Photo: Gabriel Bousquet

By Jennifer Chu

MIT engineers have designed a robotic glider that can skim along the water’s surface, riding the wind like an albatross while also surfing the waves like a sailboat.

In regions of high wind, the robot is designed to stay aloft, much like its avian counterpart. Where there are calmer winds, the robot can dip a keel into the water to ride like a highly efficient sailboat instead.

The robotic system, which borrows from both nautical and biological designs, can cover a given distance using one-third as much wind as an albatross and traveling 10 times faster than a typical sailboat. The glider is also relatively lightweight, weighing about 6 pounds. The researchers hope that in the near future, such compact, speedy robotic water-skimmers may be deployed in teams to survey large swaths of the ocean.

“The oceans remain vastly undermonitored,” says Gabriel Bousquet, a former postdoc in MIT’s Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics, who led the design of the robot as part of his graduate thesis. “In particular, it’s very important to understand the Southern Ocean and how it is interacting with climate change. But it’s very hard to get there. We can now use the energy from the environment in an efficient way to do this long-distance travel, with a system that remains small-scale.”

Bousquet will present details of the robotic system this week at IEEE’s International Conference on Robotics and Automation, in Brisbane, Australia. His collaborators on the project are Jean-Jacques Slotine, professor of mechanical engineering and information sciences and of brain sciences; and Michael Triantafyllou, the Henry L. and Grace Doherty Professor in Ocean Science and Engineering.

The physics of speed

Last year, Bousquet, Slotine, and Triantafyllou published a study on the dynamics of albatross flight, in which they identified the mechanics that enable the tireless traveler to cover vast distances while expending minimal energy. The key to the bird’s marathon voyages is its ability to ride in and out of high- and low-speed layers of air.

Specifically, the researchers found the bird is able to perform a mechanical process called a “transfer of momentum,” in which it takes momentum from higher, faster layers of air, and by diving down transfers that momentum to lower, slower layers, propelling itself without having to continuously flap its wings.

Interestingly, Bousquet observed that the physics of albatross flight is very similar to that of sailboat travel. Both the albatross and the sailboat transfer momentum in order to keep moving. But in the case of the sailboat, that transfer occurs not between layers of air, but between the air and water.

“Sailboats take momentum from the wind with their sail, and inject it into the water by pushing back with their keel,” Bousquet explains. “That’s how energy is extracted for sailboats.”

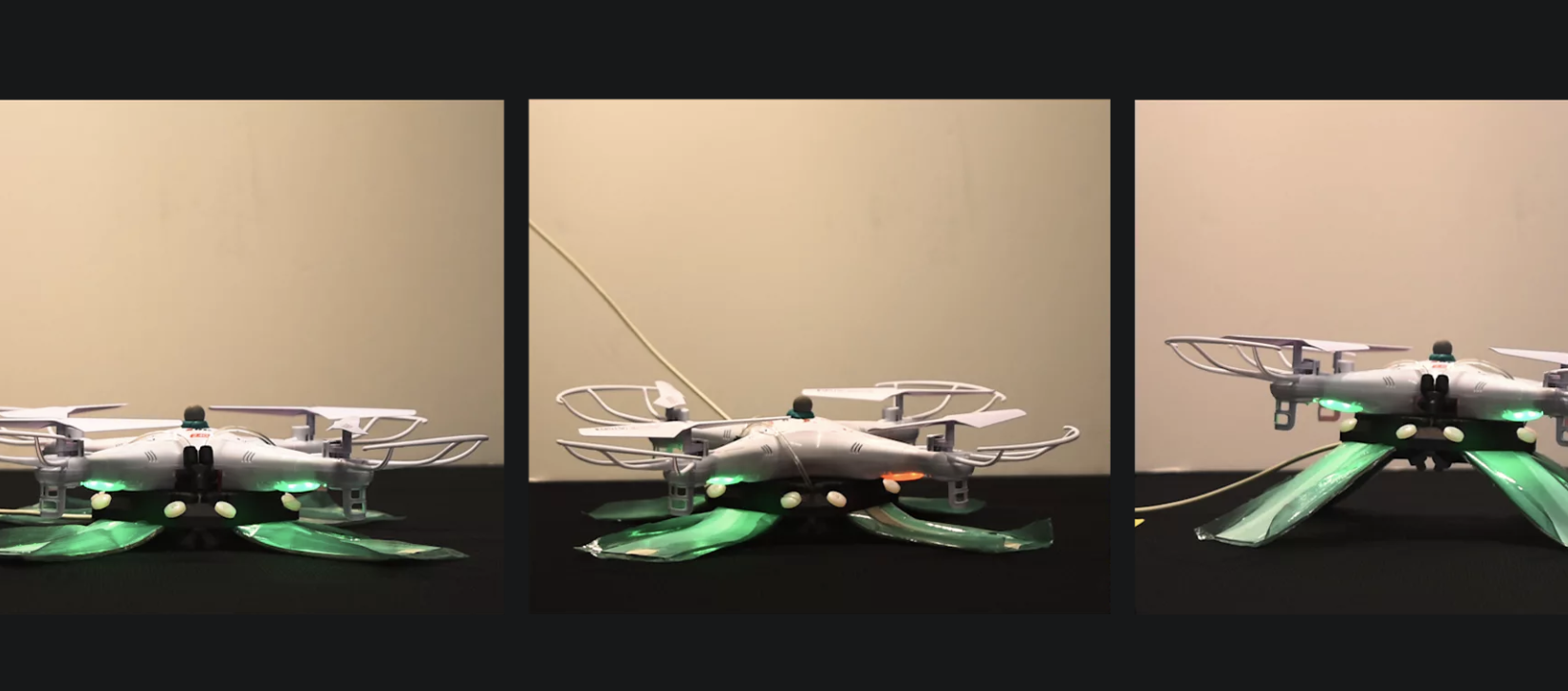

An albatross glider, designed by MIT engineers, skims the Charles River.

Bousquet also realized that the speed at which both an albatross and a sailboat can travel depends upon the same general equation, related to the transfer of momentum. Essentially, both the bird and the boat can travel faster if they can either stay aloft easily or interact with two layers, or mediums, of very different speeds.

The albatross does well with the former, as its wings provide natural lift, though it flies between air layers with a relatively small difference in windspeeds. Meanwhile, the sailboat excels at the latter, traveling between two mediums of very different speeds — air versus water — though its hull creates a lot of friction and prevents it from getting much speed. Bousquet wondered: What if a vehicle could be designed to perform well in both metrics, marrying the high-speed qualities of both the albatross and the sailboat?

“We thought, how could we take the best from both worlds?” Bousquet says.

Out on the water

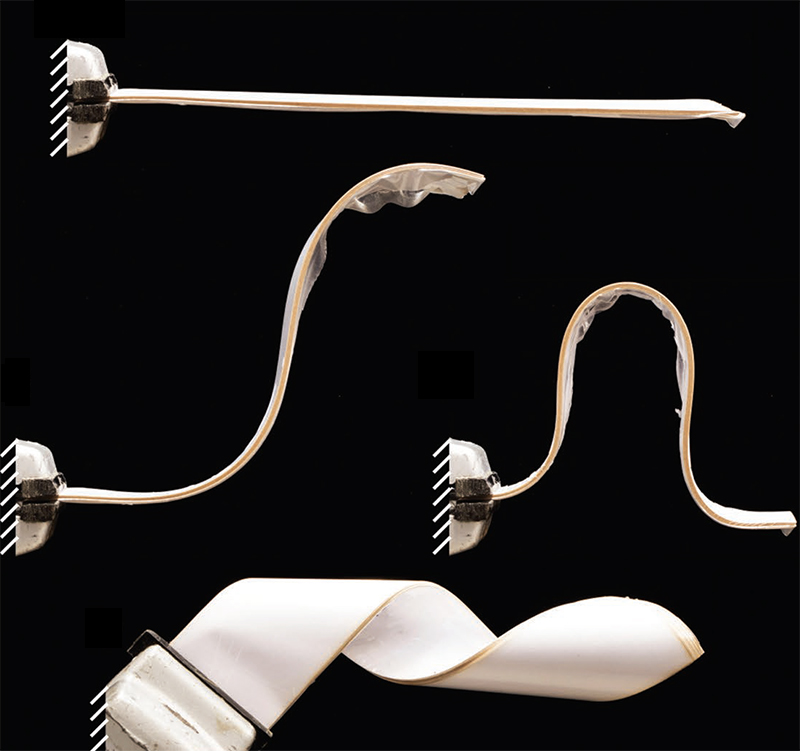

The team drafted a design for such a hybrid vehicle, which ultimately resembled an autonomous glider with a 3-meter wingspan, similar to that of a typical albatross. They added a tall, triangular sail, as well as a slender, wing-like keel. They then performed some mathematical modeling to predict how such a design would travel.

According to their calculations, the wind-powered vehicle would only need relatively calm winds of about 5 knots to zip across waters at a velocity of about 20 knots, or 23 miles per hour.

“We found that in light winds you can travel about three to 10 times faster than a traditional sailboat, and you need about half as much wind as an albatross, to reach 20 knots,” Bousquet says. “It’s very efficient, and you can travel very fast, even if there is not too much wind.”

The team built a prototype of their design, using a glider airframe designed by Mark Drela, professor of aeronautics and astronautics at MIT. To the bottom of the glider they added a keel, along with various instruments, such as GPS, inertial measurement sensors, auto-pilot instrumentation, and ultrasound, to track the height of the glider above the water.

“The goal here was to show we can control very precisely how high we are above the water, and that we can have the robot fly above the water, then down to where the keel can go under the water to generate a force, and the plane can still fly,” Bousquet says.

The researchers decided to test this “critical maneuver” — the act of transitioning between flying in the air and dipping the keel down to sail in the water. Accomplishing this move doesn’t necessarily require a sail, so Bousquet and his colleagues decided not to include one in order to simplify preliminary experiments.

In the fall of 2016, the team put its design to the test, launching the robot from the MIT Sailing Pavilion out onto the Charles River. As the robot lacked a sail and any mechanism to get it started, the team hung it from a fishing rod attached to a whaler boat. With this setup, the boat towed the robot along the river until it reached about 20 miles per hour, at which point the robot autonomously “took off,” riding the wind on its own.

Once it was flying autonomously, Bousquet used a remote control to give the robot a “down” command, prompting it to dip low enough to submerge its keel in the river. Next, he adjusted the direction of the keel, and observed that the robot was able to steer away from the boat as expected. He then gave a command for the robot to fly back up, lifting the keel out of the water.

“We were flying very close to the surface, and there was very little margin for error — everything had to be in place,” Bousquet says. “So it was very high stress, but very exciting.”

The experiments, he says, prove that the team’s conceptual device can travel successfully, powered by the wind and the water. Eventually, he envisions fleets of such vehicles autonomously and efficiently monitoring large expanses of the ocean.

“Imagine you could fly like an albatross when it’s really windy, and then when there’s not enough wind, the keel allows you to sail like a sailboat,” Bousquet says. “This dramatically expands the kinds of regions where you can go.”

This research was supported, in part, by the Link Ocean Instrumentation fellowship.

After the successful completion of the production of the material-optimised concrete façade mullions,

After the successful completion of the production of the material-optimised concrete façade mullions,