Image: Computer History Museum

By Adam Conner-Simons | Rachel Gordon

Fernando “Corby” Corbató, an MIT professor emeritus whose work in the 1960s on time-sharing systems broke important ground in democratizing the use of computers, died on Friday, July 12, at his home in Newburyport, Massachusetts. He was 93.

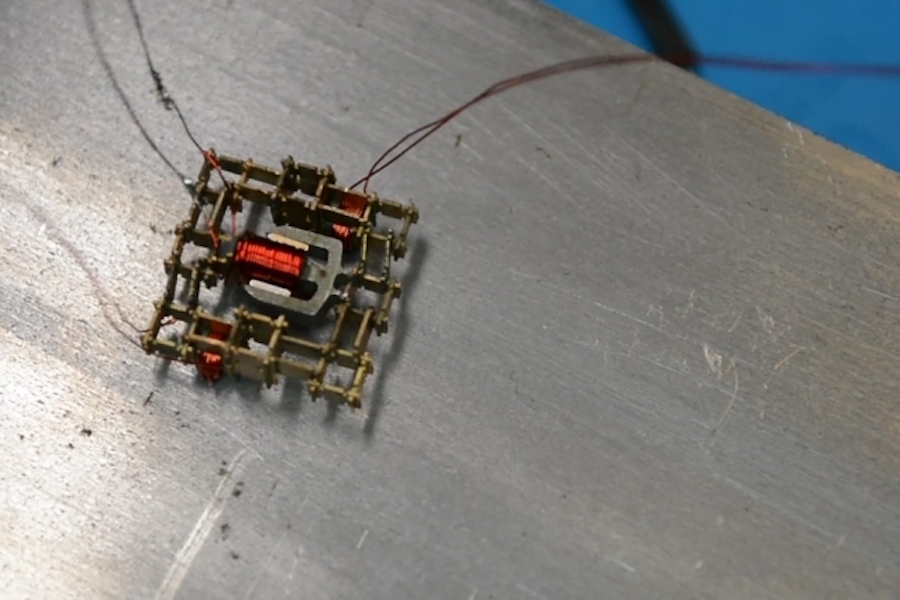

Decades before the existence of concepts like cybersecurity and the cloud, Corbató led the development of one of the world’s first operating systems. His “Compatible Time-Sharing System” (CTSS) allowed multiple people to use a computer at the same time, greatly increasing the speed at which programmers could work. It’s also widely credited as the first computer system to use passwords.

After CTSS Corbató led a time-sharing effort called Multics, which directly inspired operating systems like Linux and laid the foundation for many aspects of modern computing. Multics doubled as a fertile training ground for an emerging generation of programmers that included C programming language creator Dennis Ritchie, Unix developer Ken Thompson, and spreadsheet inventors Dan Bricklin and Bob Frankston.

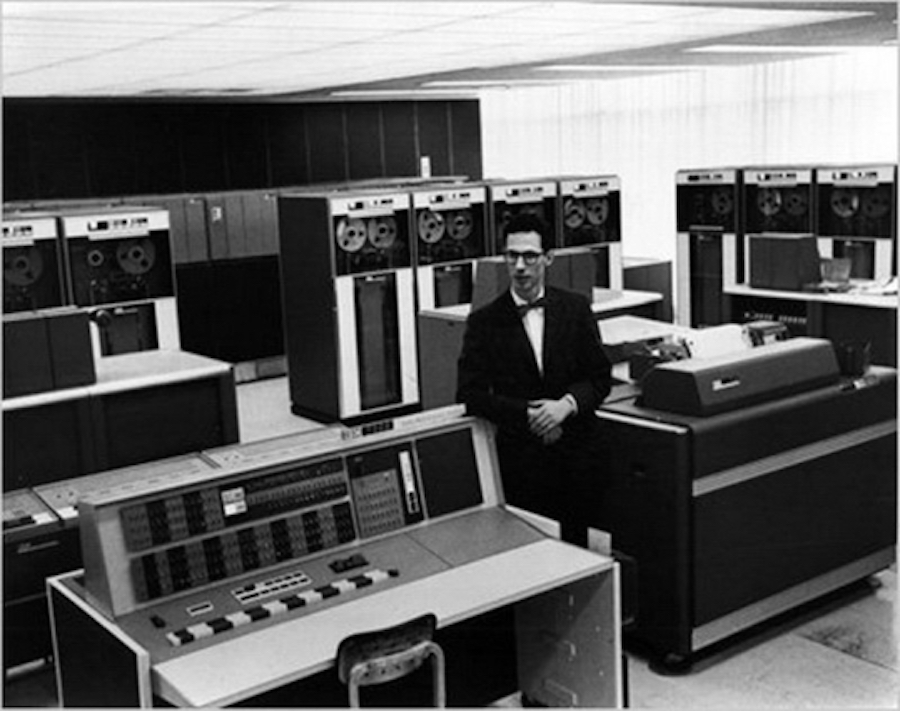

Before time-sharing, using a computer was tedious and required detailed knowledge. Users would create programs on cards and submit them in batches to an operator, who would enter them to be run one at a time over a series of hours. Minor errors would require repeating this sequence, often more than once.

But with CTSS, which was first demonstrated in 1961, answers came back in mere seconds, forever changing the model of program development. Decades before the PC revolution, Corbató and his colleagues also opened up communication between users with early versions of email, instant messaging, and word processing.

“Corby was one of the most important researchers for making computing available to many people for many purposes,” says long-time colleague Tom Van Vleck. “He saw that these concepts don’t just make things more efficient; they fundamentally change the way people use information.”

Besides making computing more efficient, CTSS also inadvertently helped establish the very concept of digital privacy itself. With different users wanting to keep their own files private, CTSS introduced the idea of having people create individual accounts with personal passwords. Corbató’s vision of making high-performance computers available to more people also foreshadowed trends in cloud computing, in which tech giants like Amazon and Microsoft rent out shared servers to companies around the world.

“Other people had proposed the idea of time-sharing before,” says Jerry Saltzer, who worked on CTSS with Corbató after starting out as his teaching assistant. “But what he brought to the table was the vision and the persistence to get it done.”

CTSS was also the spark that convinced MIT to launch “Project MAC,” the precursor to the Laboratory for Computer Science (LCS). LCS later merged with the Artificial Intelligence Lab to become MIT’s largest research lab, the Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL), which is now home to more than 600 researchers.

“It’s no overstatement to say that Corby’s work on time-sharing fundamentally transformed computers as we know them today,” says CSAIL Director Daniela Rus. “From PCs to smartphones, the digital revolution can directly trace its roots back to the work that he led at MIT nearly 60 years ago.”

In 1990 Corbató was honored for his work with the Association of Computing Machinery’s Turing Award, often described as “the Nobel Prize for computing.”

From sonar to CTSS

Corbató was born on July 1, 1926 in Oakland, California. At 17 he enlisted as a technician in the U.S. Navy, where he first got the engineering bug working on a range of radar and sonar systems. After World War II he earned his bachelor’s degree at Caltech before heading to MIT to complete a PhD in physics.

As a PhD student, Corbató met Professor Philip Morse, who recruited him to work with his team on Project Whirlwind, the first computer capable of real-time computation. After graduating, Corbató joined MIT’s Computation Center as a research assistant, soon moving up to become deputy director of the entire center.

It was there that he started thinking about ways to make computing more efficient. For all its innovation, Whirlwind was still a rather clunky machine. Researchers often had trouble getting much work done on it, since they had to take turns using it for half-hour chunks of time. (Corbató said that it had a habit of crashing every 20 minutes or so.)

Since computer input and output devices were much slower than the computer itself, in the late 1950s a scheme called multiprogramming was developed to allow a second program to run whenever the first program was waiting for some device to finish. Time-sharing built on this idea, allowing other programs to run while the first program was waiting for a human user to type a request, thus allowing the user to interact directly with the first program.

Saltzer says that Corbató pioneered a programming approach that would be described today as agile design.

“It’s a buzzword now, but back then it was just this iterative approach to coding that Corby encouraged and that seemed to work especially well,” he says.

In 1962 Corbató published a paper about CTSS that quickly became the talk of the slowly-growing computer science community. The following year MIT invited several hundred programmers to campus to try out the system, spurring a flurry of further research on time-sharing.

Foreshadowing future technological innovation, Corbató was amazed — and amused — by how quickly people got habituated to CTSS’ efficiency.

“Once a user gets accustomed to [immediate] computer response, delays of even a fraction of a minute are exasperatingly long,” he presciently wrote in his 1962 paper. “First indications are that programmers would readily use such a system if it were generally available.”

Multics, meanwhile, expanded on CTSS’ more ad hoc design with a hierarchical file system, better interfaces to email and instant messaging, and more precise privacy controls. Peter Neumann, who worked at Bell Labs when they were collaborating with MIT on Multics, says that its design prevented the possibility of many vulnerabilities that impact modern systems, like “buffer overflow” (which happens when a program tries to write data outside the computer’s short-term memory).

“Multics was so far ahead of the rest of the industry,” says Neumann. “It was intensely software-engineered, years before software engineering was even viewed as a discipline.”

In spearheading these time-sharing efforts, Corbató served as a soft-spoken but driven commander in chief — a logical thinker who led by example and had a distinctly systems-oriented view of the world.

“One thing I liked about working for Corby was that I knew he could do my job if he wanted to,” says Van Vleck. “His understanding of all the gory details of our work inspired intense devotion to Multics, all while still being a true gentleman to everyone on the team.”

Another legacy of the professor’s is “Corbató’s Law,” which states that the number of lines of code someone can write in a day is the same regardless of the language used. This maxim is often cited by programmers when arguing in favor of using higher-level languages.

Corbató was an active member of the MIT community, serving as associate department head for computer science and engineering from 1974 to 1978 and 1983 to 1993. He was a member of the National Academy of Engineering, and a fellow of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers and the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Corbató is survived by his wife, Emily Corbató, from Brooklyn, New York; his stepsons, David and Jason Gish; his brother, Charles; and his daughters, Carolyn and Nancy, from his marriage to his late wife Isabel; and five grandchildren.

In lieu of flowers, gifts may be made to MIT’s Fernando Corbató Fellowship Fund via Bonny Kellermann in the Memorial Gifts Office.

CSAIL will host an event to honor and celebrate Corbató in the coming months.

In this episode of

In this episode of