the swarm behavior.

Adding a blockchain to a robot swarm increases the robots’ computational requirements, such as CPU, RAM, and disk space usage. In fact, it was an open question whether running blockchain software on real robot swarms was possible at all. Our experiments have demonstrated that this is indeed possible as the computational requirements are manageable: the additional CPU, RAM, and disk space usage have a minor impact on the robot performance. This successful integration of blockchain technology into robot swarms paves the way for a wide range of secure robotic applications. To favor these future developments, we have released our software frameworks as open-source.