Canine companion insights help robots locate objects with an 89% success rate

Robot Talk Episode 148 – Ethical robot behaviour, with Alan Winfield

Claire chatted to Alan Winfield from the University of the West of England about developing new standards for ethics and transparency in robotics.

Alan Winfield is Professor of Robot Ethics at the University of the West of England (UWE), Visiting Professor at the University of York, and Associate Fellow of the Cambridge Centre for the Future of Intelligence. Alan co-founded the Bristol Robotics Laboratory, where his research is focussed on the science, engineering and ethics of cognitive robotics. Alan is an advocate for robot ethics; he chairs the advisory board of the Responsible Technology Institute at the University of Oxford and has co-drafted new standards on ethical risk assessment and transparency.

Mosrac – Efficient Motion Control Products Direct Drive PMSM & Encoders

Scaling Industrial Robots in the Age of AI

Scientists built the hardest AI test ever and the results are surprising

AI search robot uses 3D maps and internet knowledge to find lost items

Build enterprise-ready Agentic AI with DataRobot using NVIDIA Nemotron 3 Super

With the arrival of NVIDIA Nemotron 3 Super, organizations now have access to a high-accuracy reasoning model purpose-built for collaborative, multi-agent enterprise workloads. Being fully open, Nemotron 3 Super can be customized and deployed securely anywhere. However, having a powerful large language model (LLM) like Nemotron 3 Super is just the starting line. The real challenge is turning that powerful reasoning engine quickly into a production-grade system that your enterprise can trust for building AI agents and applications seamlessly using the LLM.

That is where DataRobot comes in. In this post, we will walk through how DataRobot’s Agent Workforce Platform, co-engineered with NVIDIA, makes it straightforward and quick to take Nemotron 3 Super from a standalone Large Language Model (LLM) to a fully deployed, evaluated, monitored, and governed production system that enterprises can trust and use to build their AI agents and applications seamlessly. We will also explore why mastering each of these steps is critical to successfully deploying specialized agentic AI systems.

A great LLM alone isn’t enough

Nemotron 3 Super is a highly capable 120-billion-parameter hybrid Mamba-Transformer MoE model, optimized for enterprise multi-agent tasks like IT automation and supply chain orchestration, boasting a 1-million-token context window. However, the move from pilot to reliable production is challenging; MIT research shows 95% of GenAI pilots fail, not due to the model’s capabilities, but due to issues in the surrounding deployment infrastructure.

Before deploying any LLM for enterprise applications and agents, organizations must address five critical areas:

- Evaluation and Comparison: Thoroughly assess models based on behavioral metrics (accuracy, hallucination) and operational metrics (cost, latency). Use LLMs as judges, proprietary, standard, or synthetic datasets, and comparative evaluations, often augmenting with human input.

- Efficient Hosting/Inferencing: Implement scalable, reliable, and elastic hosting infrastructure to ensure continuity for the LLM at the core of Generative and Agentic AI systems.

- Observability: Continuously monitor the deployed model’s behavior, both standalone and within agents, with instrumentation to detect and alert on drifts from desired performance.

- Real-Time Intervention and Moderation: Establish strong guardrails for real-time intervention to prevent undesirable or toxic behavior, such as PII leakage, which could compound quickly across interactions.

- Governance, Security, and Compliance: Enforce rigorous governance via authentication, authorization, approval workflows for updates, and comprehensive testing and reporting against enterprise, industry, and regulatory compliance standards.

DataRobot’s Agent Workforce Platform, co-engineered with NVIDIA, provides a unified solution for all these challenges with NVIDIA Nemotron 3 Super.

Launch Nemotron 3 Super NIM on your infrastructure with a few clicks

Your AI team wants Nemotron 3 Super in production. Your security team wants hardened containers with signed images. Your compliance team wants an audit trail from day one. And you want all of this to run without a month of configuration and a stack of support tickets.

NVIDIA NIM microservices are available directly within the DataRobot platform, pre-configured and optimized for NVIDIA AI Infrastructure. For Nemotron 3 Super — which uses NVFP4 quantization to deliver high performance while keeping compute costs predictable — this means your deployment comes production-ready out of the box. No inference engine tuning. No GPU parameter research. No guesswork.

Here’s what the workflow looks like:

- Browse and select. Open the NVIDIA NIM model gallery inside DataRobot. Each model comes with a clear description of its capabilities, supported GPU configurations, and resource requirements. Select Nemotron 3 Super and import it into your registry. DataRobot automatically tracks the version, tags it, and begins a full lineage record — so when your compliance team asks “which exact model version is running in production?”, the answer is already documented.

- Let the platform handle GPU sizing. DataRobot recommends the optimal GPU configuration for your deployment — whether you’re running on NVIDIA RTX PRO 6000 Blackwell Server Edition GPUs or other supported hardware — so you can focus on testing rather than troubleshooting infrastructure. You don’t need to understand the model’s internal architecture to get this right. The platform matches the model to your hardware and tells you what to provision. If your AI team later asks why you chose a particular configuration, the recommendation is logged and auditable.

- Deploy with one click. Select your configuration and deploy. Here’s what makes this different from downloading a model container and figuring out the rest yourself: DataRobot deploys the model with monitoring and access controls already wired in. There’s no separate step to “add observability later.” The moment your Nemotron 3 Super endpoint goes live, its already reporting health metrics, latency, throughput, and token consumption to your monitoring dashboard — giving you immediate visibility into how the deployment is performing.

Your AI team gets a live API endpoint they can start building immediately. You get a deployment that’s observable and auditable from minute one.

Multiple teams, one endpoint — without the free-for-all

Once Nemotron 3 Super is live, the next problem lands fast: multiple teams and applications all hitting the same deployment, with no way to prevent one team’s spike from degrading everyone else’s experience. Without controls, you’re back to fielding “why is the model so slow?” tickets.

DataRobot’s built-in quota management lets you set default access limits for each endpoint, then apply overrides for specific users, groups, or agents that need more (or less) capacity. Your production agent gets priority allocation; the experimentation team gets enough to stay productive without impacting production traffic. The platform enforces limits automatically — no more arbitrating access over email or diagnosing mystery slowdowns caused by a runaway agent on another team.

Built-in cost visibility

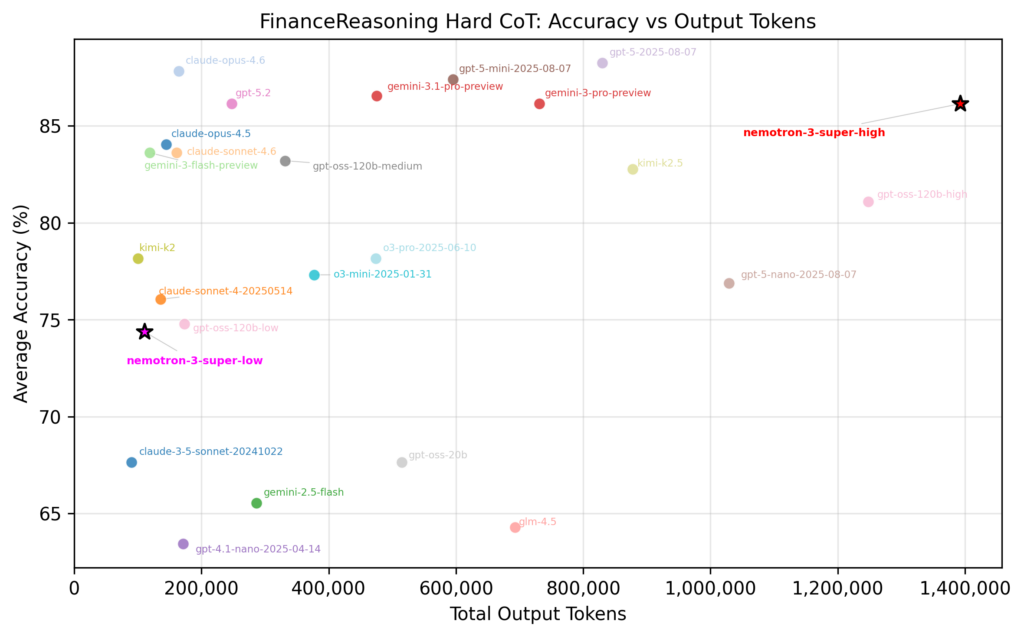

Not every task needs the same level of reasoning — and Nemotron 3 Super is equipped with a configurable thinking budget that lets you match inference cost to task complexity. The difference is dramatic: on the Finance Reasoning Hard benchmark, Nemotron 3 Super at its highest thinking budget reaches ~86% accuracy but consumes over 1.4 million output tokens, while the lowest thinking setting still delivers ~74% accuracy on roughly 100,000 tokens — a 14x reduction in token spend based on results conducted by DataRobot. For straightforward classification or routing tasks, the low setting is more than enough. For complex financial analysis or multi-step reasoning, you dial it up.

This means you can run a single model across multiple use cases and tune the cost-accuracy tradeoff per task, rather than deploying separate models for simple versus complex workloads. DataRobot surfaces this through its monitoring dashboard — giving you and your leadership clear visibility into token consumption per team, and per deployment. When your CFO asks “what are we spending on AI inference?”, you’ll have the numbers ready.

Rigorous evaluation before production

Deployment without evaluation is a recipe for failure. DataRobot provides comprehensive evaluation capabilities that let you rigorously test Nemotron 3 Super before they reach production.

LLM-as-a-Judge and out-of-the-box metrics

DataRobot’s evaluation framework spans the full range of metrics that matter:

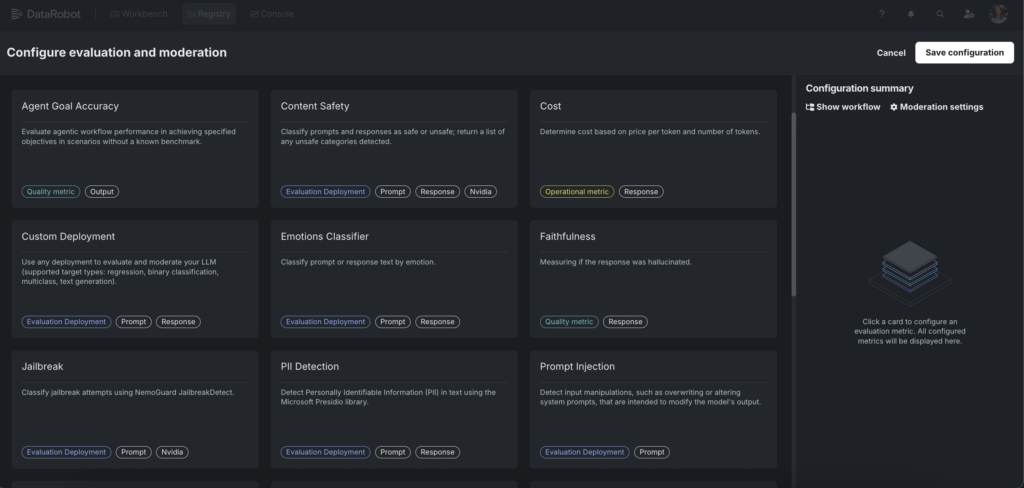

- Functional metrics and automated compliance tests measure correctness, faithfulness, relevance, bias, toxicity, etc., giving teams a rigorous, multi-dimensional view of model quality.

- Security and safety metrics provide real-time guards evaluating whether outputs comply with safety expectations — including detection of toxic language, PII exposure prevention, prompt-injection resistance, topic boundary adherence, and emotional tone classification.

- Economic metrics track token usage and cost, ensuring that your Nemotron 3 Super deployment remains economically sustainable at scale.

Playground comparison and the Evaluation API

DataRobot’s LLM Playground lets you setup side-by-side comparisons — running Nemotron 3 Super against other models, different prompt strategies, or alternative vector database configurations. You can configure up to three workflows at a time, run queries, and analyze results using LLM-as-a-judge alongside human-in-the-loop reviews with custom or synthetic test data.

For teams that want programmatic control, the Evaluation API supports the same full set of metrics, enabling automated evaluation pipelines that integrate with your existing CI/CD workflows.

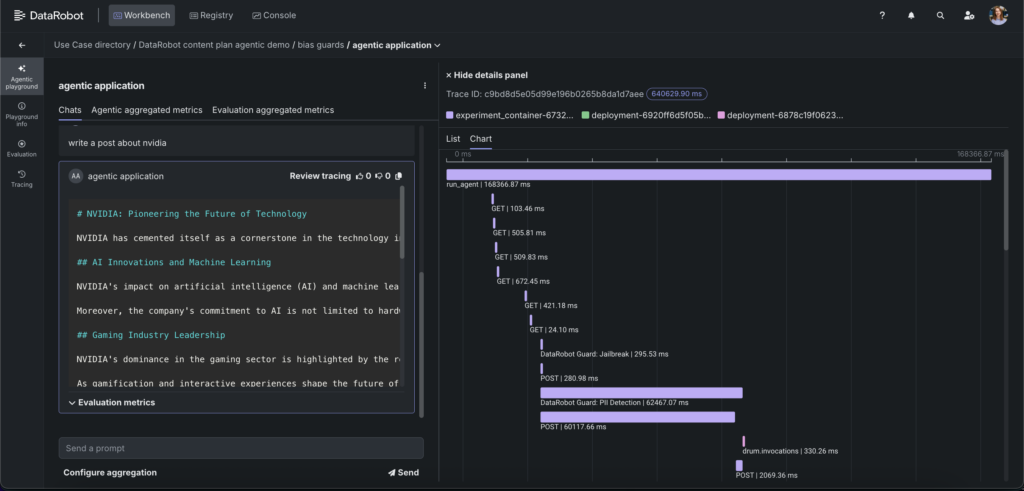

Execution tracing for deep debugging

Evaluation without explainability is incomplete. DataRobot’s tracing capabilities expose the full execution path of every interaction: the sequence and latency, the tools or functions invoked, and the inputs and outputs at each stage. This is especially important for Nemotron 3 Super powered agents because the model’s reasoning capabilities — including its configurable reasoning trace — mean that understanding how the agent arrived at a result is as important as whether the result was correct.

Tracing extends relevant metrics like accuracy and latency to both the input and output of each step, enabling you to pinpoint exactly where an issue originated in a multi-step workflow. This visibility makes debugging faster, iteration safer, and refinement more confident.

Scalable deployment and production monitoring

Once evaluation confirms Nemotron 3 Super is performing as expected, DataRobot ensures it stays that way in production.

Scalable infrastructure management

The Agent Workforce Platform handles the operational complexity of running Nemotron 3 Super at enterprise scale. With NVIDIA AI Enterprise natively embedded, the platform manages containerization, resource allocation, and scaling automatically. Whether you’re handling hundreds or thousands of concurrent requests, the infrastructure adapts — scaling GPU resources up and down based on demand without requiring manual intervention.

For organizations with strict data sovereignty requirements, this extends to on-premises and air-gapped deployments using the NVIDIA AI Factory for Government reference architecture.

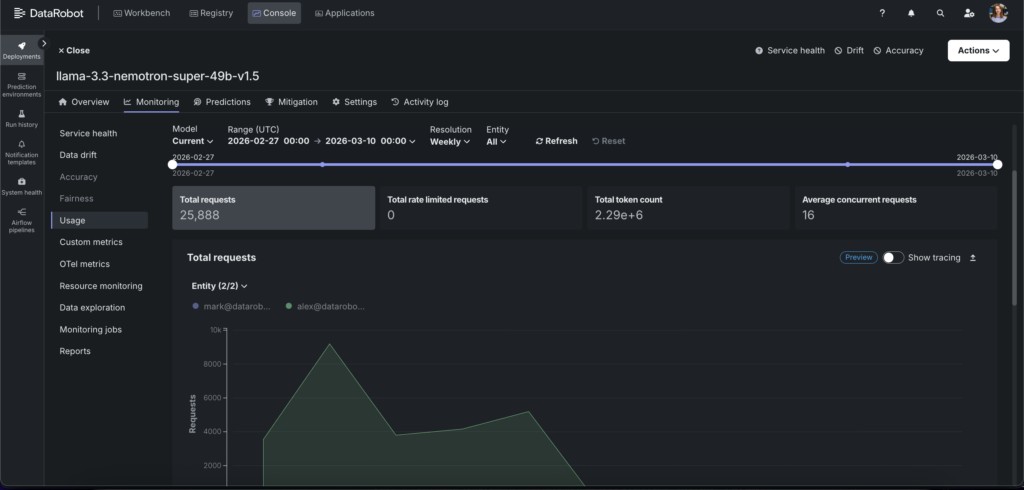

Continuous monitoring with out-of-the-box metrics

DataRobot’s observability framework delivers comprehensive visibility across health, quality, usage, and resource dimensions through a unified console:

- Real-time performance & resource tracking monitors latency, throughput, token consumption, CPU utilization, memory, and concurrency across every deployment — with quota rates and alerts to catch degradation and enforce cost governance before either impacts users.

- OTel tracing captures the full execution path of every system interaction — from initial prompt through each tool call, retrieval step, and model invocation — with timing and payload visibility at each node. Trace correlation links a quality degradation signal directly to the offending step, so root cause analysis takes minutes rather than hours.

- Custom alerting lets you define thresholds across any metric and route notifications to your preferred channels, enabling proactive intervention rather than reactive firefighting.

The monitoring system works seamlessly across all deployment environments, providing a single pane of glass whether your NVIDIA Nemotron 3 Super NIM are running in the cloud, on-premises, or in a hybrid configuration.

Enterprise governance and real-time intervention

Governance isn’t a checkbox at the end of a deployment — it’s an operational discipline that spans the entire model lifecycle. DataRobot provides governance capabilities across three critical dimensions for NVIDIA Nemotron 3 Super deployments.

Security risk governance

DataRobot enforces role-based access controls (RBAC) aligned with your organizational policies for all tools and enterprise systems that agents can access. This means your Nemotron 3 Super only interacts with the data and systems they’re explicitly authorized to use.

Robust, auditable approval workflows prevent unauthorized or unintended deployments and updates. Every change to the system — from prompt modifications to configuration updates — is tracked and requires appropriate authorization.

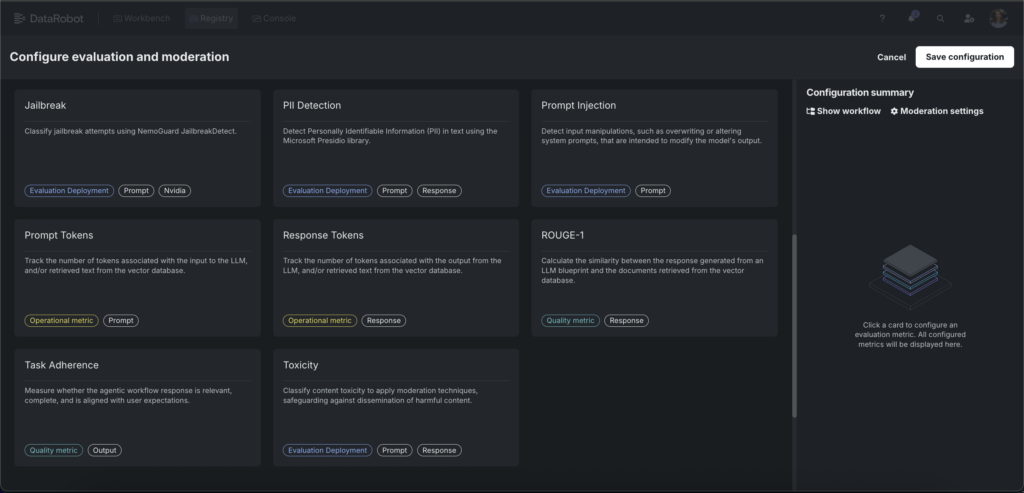

Operational risk governance with real-time intervention

This is where DataRobot’s capabilities become particularly critical. Beyond monitoring and alerting, the platform provides real-time moderation and intervention capabilities that can catch and address undesired inputs or outputs as they happen.

Multi-layer safety guardrails — including NVIDIA NeMo Guardrails for topic control, content safety, and jailbreak detection — operate in real time during model execution. You can configure these guardrails directly within the DataRobot Model Workshop, customizing thresholds and adding additional protections specific to NVIDIA Nemotron 3 Super deployment.

Lineage and versioning capabilities track all versions of NVIDIA Nemotron 3 – powered AI system: models, prompts, VDBs, datasets, creating an auditable record of how decisions were made and preventing behavioral drift across deployments.

Regulatory risk governance

DataRobot supports validation against applicable regulatory frameworks — including the EU AI Act, NIST RMF, and country- or state-level guidelines — identifying risks including bias, hallucinations, toxicity, prompt injection, and PII leakage.

Automated compliance documentation is generated as part of the deployment process, reducing audit effort and manual work while ensuring NVIDIA Nemotron 3 Super deployment maintains ongoing compliance as regulations evolve.

From model to impact

NVIDIA Nemotron 3 family of open models represents a significant step forward for enterprise agentic AI. Nemotron 3 Super, with its high-accuracy reasoning optimized for collaborative multi-agent workloads, is purpose-built for the kind of enterprise applications that drive real business outcomes.

But the organizations that will succeed with Nemotron 3 Super are not the ones with the most impressive demos. They’re the ones that rigorously evaluate behavior, monitor systems continuously in production, and embed governance across the entire agent lifecycle. Reliability, safety, and scale are not accidental outcomes — they are engineered through disciplined metrics, observability, and control.

DataRobot’s Agent Workforce Platform, co-engineered with NVIDIA, provides the complete foundation to make that happen. From one-click deployment to comprehensive evaluation, from continuous monitoring to real-time governance — we make the hard part of enterprise AI manageable.

Ready to build with NVIDIA Nemotron 3 Super on DataRobot? Request a demo and see how quickly you can move from model to production.

The post Build enterprise-ready Agentic AI with DataRobot using NVIDIA Nemotron 3 Super appeared first on DataRobot.

Robots that learn everyday tasks can free humans from repetitive work

A bicycle robot that can drive fast and jump over obstacles

Coding for underwater robotics

Screenshot from video showing underwater robotic vehicle. Credit: Tim Briggs/MIT Lincoln Laboratory.

Screenshot from video showing underwater robotic vehicle. Credit: Tim Briggs/MIT Lincoln Laboratory.

During a summer internship at MIT Lincoln Laboratory, Ivy Mahncke, an undergraduate student of robotics engineering at Olin College of Engineering, took a hands-on approach to testing algorithms for underwater navigation. She first discovered her love for working with underwater robotics as an intern at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in 2024. Drawn by the chance to tackle new problems and cutting-edge algorithm development, Mahncke began an internship with Lincoln Laboratory’s Advanced Undersea Systems and Technology Group in 2025.

Mahncke spent the summer developing and troubleshooting an algorithm that would help a human diver and robotic vehicle collaboratively navigate underwater. The lack of traditional localization aids — such as the Global Positioning System, or GPS — in an underwater environment posed challenges for navigation that Mahncke and her mentors sought to overcome. Her work in the laboratory culminated in field tests of the algorithm on an operational underwater vehicle. Accompanying group staff to field test sites in the Atlantic Ocean, Charles River, and Lake Superior, Mahncke had the opportunity see her software in action in the real world.

“One of the lead engineers on the project had split off to go do other work. And she said, ‘Here’s my laptop. Here are the things that you need to do. I trust you to go do them.’ And so I got to be out on the water as not just an extra pair of hands, but as one of the lead field testers,” Mahncke says. “I really felt that my supervisors saw me as the future generation of engineers, either at Lincoln Lab or just in the broader industry.”

Says Madeline Miller, Mahncke’s internship supervisor: “Ivy’s internship coincided with a rigorous series of field tests at the end of an ambitious program. We figuratively threw her right in the water, and she not only floated, but played an integral part in our program’s ability to hit several reach goals.”

Lincoln Laboratory’s summer research program runs from mid-May to August. Applications are now open.

Video by Tim Briggs/MIT Lincoln Laboratory | 2 minutes, 59 seconds