By Sonia Roberts, with additional editing by Dharini Dutia

Diligent Robotics, founded by Andrea Thomaz and Vivian Chu, develops socially intelligent automation solutions for hospitals. Moxi, their flagship robot, delivers items like medications and wound dressings between departments to save the clinical staff’s time. Diligent has just closed their Series B funding round with $30 million.

We sat down with Dr. Thomaz to talk about Moxi, how to manage people’s expectations about robots, and advice for young people and women in robotics. This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

Andrea Thomaz with Diligent’s flagship robot Moxi.

What kinds of problems are you trying to solve with Moxi?

We are building Moxi to help hospitals with the massive workforce shortage that they’re seeing now more than ever. We actually started the company with the same intention several years ago before there was a worldwide pandemic, and it really has just gotten to be an even bigger problem for hospitals. I feel really strongly that robots have a place to play in teamwork environments, and hospitals are a great example of that. There’s no one person’s job in a hospital that you would actually want to give over to automation or robots, but there are tiny little bits of a lot of people’s jobs that are absolutely able to be automated and that we can give over to delivery robots in particular like Moxi. [The main problem we’re trying to solve with Moxi is] point to point delivery, where we’re fetching and gathering things and taking them from one area of the hospital to another.

Hospitals have a lot of stuff that’s moving around every day. Every person in the hospital is going to have certain medications that need to be delivered to them, certain lab samples that need to be taken and delivered to the central lab, certain supplies that need to come up to them, food and nutrition every day. You have a lot of stuff that’s coming and going between patient units and all these different support departments.

Every one of these support departments has a process in place for getting the stuff moved around, but no matter what, there’s stuff that happens every single day that requires ad-hoc [deliveries] to happen between all of these departments and different nursing units. So sometimes that’s going to be a nurse that just needs to get something for their patient and they want that to happen as soon as possible. They’re trying to discharge their patient, they need a particular wound dressing kit, they’re going to run down and get it because they want to help their patient get out. Or if there’s something that needs to be hand carried because the regular rounding of medications has already happened, a lot of times you’ll have a pharmacy technician stop what they’re doing and go and run some infusion meds for a cancer patient, for example. It sort of falls between these departments. There’s different people that would be involved but a lot of times it does fall on the nursing units themselves. A nurse explained to us one time that nurses are the last line of defense in patient care.

Moxi performing a delivery for a clinical staff member.

What is changing with this most recent round of funding?

Over the last 6-12 months, the demand has really skyrocketed such that we’re barely keeping up with the demand for people wanting to implement robots in their hospitals. That’s the reason why we’re raising this round of funding, expanding the team, and expanding our ability to capitalize on that demand. A couple of years ago, if we were working with a hospital it was because they had some special funds set aside for innovation or they had a CTO or a CIO that had a background in robotics, but it certainly wasn’t the first thing that every hospital CIO was thinking about. Now that has completely changed. We’re getting cold outreach on our website from CIOs of hospitals saying “I need to develop a robotic strategy for our hospital and I want to learn about your solution.” Through the pandemic, I think everyone has seen that the workforce shortage in hospitals is only getting worse in the near term. Everybody wants to plan for the future and do everything they can to take small tasks off of the plates of their clinical teams. It’s been really exciting to be part of that market change and see that shift to where everybody is really really open to automation. Before we had to say “No no no, this is not the future, I promise it’s not scifi, I promise these really work.” Now [the climate has] really shifted to people understanding “This is actually something that can impact my teams.”

[Two of our investors are hospitals, and] that’s been one of our most exciting parts of this round. It’s always great to have a successful funding round, but to have strategic partners like Cedars-Sinai and Shannon Healthcare coming in and saying “Yeah, we actually want to build this alongside you” — it’s pretty exciting to have customers like that.

What kinds of technical problems did you run into when you were either building Moxi or deploying it in a hospital environment? How did you solve those problems?

One that was almost surprising in how often it came up, and really impacted our ability [to run Moxi in the hospital environment] because we have a software-based robotic solution that is connecting at a regular basis to cloud services, [was that] we had no clue how terrible hospital WiFi was going to be. We actually spent quite a while building in backup systems to be able to use WiFi, backup to LTE if we have to, but be smart about that so we’re not spending a whole bunch of money on LTE data. That was a problem that seemed very specific to hospitals in particular.

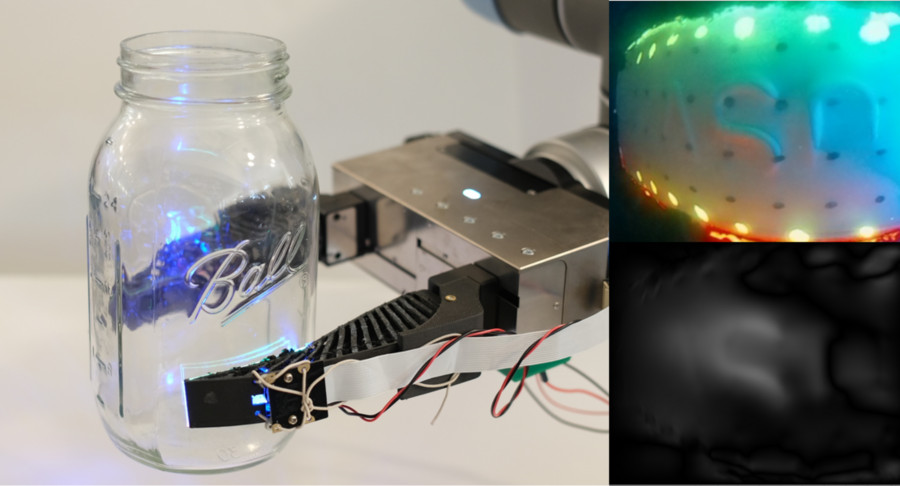

Another one was security and compliance. We just didn’t know what some of the different requirements were for hospitals until we actually got into the environments and started interacting with customers and understanding what they wanted to use Moxi for. When we were first doing research trials in 2018 or 2019, we had a version of the robot that was a little bit different than the one we have today. It had lots of open containers so you could just put whatever you wanted to on the robot and send it over to another location. We quickly learned that that limited what the robot was allowed to carry, because so much of what [the customers] wanted was to understand who pulled something out of the robot. So now we have an RF badge reader on the robot that is connected to locking storage containers that are only going to open if you’re the kind of person that is allowed to open the robot. That was an interesting technical challenge that we didn’t know about until after we got out there.

Moxi’s locking storage containers.

How did you work with nurses and the other healthcare professionals you were working with to figure out what would be the most helpful robot for them?

My background, and my co-founder Vivian Chu’s background, is in human-robot interaction so we knew that we didn’t know enough about nursing or the hospital environment. We spent the first 9 months of the company in 2018 building out our research prototype. It looked a lot like what Moxi looks like today. Under the hood it was completely different than what we have today in terms of the reliability and robustness of the hardware and software, but it was enough to get that platform out and have it deployed with nursing units. We embedded ourselves with four different nursing units across Texas over a year-long period. We would spend about 6-8 weeks with a nursing department, and we were just there — engineers, product people, and everybody in the company was cycling in and out a week or two at a time.

We would ask those nurses: “What would you actually want a robot like this to do?” Part of this that was really important was they didn’t have good ideas about what they would want the robot to do until they saw the robot. It was a very participatory design, where they had to see and get a sense for the robot before they would have good ideas of what they would want the robot to do. Then we would take those ideas [to the company] and come back and say “Yes we can do that,” or “No we can’t do that.” We came out of that whole process with a really great idea. We like to say that’s where we found our product market fit — that’s where we really understood that what was going to be most valuable for the robot to do was connecting the nursing units to these other departments. We can help a nurse with supply management and getting things from place to place within their department, or we can help them with things that are coming from really far away. [The second one] was actually impacting their time way way more.

Because the capabilities of robotic systems are usually misinterpreted, it can be really hard to manage the relationship with stakeholders and customers and set appropriate expectations. How did you manage that relationship?

We do a lot of demonstrations, but still with almost every single implementation you get questions about some robot in Hollywood, [and you have to say] “No, that’s the movies” and explain exactly what Moxi does.

From a design perspective, we also limit the English phrases that come out of Moxi’s mouth just because we don’t want to communicate a really high level of intelligence. There are lots of canned phrases and interactions on the iPad instead of via voice, and a lot of times the robot will just make meeps and beeps and flash lights and things like that.

Before starting the company, I had a lab, and one of the big research topics that we had for a number of years was embodied dialogue — how robots could have a real conversation with people. I had a very good appreciation for how hard that problem is, and also for just how much people want it. People come up to a robot, and they want it to be able to talk to them. How you can [set expectations] with the design and behavior of the robot has been a focus of mine since before we started the company. We purposefully don’t make the robot look very human-like because we don’t want there to be android human-level expectations, but [the robot does have a face and eyes so it can] communicate “I’m looking at that thing” and “I’m about to manipulate that thing,” which we think is important. It’s really about striking that balance.

What would you say is one lesson that you’ve learned from your work at Diligent so far and how are you looking to apply this lesson moving forward?

The difference between research and practice. On the one hand, the motivation and reason for starting a company is that you want to see the kinds of things that you’ve done in the research lab really make it out into the world and start to impact real people and their work. That’s been one of the most fascinating, impactful, and inspiring things about starting Diligent: Being able to go and see nurses when Moxi is doing work for them. They are so thankful! If you just hang back and watch Moxi come and do a delivery, almost always people are super excited to see the robot. They get their delivery and they’re like, “Oh, thank you Moxi!” That feels like we’re really making a difference in a way that you just don’t get with just research contributions that don’t make it all the way out into the world.

That being said though, there is a long tail of things that you have to solve from an engineering perspective beyond [developing a feature]. My VP of engineering Starr Corbin has this great way of putting it: The research team will get a certain thing on the product to be feature complete, where we’ve demonstrated that this feature works and it’s a good solution, but then there’s this whole phase that has to happen after that to get the feature to be production ready. I would say my biggest lesson is probably everything that it takes, and the entire team of people it takes, to get something from being feature complete to production ready. I have a deep appreciation for that. How fast we can move things out into the world is really dictated by some of that.

Andrea Thomaz (left) and Vivian Chu with Moxi.

What advice would you give young women in robotics?

If I put my professor hat on, I always had advice that I liked to give women in robotics, in academia, and just kind of pursuing things in general. Imposter syndrome is real, and everybody feels it. All you can do to combat it is not underestimate yourself. Speak up and know that you deserve a seat at the table. It’s all about hard work, but also making sure that your voice is heard. Some of the mentorship that I gave to a lot of my women grad students when I was a professor was around speaking engagements, speaking styles, and communication. It can be really uncomfortable when you’re the only anything in the room to stand up and feel like you deserve to be the one speaking, and so the more that you practice doing that, the more comfortable it can feel, the more confident you’ll feel in yourself and your voice. I think finding that confident voice is a really important skill that you have to develop early on in your career.

What’s one piece of advice you’ve received that you always turn to when things are tough?

There are two mentors that I’ve had who are women in AI and robotics. [In my] first year as a faculty member [the first mentor] came and gave a research seminar talk. I for some reason got to take her out to lunch by myself, so we had this amazing one-on-one. We talked a little bit about her talk, probably half of the lunch we talked about technical things, and then she just kind of turned the conversation [around] and said “Andrea, don’t forget to have a family.” Like, don’t forget to focus on that part of your life — it’s the most important thing. She got on a soapbox and said “You have to have a work life balance it’s so important. Don’t forget to focus on building a family for yourself, whatever that looks like.” That really stuck with me, especially as [when you’re] early in your career you’re worried about nothing but success. It was really powerful to have somebody strong and influential like that telling you “No, no, this is important and you need to focus on this.”

The other person that’s always been an inspiration and mentor for me that I’ll highlight [was the professor teaching a class I TA’d for at MIT]. I had found a bug in one of her homework problems, and she was like, “Oh, fascinating.” She was so excited that I had found a question that she didn’t know the answer to. She [just said], “Oh my gosh I don’t know, let’s go find out!” I remember her being this great professor at MIT, and she was excited to find something that she didn’t know and go and learn about it together as opposed to being embarrassed that she didn’t know something. I learned a lot from that interaction: That it’s fun to not know something because then you get to go and find the answer, and no matter who you are, you’re never expected to know everything.